Wikipedia

This text was copied from Wikipedia on 12 January 2025 at 6:10AM.

| Four Days' Battle | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Anglo-Dutch War | |||||||

The Four Days Battle by Abraham Storck | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Kingdom of England Kingdom of England |

Dutch Republic Dutch Republic | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

79 ships of the line and frigates 21,000 men[2] |

84 ships of the line and frigates[3] 22,000 men[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

20 warships lost[4] 5,000 killed, wounded or captured[4] |

4 warships lost[3] 2,000 killed or wounded[4] | ||||||

The Four Days' Battle[a] was a naval engagement fought from 11 to 14 June 1666 (1–4 June O.S.) during the Second Anglo-Dutch War. It began off the Flemish coast and ended near the English coast, and remains one of the longest naval battles in history.

The Royal Navy suffered significant damage, losing around twenty ships in total. Casualties, including prisoners, exceeded 5,000 with over 1,000 men killed, including two vice-admirals, Sir Christopher Myngs and Sir William Berkeley. Almost 2,000 were taken prisoner including Vice-admiral George Ayscue.

Dutch losses were four ships destroyed by fire and over 2,000 men killed or wounded, among them Lieutenant Admiral Cornelis Evertsen, Vice Admiral Abraham van der Hulst and Rear Admiral Frederik Stachouwer. Although a clear Dutch victory, the surviving English ships were able to beat off an attempt to destroy them at anchor in the Thames estuary in early July. After quickly refitting, on 25 July the English defeated the Dutch in the St. James's Day Battle.

Background

Naval tactics

The introduction of sailing ships with a square rig, of a type later called the ship of the line, which were heavily armed with cannon, brought about a gradual change in naval tactics. Before and during the First Dutch War, fleet encounters were chaotic and consisted of individual ships or squadrons of one side attacking the other, firing from either side as opportunities arose but often relying on capturing enemy ships by boarding. Ships in each squadron were supposed to support those in the same squadron, particularly their flag officer, as their first priority. However, in the melee of battle, ships of the same squadron frequently blocked each other's fields of fire and collisions between them were not uncommon.[5]

Although Lieutenant-Admiral Maarten Tromp had formed a line against the Spanish fleet in 1639 in the action of 18 September 1639, this was not a planned formation but a desperate attempt to hold off a greatly superior, but badly organised, enemy. The initial sea battles of the First Dutch War were largely indecisive melees, but later in that war Robert Blake and George Monck issued instructions for each squadron to stay in line with its flag officer. At the Battle of Portland Tromp's attempt to overwhelm the English rear by concentrating his whole fleet against it and using his favourite tactic of boarding was frustrated by the English rear remaining in line ahead[6] at the Battle of the Gabbard, the English fleet in line ahead forced the Dutch into an artillery duel that defeated their more lightly armed ships with a loss of Dutch 17 ships sunk or captured.[7]

Between the first and second wars, the Dutch built the "New Navy", some sixty larger ships with heavier armament, about forty cannon, although the shallow waters around the Netherlands prevented them building ships as big as the largest English ones: additionally, English ships of the same size tended to have more and larger guns than their Dutch equivalents.[8] However, many of those the Dutch built were relatively small convoy escorts, frigates by English standards. It was intended to replace these by sixty heavier vessels but not all those planned had been completed or fitted out by the start of the war in 1665.[9] At the time of the Second Dutch War, the English fleet also had a signalling system which, if still rudimentary, was better than the Dutch reliance on standing instructions to fight in line. In the Battle of Lowestoft and the St. James's Day Battle, the English fighting in line ahead defeated the Dutch who did not.[10] De Ruyter favoured the tactic of concentrating his attack on a portion of the enemy's line, so achieving a breakthrough, and the capture of ships by boarding.[11] However, in the Four Days' Battle the Dutch generally fought in line, and the English fleet did not do so, at important stages in the fighting.[12]

From early in the 17th century, the Dutch navy had used fireships extensively, and in the First Anglo-Dutch War at the Battle of Scheveningen, Dutch fireships burned two English warships and an English fireship burned a Dutch warship. The Dutch in particular increased the number of their fireships after the outbreak of the Second Anglo-Dutch War but, at the Battle of Lowestoft, it was two English fireships that burned six Dutch warships which had collided and become entangled with one another. However, the limitations of fireships when used in open waters was demonstrated during the Four Days' Battle, where many were destroyed while trying to attack well-armed ships able to manoeuvre freely. The surrender of the English HMS Prince Royal when attacked by several Dutch fireships after it had run aground because of the panic this attack caused only demonstrated that fireships were useful against warships that were stationary or in confined harbours, but not those able to move in the open sea. However, this overall lack of success in this battle did not prevent both sides adding more fireships to their fleets.[13]

War in 1665

The Second Anglo-Dutch War arose from an escalation of existing commercial tensions between England and the Netherlands in 1664, involving English provocations in North America and West Africa.[14] Although negotiations to avoid the outbreak of war took place throughout much of 1664, both sides refused to compromise on what they considered were their vital interests in these two areas and in Asia, and hostile acts by each side continued despite diplomatic efforts to avoid war.[15] Louis XIV of France was intent on conquering the Spanish Netherlands and had signed a defensive treaty with the Dutch in 1662, with the intention of dissuading other countries from intervening if France invaded the Habsburg territories there.[16] The existence of this treaty strengthened the Dutch resolve not to make significant concessions, as Johan de Witt believed it would prevent England declaring war.[17] Charles II and his ministers hoped, firstly, to persuade Louis to repudiate the Dutch treaty and to replace it with an Anglo-French alliance, although such an arrangement would not assist Louis' plans for the Spanish Netherlands and, secondly, to strengthen English relations with Sweden and Denmark, both of which had significant fleets.[18] Although neither plan succeeded, Louis considered an Anglo-Dutch war unnecessary and likely to obstruct his plans to acquire Habsburg territory.,[19] Charles' ambassador in France reported the French opposed such a war and this gave Charles the hope that, if the Dutch could be provoked into declaring war, the French would evade their treaty obligations which only applied if the Dutch Republic were attacked, and refuse to be drawn into a naval war with England.[20] The war commenced with a declaration of war by the Dutch on 4 March 1665, following English attacks on two Dutch convoys off Cadiz and in the English Channel.[21]

De Witt also achieved the completion of many new warships, with twenty-one ordered during the early stages of the war to augment the existing fleet and sixty-four planned in 1664, including several large flotilla flagships comparable in armament to all but the largest English ones. These had been given greater constructional strength and a wider beam to support heavier guns. Although several of these ships had not been available to the Dutch fleet at the Battle of Lowestoft, they had been completed and fitted out after it.[22] The Dutch fleet had been confident of victory when it sought out and fought the English fleet in the Battle of Lowestoft in June 1665, but it suffered the worst Dutch defeat in any of the three Anglo-Dutch wars, with at least sixteen ships lost, and one-third of its personnel killed or captured. De Witt quickly saw that men were critical, not materiel: he sought to deal with the insubordination, lack of discipline and apparent cowardice among captains by executing three and exiling and dismissing others.[23][24] De Witt also turned to de Ruyter, rather than Cornelis Tromp who had previously been given temporary command, to lead the Dutch fleet because of his seniority and political neutrality: de Ruyter assumed command on 18 August 1665 and he transferred his flag to the newly commissioned Zeven Provinciën on 6 May 1666.[25]

Although the English had defeated the Dutch at Lowestoft, they failed to take full advantage of their victory. Despite the loss of ships and at least 5,000 men killed, wounded or captured, the escape of the bulk of the Dutch fleet frustrated the possibility of England ending the war with a single overwhelming victory.[26] In another reverse to English hopes of an early and successful end to the war, the rich Dutch Spice Fleet managed to return home safely after defeating an English flotilla that attacked it at the Battle of Vågen in August 1665. The Dutch navy was enormously expanded through the largest building programme in its history.[27] In August 1665 the English fleet was again challenged, though no large battles resulted. In 1666, the English became anxious to destroy the Dutch navy completely before it could grow too strong and were desperate to end the activity of Dutch raiders which threatened the collapse of English maritime trade.

After Lowestoft, English warships and privateers blockading the three main entry and exit points where Dutch merchant shipping concentrated, namely the Texel, the Maas river and off Zeeland temporarily paralysed Dutch overseas trade and weakened Dutch business confidence.[28] The existence of five admiralty colleges, each with its own policies on ship construction and armaments, each favouring its local commanders and with variable levels of efficiency, and the reluctance of Grand Pensionary Johan de Witt to appoint Orangist officers, all led to difficulty in creating a unified navy.[29]

At Lowestoft, the English Fleet was commanded by James, Duke of York, who was heir presumptive to his brother Charles II as well as Lord High Admiral of England. In view of the significant number of casualties among senior English officers and noble volunteers, including three killed next to the Duke, Charles insisted that his brother should no longer command at sea.[30] The command of the English fleet was therefore entrusted jointly to Prince Rupert, a cousin of Charles and James, and the Duke of Albemarle.[31]

French intervention

Louis had tried to act as mediator in July and August 1664 to prevent war being declared, but England did not accept his offer.[32] After Battle of Lowestoft, and concerned that the complete destruction of the Dutch fleet would leave the English fleet in a position to interfere with his plans in the Spanish Netherlands, Louis again offered mediation, but as he had already sent French troops into the Netherlands to assist the Dutch, and had also attempted to bring Denmark into an alliance with the Dutch Republic and France that was designed to put pressure on England, his credibility as mediator was undermined. In response to its rejection of his mediation, Louis XIV declared war on England on 16 January 1666.[33] The greater part of the French fleet was in the Mediterranean under the duc de Beaufort, and Louis intended that much of this would be brought into the Atlantic to join up with the Atlantic squadron commanded by Abraham Duquesne. The combined French fleet would then, it was intended, link up with the Dutch in the English Channel and the two would outnumber the English fleet.[34]

Louis' plans were based on the assumption that the Dutch fleet would be at sea in time to be able to prevent the English fleet attacking the weaker French fleet in the western English Channel. However, the Dutch could not undertake to be at sea to provide cover for Beaufort until 21 May. As a result, Beaufort, who left Toulon in April 1666 with 32 fighting ships, delayed at Lisbon for six weeks while the Four Days' Battle was fought.[35] Duquesne, who initially had 8 and later 12 ships, was ordered to join Beaufort at Lisbon so that the combined French fleet would be less vulnerable to a possible English attack before it could join the Dutch, although the two failed to meet and Duquesne returned to Brest while Beaufort stopped at Rochfort.[36]

Division of the fleet

The French intention to bring the bulk of their Mediterranean fleet to join the Dutch fleet at Dunkirk was known to Prince Rupert by 10 May and discussed by Charles and his Privy Council on 13 May. The next day, two privy councillors were delegated to discuss the matter with Albemarle. The delegates recorded that Albemarle would not object to detaching a squadron under Prince Rupert to block the Strait of Dover, provided he were left with at least 70 ships to fight the Dutch.[37] Rupert selected 20 generally fast or well-armed ships from the fleet and was instructed to collect any extra ships that might be available at Portsmouth or Plymouth.[38] Rupert's initial instructions were to attack Beaufort's fleet, whose original 32 ships included several weakly armed, poorly manned or slow vessels. However, once it was known that Duquesne's squadron was intended to join Beaufort, Rupert was instructed only to attack the French fleet if it was at anchor or was attempting an invasion, but otherwise to rejoin the main fleet as soon as he had encountered Beaufort or had credible information that the French fleet was not close enough to be a danger.[39] In the event the French fleet did not appear.

Although Albemarle has been accused either of the responsibility for dividing the fleet or complacency for accepting the loss of Rupert's squadron,[40] it is clear that he counted on having at least 70 ships to face the Dutch fleet, even after Rupert's squadron of 20 ships had been detached. When he spoke to the privy councillors on 14 May, the nominal strength of the fleet assigned to the joint commanders was over ninety, although at least a dozen of these had not joined the fleet at the mouth of the Thames and three ships then with the fleet later returned to port.[41] Four of the missing vessels had been refitted but could not be fully manned in time to join the fleet, three were being repaired and five newly constructed ships which had been expected to join in May were delayed by difficulties in manning and victualing them.[42] Much of the problem was that Charles II and his ministers had planned for a short war, but keeping a large fleet in being for a year after the partial victory of Lowestoft put demands on English public finances in 1666 that were almost impossible for it to meet.[43]

Albemarle became increasingly concerned about the small numbers of ships under his command at the mouth of the Thames as May progressed, particularly after he received intelligence that the Dutch fleet was preparing to leave its harbours.[44] He wrote three times between 26 and 28 May to the Navy Board and to Lord Arlington, one of Charles II's Secretaries of State. In each case, he reiterated his commitment to fight the Dutch fleet with 70 ships but, as he had only 54 ships on 27 May and 56 ships on 28 May, he requested a decision on whether he had to fight a much superior Dutch fleet or could retreat. His final letter, to Arlington, amounted to him asking for specific instructions to decline battle if this disparity in numbers persisted.[45]

The response from the Duke of York contained no instruction for Albemarle to decline battle if he had less than 70 ships, but left him discretion to make the decision. In part, this was because Charles and his ministers believed that the Dutch intended sail around the north of Scotland to join the French fleet before attacking the British fleet, so that Albemarle had time to increase the size of his fleet.[46] However, the intelligence relied on was faulty and, at the start of the battle the English fleet of 56 ships commanded by Albemarle was outnumbered by the 85 warships in the Dutch fleet commanded by Lieutenant-Admiral Michiel de Ruyter. Five ships joined Albemarle on 3 and 4 June, before the return of Rupert's squadron.[47]

On the day before the battle, the Dutch fleet comprised 72 large warships, 13 smaller warships classed as frigates, 9 fireships and an auxiliary force of 8 despatch yachts and twenty galleys, disposing of 4,200 guns and manned by 22,000 crewmen, constituting the largest and most powerful Dutch fleet up to that time.[48] De Ruyter had been informed that day by a Swedish merchant ship that it had seen the English fleet, which it estimated at 80 ships, off the Kentish coast two days before.[49]

Battle

First day, morning

Albemarle reorganised the squadrons of his fleet on account of the detachment of Rupert's ships and made the consequent changes in flag-officer appointments at a council of war in 30 May.[50] The next day, when the Dutch fleet was north of Nieuwpoort, de Ruyter also called his captains to his flagship to receive their final orders.[51] When the Dutch fleet anchored that evening, it was only 25 miles from the English fleet. On the morning of 1 June, both fleets set sail early and, around 7am, some Dutch ships were sighted by the English fleet. During the course of the morning it became clear to Albemarle that there were at least 80 Dutch warships: he consulted his flag-officers and they decided that, as it would be difficult to withdraw into the Thames estuary with the Dutch in close pursuit, they would have to fight.[52] However, as the high winds and rough sea were disadvantageous for fighting, they expected to do so only after the weather improved. Albemarle also sent a message to Rupert by the Kent to rejoin him if possible.[53]

The weather conditions in the morning had caused the Dutch fleet to anchor, and around noon Albemarle, realising that the Dutch fleet was at anchor and unprepared, decided to exploit the opportunity to attack the Dutch rear squadron under Lieutenant-Admiral Cornelis Tromp despite the adverse weather, in the hope it could be crippled before the Dutch centre and van could intervene.[54] The English fleet was not in regular battle order, but at 12.30 Albemarle ordered it to attack, with his red squadron and George Ayscue's white squadron mixed together in the lead and Thomas Teddiman's blue squadron forming the rear.[55] De Ruyter, who did not expect the English fleet would attack in wind and sea conditions in which many of its ships could not safely operate their lower gun batteries,[56] was taken completely by surprise by this attack, but Tromp who was closest to the English fleet ordered his ships to cut their cables, and they sailed to the south-east, followed by the rest of the Dutch fleet.[57]

The Dutch fleet had been anchored in a line running north east from Tromp in the rear to its van under Cornelis Evertsen the Elder, so only 30 or 40 ships of its rear under Tromp and some from its centre under de Ruyter could initially form a battle line against the whole English fleet.[58] As the English fleet held the weather gauge, it could have pressed an attack on the initially outnumbered Dutch but many English ships failed to come into close action. This failure, and Tromp's prompt action in getting his division underway, frustrated Albemarle's attempt to put Tromp's squadron out of action. After three hours during which neither side inflicted much damage in the other, Evertsen's squadron started to come into action and, by sailing through gaps in the English blue squadron or crossing its wake, gained the weather gauge against that part of the English fleet.[59]

First day, afternoon

By 5pm, the advantage of numbers had passed to the Dutch fleet, which was attacking the English blue squadron in the rear on both sides. Around this time, two Dutch ships caught fire, the Hof van Zeeland of Evertsen's squadron and the Duivenvoorde of Tromp's. Both were lost with most of their crews and two other Dutch ships had to deal with serious fires. Some survivors later claimed that these ships had been hit by "fiery bullets", and a type of ammunition consisting of hollow brass balls filled with a flammable substance did exist, however other Dutch eyewitnesses thought that flaming wads from the two ships' own guns, blown back by the strong wind, had caused the fires.[60]

As both fleets were heading for the shallow waters off the Flemish coast, and as his blue squadron was under heavy attack, Albemarle ordered ships of the red and white squadrons to wear to the northwest at around 5.30pm. Most of the red squadron saw the signal and wore in succession. The white squadron, with some red squadron ships in support, under Vice-Admiral Sir William Berkeley continued on a south-easterly course for another hour, as it had its own problems to deal with. By 6.30, Albemarle was leading the white squadron followed by the blue squadron northwest against Evertsen's squadron sailing southeast and engaged it at close range. De Ruyter's squadron facing no opponents, used the respite to make temporary repairs, and Albemarle and Evertsen's ships did the same after passing each other.[61]

To the southeast, Tromp's ship Liefde was in collision with Groot Hollandia, and both fell out of line. Vice-Admiral Sir William Berkeley saw this as an opportunity to redeem his reputation, damaged by accusations of cowardice at Lowestoft, and attacked with his own ship, HMS Swiftsure, with little support from other English ships[62] Immediately, Callantsoog and Reiger came to the rescue of their commander, destroying the rigging of the English ship with chain shot; the Reiger then managed to board the Swiftsure after first being repulsed. Berkeley was fatally wounded in the throat by a musket ball, after which the Swiftsure was captured. The ship's lieutenant was found in the powder room with his throat cut; it was claimed that he had tried to blow up the ship but, after his own crew had drenched the powder, he had cut his own throat rather than being taken prisoner.[63]

Two other ships from the white squadron shared the fate of the Swiftsure. The Loyal George had tried to assist the Swiftsure but was also captured and the damaged HMS Seven Oaks (the former Sevenwolden) was captured by the Beschermer The embalmed body of Berkeley, after being displayed in The Hague, was later returned to England under a truce, accompanied by a letter of the States General praising the Admiral for his courage. HMS Rainbow, one of the scouts who had first spotted the Dutch fleet, became isolated and fled to neutral Ostend, chased by twelve ships from Tromp's squadron.[64]

By 7pm, De Ruyter's squadron had completed its repairs and it advanced with the support of Evertsen and Tromp to attack Albemarle's ships, which had been reinforced by the white squadron. The reunited fleets twice engaged each other, with the Dutch fleet first sailing southeast then northwest, with the English fleet sailing in the opposite directions.[65] One English ship, the Henry, the flagship of Rear-Admiral Harman, was badly damaged losing two masts and left behind when the rest of Albemarle's fleet turned northwest. It was attacked by Dutch fireships after she had undertaken repairs and had tried to rejoin the fleet. The Henry managed to fight off three fireships although being set aflame and a third of her crew jumping overboard in panic. Harman refused an offer by Evertsen to surrender and a last shot at the Dutch ships barring the route to Albemarle cut Evertsen in two before Henry escaped to Aldborough.[66]

As the two fleets drew apart and anchored for the night around 10pm, the Dutch could feel satisfied with having survived the attempt to cripple Evertsen's squadron while at anchor or when it was outnumbered by the English fleet, and with having captured three English ships and forced three more out of the battle against a loss of two of their own to fire, although others on both sides were damaged and several Dutch ships had returned to port for repairs. The loss of Evertsen was also greatly mourned.[67] However, Tromp had failed to anchor at the same time as the main Dutch fleet, and his squadron consequently lost contact with de Ruyter.[68]

Second day, Albemarle's attack

The morning of 2 June was sunny and warm, with a light south-westerly breeze. At dawn, de Ruyter had only 53 warships under his direct command, as Tromp with twelve others had been separated when night fell. Tromp came into sight soon after dawn but was some miles astern of the rest of the fleet when fighting started. Another twelve Dutch ships had chased the Rainbow towards Ostend and were missing for most of the day, and others on both sides had returned to port for repairs, leaving de Ruyter and Tromp with 65 ships to face Albemarle's 48.[69]

Albemarle made the understandable mistake of believing that the significant reduction in the size of the Dutch fleet in sight was the result of English gunfire, and attempted to destroy the Dutch fleet by a direct attack starting at 6am, initially sailing south in the hope of isolating Tromp, then to the southeast, with the main Dutch fleet moving northwest. At about 7.30, the two fleets began fighting at close range as they passed each other.[70] During the morning, in light winds, the two fleets passed and re-passed several times, with ships from each side sometimes breaking through the other's line during these passes: Tromp able to join the rear of the Dutch line during this period.[71] Although the English fleet thought these were a reinforcement of new ships, about the same time Albemarle received a message that Rupert and his squadron were returning and would provide welcome assistance when they arrived[72]

The first two passes went badly for the English fleet, with HMS Anne, HMS Bristol and the hired Baltimore forced to return disabled to the Thames. After this, at about 10am, the wind died just as the two fleets had separated and they were becalmed for an hour.[73] When fighting resumed, de Ruyter in De Zeven Provinciën crossed the English line which was sailing to the southeast, and gained the weather gauge. His intention was to abandon line ahead tactics and to make an all-out attack on the English, boarding and capturing their ships, and had ordered the red flag to be raised, to signal this intention.[74][75]

Second day, Tromp's difficulties

Before he could attack the enemy line, it became apparent to de Ruyter that Tromp and seven or eight ships of the rear squadron had not gained the weather gauge and were now isolated to the leeward side of the English red squadron without support, and under attack from ships of that squadron under vice admiral Sir Joseph Jordan. It is unclear whether Tromp had not had seen De Ruyter's signal flags or had decided not to follow his orders, but within minutes six of his major ships, including his replacement flagship Provincie Utrecht had suffered major damage to their masts and were vulnerable to English fireships, which managed to burn his former flagship Liefde. The Spieghel, on which Vice-Admiral Abraham van der Hulst was killed by a musket shot, was attacked by three English ships of the red squadron and left disabled.[76]

However, the remainder of Tromp's ships were saved by de Ruyter who, with Vice Admiral Johan de Liefde, broke through the English blue squadron and drove off the English ships attacking Tromp while the rest of the Dutch fleet under Aert van Nes headed south, preventing the English blue squadron and the remainder of the red from joining Jordan in attacking Tromp. De Ruyter's careful planning, keeping the centre and rear of the English fleet occupied while he rescued Tromp was in contrast to Berkeley's impetuosity of the previous day.[77] However, he had taken a considerable risk, as George Ayscue, seeing the de Ruyter and Tromp in a vulnerable position, had turned his white squadron north to try to isolate them. Ayscue was criticised for not pressing the disordered Dutch more closely,[78] although his ships were also vulnerable to van Nes who had begun to turn north and could have joined de Ruyter quite quickly if the latter were attacked.[79]

Tromp, switching to his fourth ship already, then visited de Ruyter to thank him for the rescue but found him in a dark mood. De Ruyter had been forced to call off his plan for an all-out attack in the English fleet so that Tromp could be rescued, during which time Vice-Admiral van de Hulst and Rear-Admiral Frederick Stachouwer had both been killed. The list of ships leaving the Dutch fleet was growing: the Hollandia had been sent home together with the Gelderland, Delft, Reiger Asperen and Beschermer in order to guard the three captured English vessels. Now the damaged Pacificatie, Vrijheid, Provincie Utrecht and Calantsoog had also to return to port. The Spieghel had to be towed by the less damaged Vrede and, the damaged Maagd van Enkhuizen left next day for the Netherlands.[80]

De Ruyter's fleet, reduced by its losses to 57 effectives, re-formed its line to face 43 English ships, some hardly effective, and both fleets now passed each other three times on opposite tacks.[81] On the second pass De Zeven Provinciën lost its main topmast and De Ruyter withdrew from the fight to supervise repairs to his ship, delegating temporary command to Lieutenant-Admiral Aert van Nes. He was later accused of attempting to pass the responsibility for any defeat in the uncertain contest to van Nes, but there was no established rule at that time about when admirals should change ships: Albemarle had remained on the Royal Charles the previous day when it anchored to refit during the fighting without his conduct being questioned.[82] De Ruyter had strict detailed written orders from the States General to avoid unnecessary risks, to prevent a repeat of the events of the Battle of Lowestoft when the loss of the supreme commander had wrecked the Dutch command structure.

Van Nes commanded the Dutch fleet on its next three passes. As it held a leeward position, its guns had greater range which, with its superior numbers, made it clear by the early afternoon that the day's outcome could be decided by attrition.[83] Some English ships were dreadfully damaged, the merchantman Loyal Subject and another ship withdrew for their home ports and HMS Black Eagle (the former Dutch Groningen) raised the distress flag, but it sank from the many below-water shot holes it had suffered before any ships' boats could take off its crew. By 6pm, Albemarle's fleet, reduced to 41 ships still in action, was near to collapse, with many ships badly damaged and with significant casualties, and some with little powder and shot left.[84]

Second day, Dutch reinforcements

To add to the English troubles, in the late afternoon or early evening, a new Dutch contingent of twelve ships appeared on the southeast horizon. At the time, Albemarle believed that these were part of a fresh force, the English intelligence network in Holland having reported that the Dutch would retain a fourth squadron as a tactical reserve. Indeed, this option had been discussed but De Ruyter had just before the battle been convinced by the other admirals to use only three squadrons. In fact, the twelve were the ships of Tromp's squadron that had chased the Rainbow into Ostend in the first day and were now re-joining the fight. Although it was clear this reinforcement could not join the Dutch fleet before dark, there was no question of the English fleet continuing the battle for a third day with only 35 ships, besides six badly damaged ones, when Rupert's whereabouts were still unknown.[85]

Albemarle gave the order to retreat. Fortunately, the English fleet was heading northwest and had passed the Dutch fleet heading southeast, so no major change of course was necessary to take the fleet north of the Galloper Sand and into the deep water channel leading into the Thames[86] Van Nes had given the order for the Dutch fleet to tack in succession to begin another pass against their opponent before he realised that the English fleet were escaping. He decided not to rescind this order and replace it with one for all his ships to tack together, reversing the order of sailing, as this might cause confusion. This gave Albemarle a four or five mile head start, too much for the Dutch to overtake him before nightfall, as the sun had almost set and the wind was dying away. During his retreat, Albemarle placed 15 of his strongest and least damaged ships including his Royal Charles in line abreast as a rear-guard, and ordered the six most badly damaged to make their own way to port. The St Paul (the former Dutch Sint Paulus) had taken on too much water to keep with the other ships and was burned to prevent capture after its crew had been taken off.[87]

Both sides had missed chances to strike decisive blows on the second day. First, Albemarle's morning attack on the Dutch fleet, reduced by the absence of Tromp's squadron, had been unsuccessful. Then de Ruyter could not have felt entirely satisfied, as had later been unable to launch his desired all-out attack on the English fleet because he had to rescue Tromp.[88] Although this rescue prevented Tromp's ships being overwhelmed, it and the failure van Nes to reverse the Dutch fleet quickly, lost the Dutch the chance of capturing many damaged English ships. The outnumbered English fleet had fought well and, although clearly defeated and in retreat, it had not been annihilated. However, it had only 28 ships that could be repaired and refitted for further combat. During the night, the two fleets lay becalmed about five miles apart making repairs.[89]

Third day

A light breeze from the northeast replaced the overnight calm before sunrise, and the English fleet decided to continue its retreat, steering slightly north of west. Van Nes called a council of war, as de Ruyter was still far astern: this agreed to pursue the English fleet in line abreast and with the intention of engaging and overwhelming the English fleet, although it remained out of reach through the morning.[90] By midday the wind strengthened and became easterly, so the fastest Dutch ships were released to try to overtake the English fleet.[91] However, as the 15 ships of the English rearguard were all large and powerful, each with several large guns (32-pounder cannon) mounted in their sterns, whereas even the largest Dutch ships had only two medium-calibre guns that could fire forward, the English fleet was able to keep the Dutch ships at a distance, and continued on their way without difficulty.[92]

Shortly before 3pm, Rupert's squadron was sighted to the southwest by the leading English ships, heading north. When van Nes saw this, he tried to bring Albemarle's ships into action before Rupert's squadron could reinforce his fleet. Albemarle's pilots assumed that both his fleet and Rupert's squadron were already north of the Galloper Sand and, at about 5pm, they steered to the west to join Rupert. The leading English ships were small, and their shallow draught allowed them to pass over the Galloper Sand without difficulty, but HMS Royal Charles, HMS Royal Katherine and HMS Prince Royal grounded on the sandbank. The first two managed to get free quickly, but the larger Prince Royal, flagship of the white squadron, was stuck fast.[93] It was soon surrounded by several Dutch ships, including two fireships. Vice-Admiral George Ayscue wished to resist any Dutch attack and begged his men to stay calm and repulse the approaching fireships. However, the crew panicked and a certain Lambeth struck the flag, forcing Ayscue to surrender to Tromp on the Gouda, the only time in history an English admiral of so high a rank was captured at sea.[94] Tromp wished to keep the Prince Royal as a prize, and when de Ruyter finally caught up with his fleet at about 7pm, he initially raised no objection. However, when it floated as the tide rose, its rudder and steering were found to be damaged so it could not steer itself. As the recombined English fleet was preparing to attack, de Ruyter ordered the Prince Royal to be burned at once, as it was possible that an attempt would be made to recapture it.[95] De Ruyter had explicit written instructions from the States-General to burn prizes in such situations. Tromp did not dare to make any objections because he had already sent home some prizes against orders; but later he would freely express his discontent, still trying to get compensation for the loss of this valuable prize in 1681.

After Rupert had left the main fleet on 29 May, Albemarle received information that a Dutch fleet which significantly outnumbered his had left its ports and was at sea. When this was passed to the king and his advisers, they sent Rupert an order for his squadron to return on 31 May: this reached him off the Isle of Wight on 1 June. His squadron reached Dover on 2 June but was delayed by light winds and adverse tides until the next morning.[96]

Albemarle had only 27 ships remaining after the loss of the Prince Royal and sending six badly damaged ships to port. Rupert brought 26 ships, the 20 he had on 29 May together with Kent and Hampshire which had been detached from the fleet before 29 May and four fireships. Three more ships from the Thames, the Convertine, Sancta Maria and Centurion also joined the fleet at the same time as Rupert. The English fleet therefore consisted of 52 warships, nearly half of them undamaged and with full crews, and six fireships facing some 69 Dutch warships, 57 major ones and the rest frigates, and six or seven fireships.[97][98]

Soon after Rupert's arrival, Albemarle convened a council of war which agreed to resume the battle in the following day, despite being weaker than the Dutch.[99] Realising this, de Ruyter, who had resumed command from van Nes took his fleet eastward to make repairs and prepare for a fourth day of combat.[100] De Ruyter considered that, despite the casualties suffered by many of his ships and shortages of ammunition, his superiority in numbers could still be decisive.[101]

Albemarle and Rupert reorganised the English fleet. Rupert's squadron of undamaged fast ships with fresh crews took the van as the new white squadron under his own command, with Sir Christopher Myngs and Sir Edward Spragge as his vice-admiral and rear-admiral. Sir Robert Holmes replaced the captured Ayscue in charge of the remains of the former white squadron, now consisting of between eight and ten of its original twenty ships. Holmes' ships probably formed part of the centre under Albemarle, although its exact position is unclear, and a reduced blue squadron under Thomas Teddiman, its vice-admiral, commanding in the absence of its admiral formed the rear.[102] Like the Dutch, the English fleet spent much of the evening and night repairing damage as far as possible.[103]

Fourth day, first engagements

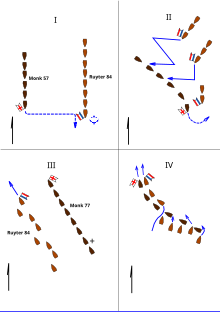

The 4 June was cloudy with a brisk south-westerly wind. Both fleets had moved east of the Galloper Sand on divergent courses and were out of sight of each other at dawn, but English scouting ships soon found the Dutch to the south. When the main English fleet following the scouts was sighted, de Ruyter called his flag officers together to discuss a new arrangement for their nine divisions, with his own squadron in the van, de Vries (as successor to Evertsen) in the centre and Tromp in the rear.[104] His intention was to break the English line in three places simultaneously rather than fight in line ahead.[105] When the English fleet approached, sailing in a south-easterly direction, the Dutch had the weather gauge and sailed in line abreast in a northerly direction before forming line rather obliquely to the English fleet, so that only the Dutch rear and English van were initially within range of each other.[106]

As on previous days, the fleets started by passing each other then reversing course.[107] De Ruyter waited to exploit any gaps that might arise in the English line to carry out his plan of breaking through it, but about 7.30 on the second pass of the fleets, he was forestalled when Rupert's squadron, sailing west, raced for the weather gauge against the leading Dutch ships under Vice Admiral Johan de Liefde with the Ridderschap van Holland as his flagship.[108] De Liefde's immediate opponent was Vice Admiral Myngs on HMS Victory. Myngs' attempt to break the Dutch line was opposed by de Liefde trying to break the English one, but Myngs managed to force his division into the middle of de Liefde's ships[109] In close-quarters fighting, Myngs was shot and fatally wounded and the disabled Victory with three ships protecting it was forced to the north.[110] The Ridderschap van Holland was partly dismasted and unmanageable, but Rupert (who was intent on breaking the Dutch line) ordered his warships to stay in line and sent a fireship to burn it, although it only succeeded in setting fire to a Dutch fireship. The Ridderschap van Holland was then sent to port as being too damaged to continue fighting.[111] Rupert's attempt to break the Dutch line succeeded as HMS Royal James was larger and more strongly armed than any of de Liefde's ships, and many others of Rupert's and Albemarle's ships followed through the gap it had created, or forced their own way through. However, Tromp's rear squadron broke through Teddiman's blue squadron, throwing it into confusion.[112]

Seeing the danger to Teddiman's squadron, both Albemarle and Rupert acted independently to reverse course and attack Tromp with superior numbers. Tromp could not continue on a south-westerly course, as Teddiman's ships were in that direction: he had at most 12 to 14 ships, several of which were small, and could only withdraw to the north. While doing so, two of his ships collided and one the Landman was burned by an English fireship, which also damaged the Gouda severely.[113] De Ruyter had achieved his objective of completely disrupting the English line by late morning, but his own fleet was also in disorder and so unable to take advantage of the confused English fleet.[114]

After Tromp withdrew, gunfire ceased briefly while the disordered fleets tried to rearrange themselves to continue fighting. In the English fleet, Teddiman's rear squadron had first to be brought into line. However, once the English battle line was completed, de Ruyter had at most 35 ships with him, and possibly fewer, to oppose it. Tromp, van Nes (who had decided to chase the four ships from Myngs' former squadron) and de Vries were all some distance away and the English fleet was between them and de Ruyter. The Victory, now commanded by its lieutenant, John Narborough, and its three consorts were attacked by Tromp and van Nes with around 25 ships but managed to manoeuvre to avoid capture and all survived the battle.[115] De Vries ignored this contest, and attempted to rejoin de Ruyter.[116]

Despite having possibly as few as 32 and certainly not more than 35 ships to fight as many as 48 English ones, de Ruyter had regained the weather gauge while Albemarle and Rupert were attacking Tromp. During the late morning and early afternoon, the two fleets passed and repassed each other. Albemarle made no attempt to keep de Vries from joining the main Dutch fleet, which he did around noon. During the successive passes, the English fleet with superior numbers and heavier guns attempted to close with the Dutch, but de Ruyter prudently kept his ships at such a distance that, on some passes, the English ships, some with their magazines depleted by the previous days' fighting, withheld their fire.[117]

De Ruyter's patience was based on the probability that some or all of van Nes and Tromp's 25 ships would return to the main action, which they began to do on the lee side of the English fleet from around 3pm. In response, Albemarle with some 37 ships including Sprague's division from Rupert's white squadron concentrated on van Nes and Tromp while Rupert with around a dozen ships manoeuvred to hold off de Ruyter. Albemarle's intention was to strike a decisive blow before his ammunition and daylight ran out.[118]

Fourth day, de Ruyter's attack

Albemarle and Rupert gambled that de Ruyter would remain to windward and at a distance, so that Rupert's ships could hold them off for long enough for Albemarle to crush Tromp and van Nes. Albemarle attacked at close range and sent in a fireship, both of which caused confusion among the Dutch. Teddiman's Royal Katherine so damaged Tromp's Wapen van Utrecht that Tromp was forced to retire and was unable to return to action; the Dom van Utrecht was forced to surrender to the Royal Charles and several other ships were disabled. Albemarle's policy prohibited his larger ships stopping to take possession of these captured or disabled ships, but he later claimed that his frigates should have set fire to them.[119] Despite this, Albemarle had put a large proportion of the Dutch fleet out of action and his victory seemed certain.[120]

De Ruyter, three miles to windward, looked on anxiously. He had been waiting for several hours for Tromp and van Nes to join him, but they had been routed in a few minutes. He later confirmed that he had thought he had lost the battle, but after consulting Vice Admiral Adriaen Banckert, he waited until Rupert's squadron sailing east had passed his fleet sailing west then crossed Rupert's wake sailing northeast towards Albemarle's rear. At first, Albemarle thought that de Ruyter intended to link up with van Nes and escape with as many Dutch ships as possible, and his exhausted forces with little ammunition left did not move to oppose this manoeuvre.[121]

De Ruyter's unexpected attack, when Albemarle appeared to be on the point of destroying Tromp's squadron, caused some British captains to lose their nerve, and things began to go badly for the English fleet. Rupert in the Royal James and his squadron at first assumed that de Ruyter was withdrawing and had started to make repairs; the masts and rigging of the Royal James in particular had been badly shaken. As soon as he realised that the Dutch were attacking Albemarle, Rupert ordered his ships to attack de Ruyter, who would be trapped between them and the main English fleet.[122] Almost immediately, the Royal James lost its main topmast, its mizzen mast and several major yards: it was now disabled and the rest of the squadron, rather than continuing against the Dutch, withdrew to defend their flagship and tow it westward. Rupert later claimed that there was no other ship he could use as a substitute flagship, but eyewitnesses claimed there were.[123]

Seeing this, de Ruyter realised that he could win the battle and raised the red flag as the signal for an all-out attack, concentrating on the English rear. Albemarle's flagship, the Royal Charles had a damaged foremast and main topmast, and had suffered shot holes to windward, so Albemarle was unable to tack to assist the rear for fear of losing masts or flooding. He also believed that his captains, unnerved by the sudden change of fortune, would not tack at his signal unless the Royal Charles led them.[124] Those English ships of Teddiman's squadron and others in the rear that stayed in line were able to follow Albemarle westwards, as the Dutch were as short of gunpowder as their opponents, and aimed to board and capture them. The Rupert lost a mast, but managed to fight off her pursuers, however the Frisian Rear-Admiral Hendrik Brunsvelt captured the merchant Convertine, which was entangled with HMS Essex and the former Dutch HMS Black Bull which' later sank. Brunsvelt's vice admiral, Rudolf Coenders in Groningen captured HMS Clove Tree (the former VOC-ship Nagelboom).[125]

Fourth day, English retreat

Once the English rear had been subdued, de Ruyter led most of his fleet in pursuit of Albemarle and Rupert, hoping to prevent them joining forces. The English fleet maintained a westward course towards the deep water channel leading to the Thames estuary. Albemarle and Rupert later claimed that their initial aim of their withdrawal was to unite and, if necessary renew the fight the next day, but the poor condition of many ships and their lack of ammunition decided them to continue homeward.[126] However, other English officers said that the Dutch pursued the retreating English fleet for two hours before deciding to retire back to their own harbours.[127]

De Ruyter later claimed that he had called off the pursuit of the English fleet because of a thick fog which made navigation difficult, otherwise he would have followed the ships as far as their home ports. The deeply religious De Ruyter interpreted the sudden unseasonal fog bank as a sign from God, writing in his logbook "that He merely wanted the enemy humbled for his pride but preserved from utter destruction". However, the fog was only temporary and de Ruyter had only around 40 ships under his immediate command, with others disabled and returning to the Netherlands or dealing with prizes, and Albemarle had almost as many, including several large vessels, which posed a significant risk to the exhausted Dutch fleet.[128]

By the end of the third day de Ruyter had already secured strategic victory, as the loss of ships and damage to the remainder would have prevented the English fleet interfering with the Dutch East Indies trade or preventing a French fleet joining the Dutch. Even had he retreated on the fourth afternoon, as Albemarle and Rupert thought, he would only have conceded a limited tactical victory to the English fleet and preserved most of his own fleet. The dismasting of Royal James was an opportunity that de Ruyter seized, but his attack on Albemarle was still a considerable gamble that might not have succeeded if the rest of Rupert's squadron had attacked him rather than withdrawing to the west.[129]

Aftermath

Assessment

The biggest sea battle of the Second Anglo-Dutch War and in the age of sail was undoubtedly a Dutch victory although both sides initially claimed they had won.[b] However, the Dutch fleet had found it difficult to overcome an English fleet that, for the first three days of fighting, was much weaker in numbers than it, and the Dutch had been in danger of defeat on the second and particularly the fourth day.[130] The Dutch had also lost more men killed, mainly on the four ships that had been burned.[131] The absence of the French fleet prevented the possible destruction of the English fleet, so the outcome is sometimes described as inconclusive.[132] Although the Dutch adopted the tactic of fighting in line for the first time, it was not a complete success, as subordinate commanders and individual captains sometimes lacked sufficient discipline to fully exploit this new tactic. The Dutch victory on the fourth day was only won after De Ruyter signalled an "old-fashioned" attack which many of the Dutch were more used to.[133]

Immediately after the battle the English captains of Rupert's squadron, not having seen the outcome, claimed De Ruyter had retreated first, then normally seen as an acknowledgement of the superiority of the enemy fleet. Though the Dutch fleet was eventually forced to end the pursuit, they had managed to cripple the English fleet, at least temporarily, and lost only four smaller ships themselves as the Spieghel refused to sink and was repaired. However, the apparent ascendancy of the Dutch fleet after the Four Days Battle lasted only seven weeks, during which time many damaged English ships were repaired, several others that missed Four Days Battle completed their fitting out and joined the fleet, and a rigorous use of impressment powers ensured the English fleet was adequately manned[134]

Around 1,800 English sailors were taken prisoner and transported to Holland. Many subsequently took service in the Dutch fleet against England. Those that refused to do so remained in Dutch prisons for the following two years.[135]

Later actions

The Dutch leader, Johan de Witt, overestimating the scale of the Dutch victory, ordered de Ruyter to attack and destroy the English fleet while it was anchored in the Thames estuary, while 2,700 Dutch infantry would be transported to the Kent or Essex shores of the Thames to defeat any local militia. This two-pronged attack would, de Witt hoped, end the war in favour of the Dutch Republic. De Ruyter sailed on 25 June and reached the mouth of the Thames on 2 July. Two Dutch squadrons attempted to find a safe passage into the Thames but found the buoys and other navigational aids either removed or placed over sandbanks and a strong English squadron ready to dispute their passage. De Ruyter then decided to blockade the Thames in the hope that what he thought would be the weakened remains of the English fleet would be forced to face him and be destroyed.[136]

Although the restored English fleet had reached numbers equal to de Ruyter's fleet by the first week of July, 1666, Rupert and Albemarle waited until the ships being fitted out and manned joined, and sailed out of the Thames on 22 July.[137] The Dutch fleet moved away from the shallow estuary, and the two fleets met on 25 July at the North Foreland in the St. James's Day Battle. This was an English victory, although not as comprehensive as its commanders wished, because the bulk of the Dutch fleet was not destroyed, although it suffered heavy casualties.[138] The Dutch were, however, demoralised and its commanders indulged in mutual recriminations. After this battle, while the Dutch fleet was being repaired an English squadron, during Holmes' Bonfire entered the Vlie estuary and burned 150 out of a fleet of 160 merchant ships, inflicting severe economic damage on the Netherlands.[139]

The French and the Dutch accused each other of failing to ensure that their respective fleets met as planned. Louis XIV blamed the Dutch for not having its fleet ready in March, which had caused him to delay Beaufort, and the Dutch believed that Louis never intended to risk his fleet in battle.[140] However, on 1 September de Ruyter had anchored his fleet near Boulogne and could have joined Beaufort at Belle-Île, but he withdrew to Dunkirk on 8 September. Meanwhile, Beaufort had left Belle-Île and entered the English Channel reaching Dieppe on 13 September before turning back on finding de Ruyter had withdrawn, losing a new and powerful ship which was captured by four English ones. This ended naval and military cooperation between the two countries.[141]

End of the war

In 1667, the English government was unable to finance a fleet as large and well-manned as that fitted out in July 1666, although such a strong one would have been needed to inflict a serious, and possibly decisive, defeat on the Dutch fleet. This and the Dutch success in the Raid on the Medway made peace inevitable.[142] England had gone to war in the expectation of an early victory that would not overstretch its government's fragile financial position, but both it and the Netherlands had put such unprecedented efforts into providing ships and men that no decisive naval victory was possible, and severe English financial difficulties and the Dutch need to resume unrestricted commercial activity created the conditions for peace without resolving all the underlying causes for the conflict [143]

Popular culture

The Four Days' Battle is dramatized in the Dutch film Michiel de Ruyter (2015), although it is not clear which phase of the battle is shown.[144]

See also

- St. James's Day Battle, the "Two Days' Battle" a few weeks later

- Glossary of nautical terms : (A–L), (M–Z)

Notes

- ^ Dutch: Vierdaagse Zeeslag, also known as the Four Days' Fight

- ^ The contemporaneous Dutch view on this matter was expressed by the poet Constantijn Huygens:

- Two fight — and for their lives

:The one that caused the row

:is beaten — but survives

:And boasts: "I've won it now!

:As master of the field!"

:And did he win? For sure!

:Face-down he couldn't yield:

:His victory was pure

:The other took his hat,

:his rapier and his gold

:And left him lying flat,

:The glorious field to hold

:So master he has been:

:Our Neighbours are the same:

:If thus they like to win,

:we wish them lasting fame

- Two fight — and for their lives

Citations

- ^ Fox, Frank L. (16 July 2009). The Four Days' Battle of 1666: The Greatest Sea Fight of the Age of Sail. Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78346-963-5.

- ^ a b Bodart 1908, p. 793.

- ^ a b Palmer 1997, p. 138.

- ^ a b c Prud'homme van Reine 2009, p. 171.

- ^ Palmer, pp.128-9

- ^ Palmer, pp.131-3

- ^ Palmer, pp.134-5

- ^ Fox, pp. 47-8

- ^ Bruijn, pp.64-6.

- ^ Palmer, pp.138-9

- ^ Bruijn, pp. 64-6

- ^ Palmer, p. 140

- ^ Coggeshall, pp. 13-14

- ^ Rommelse, p.73

- ^ Rommelse, pp.95, 98-9

- ^ Fox, pp.67-8

- ^ Rommelse, pp.100-1

- ^ Rommelse, pp.100, 108-9

- ^ Rommelse, p.109

- ^ Fox, pp.69, 136

- ^ Fox, pp.67-8

- ^ Bruijn, pp. 64-6

- ^ Fox, pp. 126-7

- ^ Jones, pp. 28-9

- ^ Van Foreest and Weber, pp. 1-2, 4

- ^ Fox, pp.99-100

- ^ Fox, pp. 126-7

- ^ Jones, p.19

- ^ Jones, pp. 20-1

- ^ Fox, pp.100-2

- ^ Fox, pp.116-7

- ^ Rommelse, p.110

- ^ Fox, pp.136

- ^ Fox, pp.123-7

- ^ Fox, pp.173-5, 180

- ^ Fox, pp.176-7

- ^ Fox, p. 143

- ^ Fox, pp. 144, 313-5

- ^ Fox, pp. 139, 148, 152

- ^ Allen, pp. 115-16

- ^ Fox, p. 143

- ^ Fox, pp. 155-6

- ^ Fox, p. 157

- ^ Fox, p. 116

- ^ Fox, p. 159

- ^ Fox, pp. 157-8, 160

- ^ Fox, p. 333

- ^ Van Foreest and Weber, pp. 1-2, 4

- ^ Van Foreest and Weber, p. 6

- ^ Fox, p. 182

- ^ Fox, p. 189

- ^ Fox, pp. 190-2

- ^ Fox, pp. 193-4

- ^ Fox, p. 195

- ^ Fox, pp. 195-6

- ^ Van Foreest and Weber, p. 9

- ^ Fox, p. 197

- ^ Fox, pp. 198, 200

- ^ Fox, pp. 201-3

- ^ Fox, pp. 203-4

- ^ Fox, pp. 204-6

- ^ Fox, pp. 207-8

- ^ Fox, pp. 208-9

- ^ Fox, pp. 210-2

- ^ Fox, pp. 213-4

- ^ Fox, pp. 215-8

- ^ Fox, pp. 218-9

- ^ Van Foreest and Weber, p. 11

- ^ Fox, p. 219

- ^ Fox, pp. 219-21

- ^ Fox, p. 222

- ^ Van Foreest and Weber, pp. 13, 15

- ^ Fox, pp. 223-4

- ^ Fox, pp. 223-4

- ^ Van Foreest and Weber, p. 14

- ^ Fox, pp. 224-5

- ^ Fox, pp. 226-8

- ^ Van Foreest and Weber, p. 15

- ^ Fox, pp. 228-9

- ^ Fox, pp. 229-30

- ^ Fox, p. 231

- ^ Fox, pp. 206, 231-2

- ^ Fox, p. 232

- ^ Fox, pp. 232-3

- ^ Fox, pp. 233-4

- ^ Fox, pp. 234-5

- ^ Fox, p. 235

- ^ Van Foreest and Weber, p. 16

- ^ Fox, pp. 235-6

- ^ Van Foreest and Weber, p. 17

- ^ Fox, p. 236

- ^ Fox, pp. 236-8

- ^ Fox, pp. 238-9

- ^ Fox, pp. 239-40

- ^ Fox, pp. 239-40

- ^ Fox, pp. 163-4,-166

- ^ Fox, p. 248

- ^ Van Foreest and Weber, p. 18

- ^ Fox, p. 248

- ^ Fox, p. 248

- ^ Van Foreest and Weber, p. 18

- ^ Fox, pp. 248-9

- ^ Fox, p. 250

- ^ Fox, p. 252

- ^ Van Foreest and Weber, p. 18

- ^ Fox, p. 253

- ^ Fox, p. 254

- ^ Van Foreest and Weber, p. 19

- ^ Van Foreest and Weber, pp. 19-20

- ^ Fox, p. 254

- ^ Fox, pp. 254-5

- ^ Fox, p. 256

- ^ Fox, pp. 256-8

- ^ Van Foreest and Weber, p. 20

- ^ Fox, pp. 258-9

- ^ Fox, p. 259

- ^ Fox, pp. 259-60

- ^ Fox, pp. 260-1

- ^ Fox, pp. 261-2

- ^ Fox, p. 262

- ^ Fox, p. 262

- ^ Fox, pp. 263-4

- ^ Fox, pp. 264-5

- ^ Fox, p. 265

- ^ Fox, pp. 265-7

- ^ Fox, pp. 268-9

- ^ Fox, p. 270

- ^ Fox, p. 270

- ^ Fox, p. 268

- ^ Fox, p. 276

- ^ Fox, p. 275

- ^ Fox, pp. 285-6

- ^ Van Foreest and Weber, p. 23

- ^ Fox, pp. 287-8

- ^ Kemp, pp. 38–9

- ^ Fox, p. 287

- ^ Fox, p. 288

- ^ Fox, pp. 295-6

- ^ Fox, pp. 296-7

- ^ Fox, pp. 173, 176

- ^ Fox, pp. 298-9

- ^ Rommelse, p.175

- ^ Rommelse, pp. 175, 195

- ^ Michiel de Ruyter at IMDb

Bibliography

- Allen, David (1979). From George Monck to the Duke of Albemarle: His Contribution to Charles II's Government, 1660—1670. Biography, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 95–124

- Bruijn, Jaap R. (2011). The Dutch Navy of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-98649-735-3

- Coggeshall, James (1997). The Fireship and its Role in the Royal Navy. Master's Thesis, Texas A&M University

- Fox, Frank L. (2018). The Four Days' Battle of 1666. Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-52673-727-4.

- Jones, J. R. (1988). The Dutch Navy and National Survival in the Seventeenth Century. The International History Review, Vol. 10, No. 1. pp. 18–32

- Kemp, Peter (1970). The British Sailor: A Social History of the Lower Deck. J M Dent & SonsISBN 0-46003-957-1.

- Palmer, M. A.J. (April 1997). "The 'Military Revolution' Afloat: The Era of the Anglo-Dutch Wars and the Transition to Modern Warfare at Sea". War in History. 4 (2): 123–149. doi:10.1177/096834459700400201. JSTOR 26004420. S2CID 159657621.

- Rommelse, G. (2006). The Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665-1667): Raison D'état, Mercantilism and Maritime Strife. Uitgeverij Verloren. ISBN 978-9-06550-9079..

- Van Foreest, HA, Weber, REJ, De Vierdaagse Zeeslag 11–14 June 1666, Amsterdam, 1984.

- Prud'homme van Reine, Ronald (2009). Opkomst en Ondergang van Nederlands Gouden Vloot – Door de ogen van de zeeschilders Willem van de Velde de Oude en de Jonge. Amsterdam: De Arbeiderspers. ISBN 978-90-295-6696-4.

- Bodart, Gaston (1908). Militär-historisches Kriegs-Lexikon (1618–1905). Retrieved 6 June 2023.

10 Annotations

Second Reading

San Diego Sarah • Link

L&M: The Four Days' Battle -- the sharpest engagement of the war fought between the N. Foreland and the Essex coast during 1-4 June, 1666. See https://www.pepysdiary.com/diary/… .

It was a victory for the Dutch, although its effects were to some extent offset by the English victory in the Battle of St. James's Day (25 July, 1666) see https://www.pepysdiary.com/diary/…

San Diego Sarah • Link

This gently-edited excerpt from The Project Gutenberg eBook, “The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783”, by A. T. Mahan and recommended by Ruben in 2008 may be an old book, but it is clear and interesting.

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/13…

Since it’s an eBook I think I’m free to copy and post.

I like it because it is written from the point-of-view of two eye witnesses (one French, one Dutch). They are not as hard on Monck as Pepys and the Diary would lead us to believe.

It’s worth remembering Macaulay's well-known saying: "There were seamen and there were gentlemen in the navy of Charles II; but the seamen were not gentlemen, and the gentlemen were not seamen."

###

We come now to the justly celebrated Four Days' Battle of June 1666, which claims special notice, not only on account of the great number of ships engaged on either side, nor yet only for the extraordinary physical endurance of the men who kept up a hot naval action for so many successive days, but also because the commanders-in-chief on either side, Monck and De Ruyter, were the most distinguished seamen, or rather sea-commanders, brought forth by their respective countries in the 17th century.

Monck was possibly inferior to Blake in the annals of the English navy; but there is a general agreement that De Ruyter is the foremost figure, not only in the Dutch service, but among all the naval officers of that age.

The account about to be given is mainly taken from a recent number of the "Revue Maritime et Coloniale," and is there published as a letter, recently

discovered, from a Dutch gentleman serving as volunteer on board De Ruyter's ship, to a friend in France.

The narrative is delightfully clear and probable --qualities not generally found in the description of those long-ago fights -- and the satisfaction it gave was increased by finding in the Memoirs of the Count de Guiche, who also served as volunteer in the fleet, and was taken to De Ruyter after his own vessel had been destroyed by a fire-ship, an account confirming the former in its principal details.

This additional pleasure was unhappily marred by recognizing certain phrases as common to both stories; and a comparison showed that the two could not be accepted as independent narratives. There are, however, points of internal difference which make it possible that the two accounts are by different eye-witnesses, who compared and corrected their versions before sending them out to their friends or writing them in their journals.

San Diego Sarah • Link

The numbers of the two fleets were: English about 80 ships, the Dutch about 100; but the inequality in numbers was largely compensated by the greater size of many of the English.

A great strategic blunder by the government in London immediately preceded the fight. Charles II was informed that a French squadron was on its way from the Atlantic to join the Dutch. He at once divided his fleet, sending 20 ships under Prince Rupert to the westward to meet the French, while the remainder under Monck were to go east and oppose the Dutch.

A position like that of the English fleet, threatened with an attack from two quarters, presents one of the subtlest temptations to a commander. The impulse is very strong to meet both by dividing his own numbers as Charles did; but unless in possession of overwhelming force it is an error, exposing both divisions to be beaten separately, which, as we are about to see, actually happened in this case. The result of the first two days was disastrous to the larger English division under Monck, which was then obliged to retreat toward Rupert; and probably the opportune return of the latter alone saved the English fleet from a very serious loss, or at the least from being shut up in their own ports.

140 years later, in the exciting game of strategy that was played in the Bay of Biscay before Trafalgar, the English admiral Cornwallis made precisely the same blunder, dividing his fleet into two equal parts out of supporting distance, which Napoleon at the time characterized as a glaring piece of stupidity. The lesson is the same in all ages.

The Dutch had sailed for the English coast with a fair easterly wind, but it changed later to southwest with thick weather, and freshened, so that De Ruyter, to avoid being driven too far, came to anchor between Dunkirk and the Downs.

The fleet then rode with its head to the south-southwest and the van on the right; while Tromp, who commanded the rear division in the natural order, was on the left. For some cause this left was most to windward, the center squadron under De Ruyter being to leeward, and the right, or van, to leeward again of the center.

This was the position of the Dutch fleet at daylight of June 11, 1666; and although not expressly so stated, it is likely, from the whole tenor of the narratives, that it was not in good order.

The same morning Monck, who was also at anchor, made out the Dutch fleet to leeward, and although so inferior in numbers determined to attack at once, hoping that by keeping the advantage of the wind he would be able to commit himself only so far as might seem best.

Monck therefore stood along the Dutch line on the starboard tack, leaving the right and center out of cannon-shot, until he came abreast of the left, Tromp's squadron.

San Diego Sarah • Link

Monck then had 35 ships well in hand; but the rear had opened and was straggling, as is apt to be the case with long columns. With the 35 he then put his helm up and ran down for Tromp, whose squadron cut their cables and made sail on the same tack (V'); the two engaged lines thus standing over toward the French coast, and the breeze heeling the ships so that the English could not use their lower-deck guns.

The Dutch center and rear also cut, and followed the movement, but being so far to leeward, could not for some time come into action.

It was during this time that a large Dutch ship, becoming separated from her own fleet, was set on fire and burned, doubtless the ship in which was Count de Guiche.

As they drew near Dunkirk the English went about, probably all together; for in the return to the northward and westward the proper English van fell in with and was roughly handled by the Dutch center under De Ruyter.

This fate would be more likely to befall the rear, and indicates that a simultaneous movement had reversed the order. The engaged ships had naturally lost to leeward, thus enabling De Ruyter to fetch up with them.

Two English flag-ships were here disabled and cut off; one, the "Swiftsure," hauled down her colors after the admiral, a young man of 27, was killed. "Highly to be admired," says a contemporary writer, "was the resolution of Vice-Admiral Berkeley, who, although cut off from the line, surrounded by enemies, great numbers of his men killed, his ship disabled and boarded on all sides, yet continued fighting almost alone, killed several with his own hand, and would accept no quarter; till at length, being shot in the throat with a musket-ball, he retired into the captain's cabin, where he was found dead, extended at his full length upon a table, and almost covered with his own blood."

San Diego Sarah • Link

Quite as heroic, but more fortunate in its issue, was the conduct of the other English admiral thus cut off; and the incidents of his struggle, although not specially instructive otherwise, are worth quoting, as giving a lively picture of the scenes which passed in the heat of the contests of those days, and afford coloring to otherwise dry details.

"Being in a short time completely disabled, one of the enemy's fire-ships grappled him on the starboard quarter; he was, however, freed by the almost incredible exertions of his lieutenant, who, having in the midst of the flames loosed the grappling-irons, swung back on board his own ship unhurt. The Dutch, bent on the destruction of this unfortunate ship, sent a second which grappled her on the larboard side, and with greater success than the former; for the sails instantly taking fire, the crew were so terrified that nearly 50 of them jumped overboard. The admiral, Sir John Harman, seeing this confusion, ran with his sword drawn among those who remained, and threatened with instant death the first man who should attempt to quit the ship, or should not exert himself to quench the flames. The crew then returned to their duty and got the fire under; but the rigging being a good deal burned, one of the topsail yards fell and broke Sir John's leg. In the midst of this accumulated distress, a third fire-ship prepared to grapple him, but was sunk by the guns before she could effect her purpose. The Dutch vice-admiral, Evertzen, now bore down to him and offered quarter; but Sir John replied, 'No, no, it is not come to that yet,' and giving him a broadside, killed the Dutch commander; after which the other enemies sheered off."

It is therefore not surprising that the account we have been following reported two English flag-ships lost, one by a fire-ship. "The English chief still continued on the port tack, and," says the writer, "as night fell we could see him proudly leading his line past the squadron of North Holland and Zealand [the actual rear, but proper van], which from noon up to that time had not been able to reach the enemy from their leewardly position."

The merit of Monck's attack as a piece of grand tactics is evident, and bears a strong resemblance to that of Nelson at the Nile. Discerning quickly the weakness of the Dutch order, he had attacked a vastly superior force in such a way that only part of it could come into action; and although the English lost more heavily, they carried off a brilliant prestige and must have left considerable depression and heart-burning among the Dutch.

San Diego Sarah • Link

The eye-witness goes on: "The affair continued until ten P.M., friends and foes mixed together and as likely to receive injury from one as from the other. It will be remarked that the success of the day and the misfortunes of the English came from their being too much scattered, too extended in their line; but for which we could never have cut off a corner of them, as we did.

“The mistake of Monck was in not keeping his ships better together;" that is, closed up. The remark is just, the criticism scarcely so; the opening out of the line was almost unavoidable in so long a column of sailing-ships, and was one of the chances taken by Monck when he offered battle.

The English stood off on the port tack to the west or west-northwest, and next day returned to the fight. The Dutch were now on the port tack in natural order, the right leading, and were to windward; but the enemy, being more weatherly and better disciplined, soon gained the advantage of the wind.

The English this day had 44 ships in action, the Dutch about 80; many of the English, as before said, larger. The two fleets passed on opposite tacks, the English to windward; but Tromp, in the rear, seeing that the Dutch order of battle was badly formed, the ships in two or three lines, overlapping and so masking each other's fire, went about and gained to windward of the enemy's van; which he was able to do from the length of the line, and because the English, running parallel to the Dutch order, were off the wind.

"At this moment two flag-officers of the Dutch van kept broad off, presenting their sterns to the English. De Ruyter, greatly astonished, tried to stop them, but in vain, and therefore felt obliged to imitate the maneuver in order to keep his squadron together; but he did so with some order, keeping some ships around him, and was joined by one of the van ships, disgusted with the conduct of his immediate superior.

Tromp was now in great danger, separated [by his own act first and then by the conduct of the van] from his own fleet by the English, and would have been destroyed but for De Ruyter, who, seeing the urgency of the case, hauled up for him," the van and center thus standing back for the rear on the opposite tack to that on which they entered action.

This prevented the English from keeping up the attack on Tromp, lest De Ruyter should gain the wind of them, which they could not afford to yield because of their inferior numbers.

San Diego Sarah • Link

Both the action of Tromp and that of the junior flag-officers in the van, although showing different degrees of warlike ardor, bring out strongly the lack of subordination and of military feeling which has been charged against the Dutch officers as a body; no signs of which appear among the English at this time.

How keenly De Ruyter felt the conduct of his lieutenants was manifested when "Tromp, immediately after this partial action, went on board his flagship. The seamen cheered him; but De Ruyter said, 'This is no time for rejoicing, but rather for tears.'

“Indeed, our position was bad, each squadron acting differently, in no line, and all the ships huddled together like a flock of sheep, so packed that the English might have surrounded all of them with their 40 ships.

“The English were in admirable order, but did not push their advantage as they should, whatever the reason."

The reason no doubt was the same that often prevented sailing-ships from pressing an advantage -- disability from crippled spars and rigging, added to the inexpediency of such inferior numbers risking a decisive action.

De Ruyter was thus able to draw his fleet out into line again, although much maltreated by the English, and the two fleets passed again on opposite tacks, the Dutch to leeward, and De Ruyter's ship the last in his column.

As he passed the English rear, De Ruyter lost his maintopmast and mainyard. After another partial rencounter the English drew away to the northwest toward their own shores, the Dutch following them; the wind being still from southwest, but light.

The English were now fairly in retreat, and the pursuit continued all night, De Ruyter's own ship dropping out of sight in the rear from her crippled state.

San Diego Sarah • Link

The third day Monck continued retreating to the westward. He burned, by the English accounts, three disabled ships, sent ahead those that were most crippled, and brought up the rear himself with those that were in fighting condition, which are variously stated, again by the English, at 28 and 16 in number (June 13).

One of the largest and finest of the English fleet, the "Royal Prince," of 90 guns, ran aground on the Galloper Shoal and was taken by Tromp; but Monck's retreat was so steady and orderly that he was otherwise unmolested. This shows that the Dutch had suffered severely.

Toward evening Rupert's squadron was seen; and all the ships of the English fleet, except those crippled in action, were at last united.

The next day the wind came out again very fresh from the southwest, giving the Dutch the weather-gage. The English, instead of attempting to pass upon opposite tacks, came up from astern relying upon the speed and handiness of their ships.

So doing, the battle engaged all along the line on the port tack, the English to leeward.

The Dutch fire-ships were badly handled and did no harm, whereas the English burned two of their enemies.

The two fleets ran on thus, exchanging broadsides for two hours, at the end of which time the bulk of the English fleet had passed through the Dutch line.

All regularity of order was henceforward lost. "At this moment," says the eye-witness, "the lookout was extraordinary, for all were separated, the English as

well as we. But luck would have it that the largest of our fractions surrounding the admiral remained to windward, and the largest fraction of the English, also with their admiral, remained to leeward. This was the cause of our victory and their ruin.

Our admiral had with him 35 or 40 ships of his own and of other squadrons, for the squadrons were scattered and order much lost.