Wikipedia

This text was copied from Wikipedia on 14 December 2024 at 5:10AM.

Nicolas Fouquet | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Charles Le Brun | |

| Born | (1615-01-27)27 January 1615 |

| Died | 23 March 1680(1680-03-23) (aged 65) |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Superintendent of Finances in France |

| Signature | |

| |

Nicolas Fouquet, marquis de Belle-Île, vicomte de Melun et Vaux (French pronunciation: [nikɔla fukɛ]; 27 January 1615 – 23 March 1680) was the Superintendent of Finances in France from 1653 until 1661 under King Louis XIV. He had a glittering career, and acquired enormous wealth. He fell out of favor, accused of peculation (maladministration of the state's funds) and lèse-majesté (disrespect to the monarch). The king had him imprisoned from 1661 until his death in 1680.

Early life

Nicolas Fouquet was born in Paris to an influential family of the noblesse de robe (members of the nobility under the Ancien Régime who had high positions in government, especially in law and finance). He was the second child of François IV Fouquet (who held numerous high positions in government) and of Marie de Maupeou (who came from a family of the noblesse de robe and who was famous for her piety and charitable works).[1]:18–23,[2]

Contrary to the pretensions of the family, the Fouquets did not come from a lineage of noble blood. They were originally, in fact, merchants in the cloth trade, based in Angers. Fouquet's father later amassed great wealth as a shipowner in Brittany. He was noticed by Cardinal Richelieu, who gave him important positions in government. In 1628, he became an executive associate in the Company of the American Islands,[2] a chartered company for the colonization of French Islands, including missionary work and trade and investment.[1]:18–23

Fouquet's family was extremely devout. They had planned that Nicolas would join the clergy. Out of the family’s 11 children[4] who survived into adulthood, all 5 girls took vows. Among the male children, 4 took the cloth and 2 became bishops.[2] Only Nicolas and his brother Gilles were laymen.[5]:51

After some preliminary schooling with the Jesuits at the age of 13, Fouquet received his law degree from the University of Paris. Richelieu advised Fouquet on this career choice.[3]:40

Political career

In 1634, Fouquet was appointed councilor of the Parliament of Metz. Richelieu charged him with the sensitive task of verifying the accounts to determine whether or not Charles IV of Lorraine was skimming money that rightfully was due to the King of France. Fouquet, still a teenager, accomplished this task with brio.[3]:40–41 In 1636, at just 20, his father bought him the post of maître des requêtes for 150,000 livres (under the Ancien Régime, many government posts were purchased by the people holding them).[1],[6] In 1640, he married the rich and well-connected Louise Fourché and received around 160,000 livres from the dowry, plus other rents and land. Louise died in 1641 at the age of 21, six months after giving birth to a daughter. Fouquet was 26 years old.[7]

Cardinal Richelieu died in 1642, but Fouquet was successful in impressing his successor as chief minister, Cardinal Mazarin, who became his protector (over the long term, the relationship was tense[8]:59–60). From 1642 to 1650, Fouquet held various intendancies, at first in the provinces and then with the army of Mazarin.[3] In 1648, Fouquet was named general intendant of Paris, right as the second Fronde broke out. He ably came to the aid of Mazarin and the Queen Mother, Anne of Austria (who was regent for the young Louis XIV) in defense of the monarchy. As a result, Fouquet earned the lasting loyalty and support of both Mazarin[8]:30 and Anne.

These high-level positions raised his profile with the court. He was permitted in 1650 to buy, for 450,000 livres, the important position of procureur général to the parlement of Paris, thereby raising him to the most elite ranks of the noblesse de robe.

Fouquet's already great wealth was augmented by his marriage in 1651 to 15-year old Marie-Madeleine de Castille. She belonged to a wealthy, well-connected family of the noblesse de robe.[3]:77 Fouquet had five children with her.[4]

During Mazarin's exile during the second Fronde, Fouquet remained loyal to him, protecting his possessions and informing him of what was happening in the court.[8]:59–60 Upon Mazarin's return, Fouquet demanded and received as a reward the office of superintendent of finance (on 7 February 1653),[9] making him the youngest person to hold this position in the Ancien Regime.

The royal finances were in a disastrous state at this time, due to many years of war under Cardinals Richelieu and Mazarin and antiquated revenue practices. Only about half of total tax revenues collected actually ended up in the royal treasury, the rest being skimmed off by various parties along the way. In this unsettled situation, Fouquet was responsible for decisions as to which funds should be used to meet the demands of the state's creditors, but also for the negotiations with the great financiers who lent money to the king.[10] Fouquet's willingness to honor some of the royal promises enhanced the credibility of the crown as a borrower and strengthened the credit of the government, though the controls on this process were either ineffective or non-existent. The long wars, and the greed of the courtiers, made it necessary at times for Fouquet to meet the demand for funds by borrowing upon his own good credit.[8]:33–42 Fouquet was aware of the risks he was running – he feared ruining his family and his friends who had helped him lend money to the crown. In December 1658, he presented his resignation to Mazarin, but, unfortunately for him, it was not accepted.[11]

The disorder in the accounts became hopeless, but was also normal – the kingdom had a long history of poorly controlled royal finances. In any case, debt issuance could not resolve the deplorable economic situation of the realm without an underlying ability and willingness to rein in expenditures and to bring in tax revenues. Fouquet became the central actor in a debt situation that was fundamentally untenable. Fouquet had drawn up a plan to bring some order to public finances, but he never made progress in implementing it, though it was taken up later by Colbert.[8]:63 Instead, it was business as usual: fraudulent operations were entered into with impunity, and the financiers were maintained in the position of clients via official favours and generous aid whenever they needed it. In the meantime, the peasants and commoners in the cities paid the price for this disorder.[8]:33–42

With Mazarin's death on 9 March 1661, Fouquet expected to be made chief minister, but Louis XIV was suspicious of his loyalty to the crown and his poorly disguised ambition. Upon assuming his kingly duties, it was with Fouquet in mind that Louis XIV made the well known statement that he would be his own chief minister. Colbert, perhaps seeking to succeed Fouquet,[12] fed the king's displeasure with adverse reports about the deficit and unflattering reports about Fouquet. However, Fouquet had some protections – his high position at the parlement (he remained procureur général) gave him immunity from prosecution by any authority except the Parlement, which he largely controlled.[13] Another reason Fouquet may have felt secure is that what he was doing was not necessarily illegal – even Colbert later admitted that "Fouquet managed to conduct his robbery while keeping his hands clean."[8]:40

Vaux-le-Vicomte

In 1641, the 26-year old Fouquet purchased the manor of Vaux-le-Vicomte and its small castle located 50 km south east of Paris. He spent enormous sums over a period of 20 years building a château on his estate. In terms of its size, magnificence and interior decor, the chateau was the forerunner of the Palace of Versailles. To design it, he brought together a team that the king later used for Versailles: the architect Louis Le Vau, the painter Charles Le Brun, and the garden designer André le Nôtre.[14]

At Vaux and other major properties he owned (notably, his estate in Saint-Mandé, which bordered on the Château de Vincennes), Fouquet gathered rare manuscripts, paintings, jewels and antiques in profusion, and above all surrounded himself with artists and authors. Jean de La Fontaine, Pierre Corneille, Molière, Madame de Sevigné and Paul Scarron were a few of the many artists and authors who received his invitations, and for some, his patronage.[8]:89–90

These extravagant expenditures and displays of the superintendent's wealth ultimately intensified the ill-will of the king.

Colonial and maritime activities

In 1638, Fouquet received as a gift some of his father's shares in the Company of the American Islands. In 1640, he became one of the first shareholders in the Société du Cap Nord and, in 1642, of the East India Company (Société des Indes Orientales). After his father’s death in 1641, he inherited and managed the family's interests in several other chartered companies for French colonization (Sénégal, New France). Moreover, the family, through Fouquet's father and other family ties, was already active in maritime transport and had a network of influential contacts in Brittany.1:131

Over a period of many years, Fouquet undertook to develop these existing strengths. Specifically, Fouquet was active in attempting to forward the French colonial effort and in developing the coast of Brittany as a major location for hosting maritime trade. He cultivated high ranking friends in Brittany. He bought numerous armed ships and proceeded with a quasi-military development,[3]:315 apparently without informing the king.

As part of this undertaking, Fouquet had bought Belle-Île-en-Mer in 1658, an island off the coast of Brittany. He strengthened the island’s existing fortifications and built a port and warehouses (he also fortified the île d'Yeu). These were major construction projects which caused the king enough concern that he had a spy sent to Belle-Île-en-Mer. The spy reported that there was a garrison of 200 soldiers, 400 cannon and a stockpile of ammunition sufficient for a force of 6000 soldiers. Fouquet planned to use Belle-Île as a refuge in case of disgrace.[3]:315,[13]

Heightening the concerns of the king, Fouquet was found to have ordered several warships in the Netherlands, which could have served both his colonial ambitions and as an implicit threat to the king.[9] In addition, Fouquet used a straw man to assume the position of Viceroy (vice-roi) of the Americas without the king’s knowledge.[13]

Arrest

On 17 August 1661, Louis was entertained at Vaux-le-Vicomte with a sumptuous fête, at which Molière's Les Fâcheux was produced for the first time. The fête also included a lavish meal served on gold and silver plates for hundreds of members of the court; there were also fireworks, a ballet and light shows. The king was astounded by this display of luxury.[9][13]

Although this fête is sometimes cited as the reason for Fouquet's downfall,[9] Louis XIV secretly was plotting with Colbert to get rid of him in May and June 1661. The splendour of the entertainment only aggravated Fouquet's precarious position by calling attention to the immense gap between his ostentatious wealth and the visible poverty of the crown.[3]334,[15]

The king was also concerned about Fouquet's carefully cultivated network of friends and clients, which made him one of the most influential individuals in the realm.[9] Then only 22 years old, the king was afraid to act openly against so powerful a minister.[16] As a child, Louis had observed the armed conflict that threatened his monarchy during the Fronde and had solid reasons to be concerned about rebellion. As superintendent, Fouquet headed the enormously wealthy and influential corps of partisans (tax farmers), which, if challenged as a group, could have caused the king serious trouble.[17]

By crafty devices, Fouquet was induced to sell his office of procureur général, causing him to lose his immunity from royal prosecution; he paid the money received from the sale (about 1 million livres) into the royal treasury as a gesture to earn the favor of the king.[18]:140,[13] At the same time, he was weighed down by his own recent faux pas – notably, when he tried unsuccessfully to recruit a mistress of the king as a spy (the mistress refused Fouquet's offer of money and duly reported it to the king).[9]

After his visit to Vaux, the king announced that he was going to Nantes for the opening of the meeting of the provincial estates of Brittany. He required his ministers, including Fouquet, to go with him. On 5 September 1661, Fouquet was leaving the council chamber, flattered with the assurance of the king's esteem, when he was arrested by d’Artagnan, lieutenant of the king's musketeers. It is reported that the arrest took Fouquet completely by surprise because he apparently thought that he was very much in the king's good graces.[13] He initially was imprisoned at the Chateau d’Angers.[9]

Trial and life imprisonment

The trial lasted almost three years. Many procedural aspects of the investigation and trial were highly questionable, even by the standards of the 17th century. For example, the officials charged with the investigation answered directly to Fouquet's arch-enemy, Jean-Baptiste Colbert; the trial was held before a special court where judges and prosecutors were handpicked by Colbert for being hostile to Fouquet and sympathetic to the king;[19]:156 and the trial was held in written form – Fouquet, a convincing orator, was not allowed to speak in his own defense.[9]

Nevertheless, some of the charges against Fouquet were supported by evidence that Fouquet found difficult to refute, notably the ‘cassette of Saint Mandé’. The cassette contained incriminating documents that had been found after his arrest; they were hidden behind a mirror in Fouquet's estate near Paris. The cassette contained a plan of defence written in 1657 at a time when Fouquet was on bad terms with Mazarin, that was modified in 1659. The plan instructed his supporters on what they should do if he were ever to be arrested, including taking up arms. It also envisaged a naval operation in the Bay of the Seine.[20]

The accusations that were the subject of the trial could be punishable by death.[9] They were:

- Misdeeds in the administration of royal finances and misuse of public funds (peculat, a capital crime). This accusation included: appropriation of large sums of the Crown’s money; receiving payments from illegally acquired rents; lending money to the king while serving as ordonnateur (a public function for regulating public expenditures and receipts); and the private use of funds from the royal treasury.

- The crime of lèse-majesté, including the purchase of Belle-Île without the king’s authorization; corruption of royal officers and governors in a fortified place; and conflict of interest, notably with high-ranking members of the king’s court.[9]

During the trial, French public sympathy tended to support Fouquet. La Fontaine, Madame de Sévigné, Jean Loret, and many others wrote on his behalf.

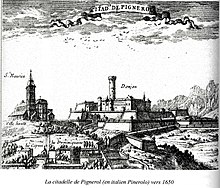

The guilty verdict and the sentence of banishment were handed down on 20 December 1664 – out of 22 judges, 13 were for banishment and 9 were for the death penalty.[19] The king, disappointed with what he regarded as a lenient decision, "commuted" the sentence to life imprisonment at the fort of Pignerol and confiscation of Fouquet's property.[8]:167 He also launched a vendetta against Fouquet's friends, supporters and family.[21],[8]:150–152

In December 1664, Fouquet was taken to the prison fortress of Pignerol in the Alps (in what is now Italy). He remained there, incarcerated in harsh conditions, until his death in 1680.

There, Eustache Dauger, the man identified by historical research as the Man in the Iron Mask but whose real name never was spoken or written, is said to have served as one of Fouquet's valets (but the link between Fouquet's imprisonment and the Man in the Iron Mask is controversial[9]). Fouquet's wife was not allowed to write to him until 1672 and she was allowed to visit him only once, in 1679.[6] The former minister bore his imprisonment with fortitude; he composed several translations and devotionals there.[8]:156, 167

Death

According to official records, Fouquet died in Pignerol on 23 March 1680. His son, the Count of Vaux, was with him when he died. Although no death certificate was established, he is said to have died of apoplexy following a long illness. He was initially buried in the local church, Saint Claire de Pignerol. However, a year after his death, his remains were moved from there to the unmarked family crypt in the Église Sainte-Marie-des-Anges in Paris.[22]

In fiction

Fouquet's story is often entwined with that of the Man in the Iron Mask, who is often identified as the true king or even as an identical twin brother of Louis XIV. As such, he is a pivotal character in Alexandre Dumas' novel The Vicomte de Bragelonne, where he is depicted heroically. Aramis, an ally of Fouquet, tries to seize power by replacing Louis XIV with his identical twin brother. It is Fouquet who, out of sheer loyalty to the crown, foils Aramis's plot and saves Louis. This does not, however, prevent his downfall.

James Whale's film The Man in the Iron Mask (1939) is very loosely adapted from Dumas' novel, and by contrast, depicts Fouquet as the story's main villain, who tries to keep the existence of the king's twin brother a secret. Fouquet is portrayed by Joseph Schildkraut. In the 1977 version, Fouquet is portrayed by Patrick McGoohan. In The Fifth Musketeer (1979), based on the same novel, he is portrayed by Ian McShane. In a departure from history, most of these films show him dying in the 1660s.

Fouquet was portrayed by Robert Lindsay in Nick Dear's play Power.

Fouquet's life (and his rivalry with Colbert) is one of the background plots/stories in the historical novel Imprimatur by Rita Monaldi and Francesco Sorti.

Fouquet and his arrest also figure prominently in Roberto Rossellini's 1966 film The Taking of Power by Louis XIV, where Fouquet is played by Pierre Barrat.

In the second of Peter Greenaway's Tulse Luper films, a Nazi general by the name of Foestling, played by Marcel Iureș, becomes obsessed with Fouquet and attempts to recreate his life and death.

Fouquet is described but not mentioned by name in an episode of HBO's The Sopranos. Carmine Lupertazzi Jr. makes a comparison of John Sacrimoni to King Louis' finance minister who tried to outshine him and his estate: "In the end, Louis clapped him in irons".

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Fouquet, Nicolas". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 750–751.

- The page numbers the biographies of Fouquet written by Dessert and Petitfils are taken from the French Wikipedia article about Fouquet.

References

- ^ a b Dessert, Daniel (1984). Argent, pouvoir et société au grand siècle (in French). Paris: Fayard. ISBN 2-213-01485-X.

- ^ a b c de Maupeou, Jacques (1949). "La Mère de Fouquet". Hommes et Mondes. 9 (34): 73–90. ISSN 0994-5873. JSTOR 44206996.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Petitfils, Jean-Christian (1998). Fouquet (in French). Paris: Perrin. ISBN 2262023328.

- ^ a b "Généalogie de François Fouquet". Geneanet (in French). Retrieved 2022-01-30.

- ^ Dessert, Daniel (1984). Argent, pouvoir et société au grand siècle (in French). Paris: Fayard. ISBN 2-213-01485-X.

- ^ a b Volker Steinkamp (14 August 2011). "Das letzte Fest des Nicolas Foucquet". Die Zeit (in German).

- ^ "Généalogie de Nicolas Fouquet le Surintendant des finances". Geneanet (in French). Retrieved 2022-01-31.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Morand, Paul (1985). Fouquet, ou Le Soleil offusqué (in French). Paris: Gallimard, collection Folio Histoire. ISBN 2-07-032314-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Le procès de Nicolas Fouquet". justice.gouv.fr (in French). Retrieved 2022-01-29.

- ^ Bluche, François (1986). Louis XIV (in French). Paris. ISBN 2213015686.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Murat, Inès (1980). Colbert (in French). Paris: Fayard. p. 79. ISBN 2213006911.

- ^ Lossky, Andrew (1967), The Seventeenth Century: 1600–1715. Free Press. p. 280.

- ^ a b c d e f "[CEH] L'arrestation de Nicolas Fouquet (1/2)". Vexilla Galliae (in French). 2020-07-25. Retrieved 2022-01-30.

- ^ "Three centuries of history". Vaux le Vicomte. Retrieved 2022-02-01.

- ^ Louis XIV so states in a letter to his mother, dated 5 September 1661, reproduced in English translation in Lossky (1967: 340–342).

- ^ For the king's caution, see, for example, letter of Louis XIV to the Comte d'Estrades, dated 16 September 1661, reproduced in English translation in Lossky (1967: 342–345).

- ^ Braudel, Fernand (1979), The Wheels of Commerce [Les Jeux de l'Echange]: Civilization and Capitalism 15th–18th Century, v. 2. English ed., Sîan Rynolds (transl.), Harper & Row (1982) pp. 538–539.

- ^ Dessert, Daniel (1984). Argent, pouvoir et société au grand siècle (in French). Paris: Fayard. ISBN 2-213-01485-X.

- ^ a b Inés Murat (1980). Colbert. Fayard. Paris. pp. 420–421. ISBN 2-213-00691-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Galliae, Vexilla (2020-07-31). "[CEH] L'arrestation de Nicolas Fouquet (2/2)". Vexilla Galliae (in French). Retrieved 2022-02-02.

- ^ A report of Fouquet's trial was published in the Netherlands, in 15 volumes, in 1665–67, in spite of the remonstrances which Colbert addressed to the Estates-General. A second edition under the title of Oeuvres de M. Fouquet appeared in 1696.

- ^ Pénin, Marie-Christine. "Couvent des Filles de la Visitation Sainte-Marie de la rue Saint-Antoine". Tombes Sépultures dans les cimetières et autres lieux.

0 Annotations