Wikipedia

This text was copied from Wikipedia on 13 January 2025 at 6:10AM.

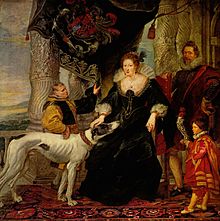

The Earl of Arundel | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Peter Paul Rubens, 1629-1630, National Gallery | |

| Born | 7 July 1585 Finchingfield, Essex |

| Died | 4 October 1646(1646-10-04) (aged 60) Padua, Italy |

| Buried | Fitzalan Chapel, Arundel |

| Noble family | Howard |

| Spouse(s) | Alethea Talbot |

| Issue | Mary Anne Howard, William Howard, 1st Viscount Stafford Henry Howard, 15th Earl of Arundel James Howard, Lord Maltravers |

| Parents | Philip Howard, 13th Earl of Arundel Anne Dacre |

Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel KG, (7 July 1585 – 4 October 1646) was an English peer, diplomat and courtier during the reigns of King James I and King Charles I, but he made his name as a Grand Tourist and art collector rather than as a politician. When he died he possessed 700 paintings, along with large collections of sculptures, books, prints, drawings, and antique jewellery. Most of his collection of marble carvings, known as the Arundel marbles, was eventually left to the University of Oxford.

He is sometimes referred to as the 21st Earl of Arundel, ignoring the supposed second creation of 1289, or the 2nd Earl of Arundel, the latter numbering depending on whether one views the earldom obtained by his father as a new creation or not. He was also 2nd or 4th Earl of Surrey; and was later created 1st Earl of Norfolk (5th creation). He is also known as "the Collector Earl".

Early life and restoration to titles

Arundel was born in relative penury, at Finchingfield in Essex on 7 July 1585.[1] His aristocratic family had fallen into disgrace during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I owing to their Catholic religion and involvement in plots against the Queen. He was the son of Philip Howard, 13th Earl of Arundel, and Anne Dacre, daughter and co-heiress of Thomas Dacre, 4th Baron Dacre of Gilsland. He never knew his father, who was imprisoned before Arundel was born, and owing to his father's attainder he was initially styled Lord Maltravers.[2]

Henry Howard, Earl of Northampton, Arundel's great-uncle helped him regain royal favor upon the accession of James I to the English throne in 1603,[2] and Arundel was restored to his titles and some of his estates in 1604. Other parts of the family lands ended up with his great-uncles. The next year he married Lady Alatheia (or Alethea) Talbot, a daughter of Gilbert Talbot, 7th Earl of Shrewsbury, and a granddaughter of Bess of Hardwick. She would inherit a vast estate in Nottinghamshire, Yorkshire, and Derbyshire, including Sheffield, which has been the principal part of the family fortune ever since. Even with this large income, Arundel's collecting and building activities would lead him heavily into debt.

Diplomatic and political career

In June 1607, Arundel hosted a feast at court and produced a play, The Tragedy of Aeneas and Dido to entertain the Prince de Joinville.[3] Arundel was an effective diplomat during the reign of James I. After coming to court, he travelled abroad, acquiring his taste for art.[2]

He was created Knight of the Garter in 1611. In 1613 he escorted Elizabeth, the electress consort Palatine, to Heidelberg as part of her marriage celebrations, and again visited Italy. On Christmas Day 1616 he took communion in a Church of England service, seen as a true test of his conformity,[4] having been appointed a Privy Councillor in July 1616 [5] He supported Sir Walter Raleigh's expedition to Guiana in 1617, became a member of the New England Plantations Committee in 1620 and planned the colonization of Madagascar.

Arundel presided over the House of Lords Committee in April 1621 for investigating the corruption charges against Francis Bacon, whom he defended from degradation from the peerage, and at whose fall he was appointed a commissioner of the Great Seal. On 16 May 1621, he was briefly sent to the Tower of London by the Lords on account of insulting Baron Spencer by referring to their respective ancestry. He then incurred Prince Charles's and the Duke of Buckingham's anger by his opposition to the (proposed) war with Spain in 1624, and by his share in the duke's impeachment.

On the marriage of his son Henry to Lady Elizabeth Stewart (daughter of Esmé Stewart, 3rd Duke of Lennox) without the king's approval, he was imprisoned in the Tower by Charles I, shortly after his accession, but was released at the instance of the Lords in June 1626, being again confined to his house till March 1628, when he was once more liberated by the Lords. In the debates on the Petition of Right, while approving its essential demands, he supported the retention of some discretionary power by the king in committing to prison. The same year he was reconciled to the king and again made a privy councillor.

On 29 August 1621 Arundel had been appointed Earl Marshal, and in 1623 Constable of England, in 1630 reviving the Earl Marshal's court. He was sent to The Hague in 1632 on a mission of condolence to the king's sister, Elizabeth Stuart, recently Queen of Bohemia, on her husband's death. In 1634 he was made justice in eyre of the forests north of the Trent; he accompanied Charles the same year to Scotland on the occasion of his coronation. In 1635 he was made Lord Lieutenant of Surrey.

In 1636 Arundel undertook an unsuccessful mission to the emperor Ferdinand II to procure the restitution of the Palatinate to Charles I's nephew Charles Louis, whose father had been deposed after claiming and losing the throne of Bohemia.[6] In 1638 he was entrusted with the charge of the forts on the border with Scotland, and, supporting alone amongst the peers the war against the Scots, was made general of the king's forces in the first Bishops' War, though "he had nothing martial about him but his presence and looks."[7] He was not employed in the second Bishops' War, but in August 1640 was nominated captain general south of the Trent.

Arundel was appointed Lord Steward of the royal household in April 1640, and in 1641 as lord high steward presided at the trial of the Earl of Strafford. This closed his public career. He became again estranged from the court, and in 1641 he escorted Marie de' Medici home.[2] In 1642 he accompanied Princess Mary for her marriage to William II of Orange.

Death and succession

With the troubles that would lead to the Civil War brewing, Arundel decided not to return from the Netherlands to England, and instead settled first in Antwerp and then at a villa near Padua, Italy. He contributed a sum of £34,000 to the king's cause, and suffered severe losses in the war.[2]

He died in Padua in 1646, having returned to the Roman Catholicism he nominally abandoned on joining the Privy Council, and was buried in Arundel. He was succeeded as Earl by his eldest son Henry Howard, 15th Earl of Arundel who was the ancestor of the Dukes of Norfolk and Baron Mowbray. His youngest son William Howard, 1st Viscount Stafford was the ancestor of what was first the Earl of Stafford and later Baron Stafford.

Arundel had petitioned the king for restoration of the ancestral Dukedom of Norfolk. While the restoration was not to occur until the time of his grandson, he was created Earl of Norfolk in 1644, which at least ensured the title would stay with his family. Arundel also got Parliament to entail his earldoms to the descendants of his grandfather the 4th Duke of Norfolk.

Collector and patron of the arts

Thomas's trips as special envoy to some of the great courts of Europe further encouraged his interest in art collecting. He became noted as a patron and collector of works of art, described by Walpole as "the father of virtu in England",[8] and was a member of the Whitehall group of connoisseurs associated with Charles I.[9] He commissioned portraits of himself or his family by contemporary masters such as Daniel Mytens, Peter Paul Rubens, Jan Lievens, and Anthony van Dyck. He acquired other paintings by Hans Holbein, Adam Elsheimer, Mytens, Rubens, and Honthorst.

Among Arundel's circle of scholarly and literary friends were James Ussher, William Harvey, John Selden and Francis Bacon. The architect Inigo Jones accompanied Arundel on one of his trips to Italy in 1613 and 1614, a journey which took both men as far as Naples. In the Veneto Arundel saw the work of Palladio which was to become so influential to Jones's later career. Soon after the latter's return to England, he became Surveyor to the King's Works.

Arundel collected drawings by Leonardo da Vinci, the two Holbeins, Raphael, Parmigianino, Wenceslaus Hollar, and Dürer. Many of these are now at the Royal Library at Windsor Castle or at Chatsworth. An inventory of Arundel's paintings was prepared in 1655 following the death of the Countess of Arundel. It was published as part of Mary Hervey's collected edition of his correspondence. The coins and medals were bought by Heneage Finch, Earl of Winchilsea, and dispersed in 1696.

He had a large collection of antique sculptures, the Arundel Marbles mostly Roman, but including some he had excavated in the Greek world, which was then the most important in England. His acquisitions, which also included fragments, pictures, gems, coins, books and manuscripts, were deposited at Arundel House, and suffered considerable damage during the Civil War; due to the war and subsequent neglect nearly half of the marbles were destroyed. After his death, the remaining treasures were dispersed. The marble and statue collection was later bequeathed to Oxford University.[2] It is now in the Ashmolean Museum.

Arundel's important library and its collection of manuscripts was inherited by his son, the 15th Earl, and later by his grandson, Henry Howard (afterwards 6th Duke of Norfolk). In 1666, at the instigation of John Evelyn, who feared its total loss, Henry Howard gave most of it to the Royal Society, and a part, consisting of genealogical and heraldic collections, to the College of Heralds, the manuscript portion of the Royal Society's portion was sold to the British Museum in 1831, and they now form the Arundel manuscripts within the British Library.[10][11]

In 1995, the J.Paul Getty Museum mounted an exhibition of Thomas Howard's and his wife Aletheia's extensive art collection.

Family

With his wife Alethea (married 1606) he had six children,[12]

- James Howard, Lord Maltravers (1607–1624), James VI and I and Anne of Denmark were his godparents.[13]

- Henry Howard, 15th Earl of Arundel (1608–1652)

- William Howard, 1st Viscount Stafford (1614–1680)

- Mary Anne Howard (1614-1658)

References

| This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (December 2018) |

- ^ Hervey 1921, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f Chisholm 1911, p. 708.

- ^ Ambassades de Monsieur de La Boderie, 2 (Paris, 1750), p. 264: Aeneas and Dido: Lost Plays Database

- ^ Chamberlain to Carleton reported this in a letter dated January 4 1616, this is Old Style dating, and so would mean that the letter was written in 1617 by our reckoning. TNA, SP 14/90 f.9.

- ^ TNA, SP 14/88 f.42. See also John Nichols, <it>The progresses, processions, and magnificent festivities, of King James the First</it>, vol. III pp.182, 232.

- ^ Sharpe, Kevin (1992). The Personal Rule of Charles I. p. 519.

- ^ According to Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon; actual source unknown

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ Brown, Jonathan; National Gallery of Art (U.S.) (1995). Kings & Connoisseurs: Collecting Art in Seventeenth-century Europe. A.W. Mellon lectures in the fine arts. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-04497-2. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

- ^ Chisholm 1911, pp. 708–709.

- ^ Nickson, Margaret Annie Eugenie (1998). The British Library : guide to the catalogues and indexes of the Department of Manuscripts. London: British Library. ISBN 0-7123-0660-9. OCLC 40683642.

- ^ Mary F. S. Hervey, The Life, Correspondance and Collection of Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel, Appendix II, p. 459

- ^ Joseph Hunter, Hallamshire (London, 1819), p. 96.

Sources

- Jaffe, David., Allen, Denise., Kolb, Ariane F., Kleeman, Eva, Foister, Susan, et al. The Earl and Countess of Arundel: Renaissance Collectors (Apollo Magazine publication, 1996).

- Chaney, Edward, The Grand Tour and the Great Rebellion (Geneva, 1985).

- Chaney, Edward, The Evolution of the Grand Tour, 2nd ed (London, 2000).

- Chaney, Edward, 'Evelyn, Inigo Jones, and the Collector Earl of Arundel', John Evelyn and his Milieu, eds. F. Harris and M. Hunter (British Library, 2003).

- Chaney, Edward ed., The Evolution of English Collecting (New Haven and London, 2003)

- Chaney, Edward, Inigo Jones's 'Roman Sketchbook', 2 vols (London, 2006).

- Chaney, Edward, "Roma Britannica and the Cultural Memory of Egypt: Lord Arundel and the Obelisk of Domitian", in Roma Britannica: Art Patronage and Cultural Exchange in Eighteenth-Century Rome, eds. D. Marshall, K. Wolfe and S. Russell, British School at Rome, 2011, pp. 147–70.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Arundel, Earls of". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 706–709.

- Hervey, M.F.S. (1921). The Life, Correspondence and Collections of Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel "Father of Vertu in England". Kraus Reprint Company. ISBN 978-0-527-39800-2. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

- Howarth, David, Lord Arundel and his Circle (New Haven and London, 1985).

- Gilman, Ernest B., Recollecting the Arundel Circle (New York, 2002).

- Thomas Howard is portrayed in Le Voleur d'éternité, la vie aventureuse de William Petty, Robert Laffont, 2004, by Alexandra Lapierre, a French novelist.

External links

- Rubens' portrait of the Earl, at the National Gallery

- Van Dyck's portrait at the Getty Museum

- Mytens' portrait at the National Portrait Gallery

- Portrait of Thomas Howard, count of Arundel and his wife Alathea Talbot Sir Anthony Van Dyck

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1891). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 28. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

0 Annotations