Wikipedia

This text was copied from Wikipedia on 14 November 2024 at 4:10AM.

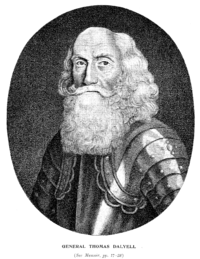

General Thomas Dalyell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1615 |

| Died | 1685 (aged 69–70) |

| Allegiance |  Scotland (1628 to 1654, and 1660 to 1685) Scotland (1628 to 1654, and 1660 to 1685)  Russia (1654 to 1660) Russia (1654 to 1660) |

| Service / branch | Scottish Army |

| Years of service | 1628–1685 |

| Rank | General |

| Battles / wars | Huguenot rebellions |

Sir Thomas Dalyell of The Binns, 1st Baronet (1615 – 1685) was a Scottish Royalist general in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, also known by the soubriquets "Bluidy Tam" and "The Muscovite De'il".

Life

Dalyell was born in Linlithgowshire, the son of Thomas Dalyell of The Binns, head of a cadet branch of the family of the Earls of Carnwath, and of Janet, daughter of the 1st Lord Bruce of Kinloss, Master of the Rolls in England.[2]

He appears to have accompanied Charles I's expedition to La Rochelle in 1628 (to aid the Huguenots during the Siege of La Rochelle) at the age of thirteen. Latterly as a colonel, he served under General Robert Munro and General Alexander Leslie in Ulster.

Hearing of the execution of Charles I on 30 January 1649, it is said that he refused to shave his beard as a penance for the behaviour of his fellow countrymen.[3] He was taken prisoner at the capitulation of Carrickfergus in August 1650, but was given a free pass, and having been banished from Scotland, remained in Ireland.[2]

He was present at the Battle of Worcester (3 September 1651), where his men surrendered, and he himself was captured and imprisoned in the Tower of London. In May he escaped abroad and, in 1654, took part in the Highland rebellion and was exempted from Cromwell's Act of Grace, a reward of 200 guineas being offered for his capture, dead or alive.[4]

Dalyell evaded capture and fled to Russia. There, he entered the service of Tsar Alexis I and distinguished himself as general in the wars against the Turks and Tatars[5] as well as in the Russo-Polish War (1654–1667).

He returned to Britain upon The Restoration of Charles II. By 19 July 1666 he was appointed commander-in-chief in Scotland, with orders to subdue the Covenanters. Dalyell defeated them at the Battle of Rullion Green, in the Pentland Hills, south of Edinburgh. He treated the defeated with great cruelty, earning him the nickname "Bluidy Tam". Legends of his cruelty were probably exaggerated by anti-Royalists. The General obtained several of the forfeited estates of his opponents.[6]

On 3 January 1667 he was made a privy counsellor, and from 1678 till his death he represented Linlithgowshire in the Scottish parliament. He was incensed by the choice of the Duke of Monmouth as commander-in-chief in June 1679, and was confirmed in his original appointment by Charles, but in consequence did not appear at the Battle of Bothwell Brig till after the close of the engagement.[5]

On 25 November 1681, a commission was issued authorizing him to enroll the regiment afterwards known as the Scots Greys. His commission was confirmed by King James VII, but he died soon after the latter's accession in August 1685. He married Agnes, daughter of John Ker of Cavers, by whom he had a son, Thomas, created a baronet in 1685, whose only son and heir, Thomas, died unmarried. The baronetage apparently became extinct, but it was assumed about 1726 by James Menteith.[5] The Dalyell baronetage was later held by politician Tam Dalyell, formally styled Sir Thomas Dalyell of the Binns, 11th Baronet.

Gaming with the devil

Legend has it that "Bluidy Tam" enjoyed on occasion a hand of cards with the devil. During one of these games, the devil, losing, threw the card table at the general. The devil missed and the table flew threw through the window and ended up in a pond on the grounds of the House of the Binns. This tale was passed down through generations of inhabitants of the Binns. In 1870, following a particularly hard drought, a marble topped card table was seen poking through the low waters of the pond. In 1930 the mother of the twentieth century Tam Dalyell asked a local joiner to repair the legs on the table, to find out that the about-to-be-retired tradesman's first job had been to retrieve said table from the pond.[7][8]

Bibliography

- Report on the Muniments of Sir Robert Osborne Dalyell, baronet of Binns, Hist. MSS. Comm. 9th Rep. pt. ii. 230–8

- Captain Creighton's Memoirs in Swift's Works

- Thurloe State Papers, ii.

- State Papers, Dom. Ser., 1654–67

- Wodrow's Sufferings of the Church of Scotland

- Fountainhall's Historical Notices: ib. Observes

- Nicolls's Diary

- Burnet's Own Time

- Balfour's Annals

- Acts of the Parliament of Scotland

- Douglas's Baronage of Scotland

- Grainger's Biog. Hist. of England, 4th ed. iii. 380–1

- Letters to the Duke of Lauderdale, 1666–80

- British Library Add MSS 23125–23126; 23128; 23135; 23246–23247, published in Lauderdale Papers (Camden Society)

- Letters to Charles II, Add MS 28747

- Information from Sir Robert Dalyell, K.C.I.E.

- Foster's Members of Parliament in Scotland, 1882[6]

References

- ^ Paul, James Balfour (1903). An Ordinary of Arms Contained in the Public Register of all Arms and Bearings in Scotland. Edinburgh, W. Green & sons. pp. 291.

- ^ a b Chisholm 1911, p. 779.

- ^ Wood, James, ed. (1907). . The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.

- ^ Chisholm 1911, pp. 779–780.

- ^ a b c Chisholm 1911, p. 780.

- ^ a b Henderson 1888.

- ^ Strange Tales of the Lothians. Lang Syne, Midlothian 1978

- ^ Coventry, Martin. Haunted Castles and Houses of Scotland. 2006. ISBN 9781899874477. Page 136. Retrieved on 20 Mar. 2023. "Sir Tam Dalyell (Bloody Tam) of the Binns was another fellow with a fearsome reputation (musket balls would just bounce off him) and was reputed to have played cards with the Devil."

Sources

- Green, Mary Anne Everett, ed. (1864). Calendar of State Papers Domestic Series of the Reign of Charles 2. Preserved in Her Majestyʼs Public Record Office. London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts and Green. p. 295.

- Henderson, Thomas Finlayson (1888). "Dalyell, Thomas". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 13. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Hewison, James King (1913). "Chapter XXIII – The Ruling of Rothes and the Rising of Rullion Green". The Covenanters. Vol. 2. Glasgow: John Smith and son. pp. 169-220.

- Lamont, John (1830). Kinloch, George Ritchie (ed.). The diary of Mr. John Lamont of Newton. 1649-1671. Edinburgh. p. 196.

- Lee, John (1860). Lectures on the history of the Church of Scotland : from the Reformation to the Revolution Settlement. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: William Blackwood.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Kirkton, James (1817). The secret and true history of the church of Scotland from the Restoration to the year 1678. Edinburgh: J. Ballantyne. p. 249-252,227-228.

- Mackenzie, William, of Galloway; Symson, Andrew (1841). The history of Galloway, from the earliest period to the present time. Vol. 2. Kirkcudbright: J. Nicholson. p. 157-169.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - M'Crie, Thomas (1846). "Chapter III: From 1663 to 1666". Sketches of Scottish church history : embracing the period from the Reformation to the Revolution. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: J. Johnstone. pp. 101-123.

- McIntyre, Neil (2016). Saints and subverters : the later Covenanters in Scotland c.1648-1682 (PhD). University of Strathclyde.

- Sidgwick, Miss M. (1906). "The Pentland Rising and the Battle of Rullion Green". The Scottish Historical Review. 3. Glasgow: James Maclehose & son: 449-452.

- Smellie, Alexander (1903). "How Colonel Wallace fought at Pentland". Men of the Covenant : the story of the Scottish church in the years of the Persecution (2 ed.). New York: Fleming H. Revell Co. pp. 128-139. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- Spalding, John (1828). The history of the troubles and memorable transactions in Scotland and England, from 1624 to 1645. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club. p. 218.

- Spalding, John (1828). The history of the troubles and memorable transactions in Scotland and England, from 1624 to 1645. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club. p. 168.

- Terry, Charles Sanford (1905). The Pentland Rising & Rullion Green. Glasgow: J. MacLehose.

- Turner, James, Sir (1828). Memoirs of his own life and times, 1632–1670. Edinburgh: The Bannatyne Club.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wallace, James (1825). M'Crie, Thomas (ed.). Narrative of the Rising Suppressed at Pentland. Vol. Memoirs of Mr. William Veitch, and George Brysson. Edinburgh; London: W. Blackwood; T. Cadell. pp. 355-432.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Wodrow, Robert (1835a). Burns, Robert (ed.). The history of the sufferings of the church of Scotland from the restoration to the revolution, with an original memoir of the author, extracts from his correspondence, and preliminary dissertation. Vol. 1. Glasgow: Blackie, Fullarton & co., and Edinburgh: A. Fullarton & co. pp. 207-214.

- Wodrow, Robert (1835b). Burns, Robert (ed.). The history of the sufferings of the church of Scotland from the restoration to the revolution, with an original memoir of the author, extracts from his correspondence, and preliminary dissertation. Vol. 2. Glasgow: Blackie, Fullarton & co., and Edinburgh: A. Fullarton & co.

- Wodrow, Robert (1829). Burns, Robert (ed.). The history of the sufferings of the church of Scotland from the restoration to the revolution, with an original memoir of the author, extracts from his correspondence, and preliminary dissertation and notes, in four volumes. Vol. 3. Glasgow: Blackie Fullerton & Co. p. 6.

- Wodrow, Robert (1835d). Burns, Robert (ed.). The history of the sufferings of the church of Scotland from the restoration to the revolution, with an original memoir of the author, extracts from his correspondence, and preliminary dissertation and notes, in four volumes. Vol. 4. Glasgow: Blackie Fullerton & Co. pp. 498-501.

- Wodrow, Robert (1842). Leishman, Matthew (ed.). Analecta: or, Materials for a history of remarkable providences; mostly relating to Scotch ministers and Christians. Vol. 1. Glasgow: Maitland Club. p. 170.

- Wodrow, Robert (1842). Leishman, Matthew (ed.). Analecta: or, Materials for a history of remarkable providences; mostly relating to Scotch ministers and Christians. Vol. 3. Glasgow: Maitland Club. pp. 55-56.

Attribution

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Dalyell, Thomas". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 779–780.

1 Annotation

Second Reading

Bill • Link

General THOMAS DALYELL (DALZIEL) who served Charles the second at the battle or Worcester, and thereafter being taken prisoner by the rebels, after long imprisonment made his escape out of the Tower of London, went to Muscovy, where he served the emperor of Russia as one of the generals of his forces against the Polanders and Tartars, till the year 1665, when he was recalled by king Charles the second; and thereafter did command his majesty's forces at the defeat of the rebels at Pentland-Hills, in Scotland; and continued lieutenant-general in Scotland, when his majesty had any standing forces in that kingdom, till the year of his death, 1685.

Thomas Dalziel, an excellent soldier, but a singular man, was taken prisoner, fighting for Charles II. at the battle of Worcester. After his return from Muscovy, he had the command of the king's forces in Scotland; but refused to serve in that kingdom under the duke of Monmouth, by whom he was superseded only for a fortnight. After the battle of Bothwell-bridge, he, with the frankness which was natural to him, openly reproved the duke for his misconduct upon that occasion. As he never shaved his beard since the murder of Charles I. it grew so long, that it reached almost to his girdle. Though his head was bald, he never wore a peruke; but covered it with a beaver hat, the brim of which was about three inches broad. He never wore boots, nor above one coat, which had straight sleeves, and sat close to his body. He constantly went to London once a year to kiss the king's hand. His grotesque figure attracted the notice of the populace, and he was followed by a rabble with huzzas, wherever he went.

---A Biographical History of England. J. Granger, 1779.