Wikipedia

This text was copied from Wikipedia on 18 December 2024 at 4:11AM.

Earl of Warwick | |

|---|---|

| |

| Lord Lieutenant of Essex | |

| In office 1625–1642 | |

| Governor of Guernsey | |

| In office 1643–1645 | |

| Member of Parliament for Essex | |

| In office April 1614 – June 1614 | |

| Member of Parliament for Maldon | |

| In office February 1610 – February 1611 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | May/June 1587 Leez Priory, Essex |

| Died | 18 April 1658(1658-04-18) (aged 70) Holborn, London |

| Resting place | Holy Cross Church, Felsted |

| Spouse(s) | Frances Hatton (m. 1605) Susan Rowe (m. c. 1625) Eleanor Wortley (m. 1646) |

| Children | 5, including Anne, Robert and Charles |

| Parent(s) | Robert Rich, 1st Earl of Warwick Penelope Devereux |

| Alma mater | Emmanuel College, Cambridge |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | Royal Navy |

| Rank | Admiral |

| Battles/wars | Wars of the Three Kingdoms |

Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of Warwick KB, PC (May/June 1587 – 19 April 1658) was an English naval officer, politician and peer who commanded the Parliamentarian navy during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A Puritan, he was also lord of the Manor of Hunningham.[1]

Personal details

Robert Rich was the eldest son and third of seven children born to Robert Rich, 1st Earl of Warwick (1559–1619) and his first wife Penelope (1563–1607). His parents separated soon after his brother Henry's birth, although they did not formally divorce until 1605, when Penelope married her long-time partner, Charles Blount, 8th Baron Mountjoy (1563-1606). Penelope was a sister of the Earl of Essex, executed for treason in 1601, making Rich a cousin to future Parliamentarian general Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex.[2]

He had two sisters, Essex (1585-1658) and Lettice (1587-1619) and a younger brother Henry Rich, 1st Earl of Holland (1590–1649). He also had a number of half brothers and sisters, including Penelope (1592-?), Isabella, Mountjoy Blount, 1st Earl of Newport (1597-1666), and Charles (1605-1627). Almost certainly fathered by Charles Mountjoy, these children were brought up within the Rich family and appear in its pedigree, with the exception of Mountjoy, who was legitimised after his father's death.[3]

Robert Rich married three times, first in February 1605 to Frances Hatton (1590–1623) Lady of the Manor of Hunningham,[1] daughter and heiress of Sir William Hatton (1560–1597)[4] Lord of the Manor of Hunningham,[1] formerly "Newport",[5] the granddaughter of Francis Gawdy. Their children included Anne (1604–1642), Robert (1611–1659), Lucy (1615–after 1635), Frances (1621–1692) and Charles (1623?–1673). Sometime before January 1626, he married Susan Rowe (1582–1646), a daughter of Sir Henry Rowe, Lord Mayor of London, and widow of William Holliday (c.1565–1624), Alderman of London, a wealthy London merchant and chairman of the East India Company. In March 1646, he made his third and last marriage to Eleanor Wortley (died 1667); neither of these produced children.[6]

Career

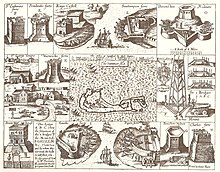

He succeeded to his father's title as Earl of Warwick in 1619. Early developing interest in colonial ventures, he joined the Guinea, New England, and Virginia companies, as well as the Virginia Company's offspring, the Somers Isles Company (the Somers Isles, or Bermuda, was at first the more secure of the Virginia Company's two settlements, being impossible to attack overland and almost impregnable against attack from the ocean due to its encircling reef, and was attractive as a base of operations for Warwick's privateers, though his ship the Warwick was lost at Castle Harbour in November 1619).[7][8]

He was also instrumental in the establishment of the ill-fated Providence Island colony in the West Indies (which was also linked with his privateering activities). Warwick's enterprises involved him in disputes with the East India Company (1617) and with the Virginia Company, which in 1624 was suppressed as a result of his action. In August 1619, the White Lion, a privateer ship sponsored by him and operating under a Dutch letter of marque, attacked the Portuguese slave ship São João Bautista and captured approximately 20 African slaves. The White Lion proceeded to sail to Old Point Comfort in the English colony of Virginia, where its crew sold the Africans to the colony's settlers, including Governor George Yeardley. This event is considered by historians to be a major event in slavery in the colonial history of the United States.[9][10] In 1627, he commanded an unsuccessful privateering expedition against the Spanish.[11] He sat as a Member of Parliament for Maldon for 1604 to 1611 and for Essex in the short-lived Addled Parliament of 1614.[12]

Colonial ventures

Warwick's Puritan connections and sympathies gradually estranged him from the court but promoted his association with the New England colonies. In 1628 he indirectly procured the patent for the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and in 1631 he was granted the "Saybrook" patent in Connecticut. Forced to resign the presidency of the Council for New England in the same year, he continued to manage the Somers Isles Company (the Somers Isles being one of the colonies that sided with the Crown) and Providence Island Company, the latter of which, founded in 1630, administered Old Providence on the Mosquito Coast. Meanwhile, in England, Warwick opposed the forced loan of 1626, the payment of ship money, and Laud's church policy.[11]

His Richneck Plantation was located in what is now the independent city of Newport News, Virginia. The Warwick River, Warwick Towne, Warwick River Shire, and Warwick County, Virginia are all believed named for him, as are Warwick, Rhode Island and Warwick Parish in Bermuda (alias The Somers Isles). The oldest school in Bermuda, Warwick Academy, was built on land in Warwick Parish given by the Earl of Warwick; the school was begun in the 1650s (its early records were lost with those of the Warwick Vestry in a twentieth-century shipwreck), though the school places its founding officially in 1662.[13]

The Long Parliament

By the summer of 1640 Warwick had emerged as the centre of the resistance to Charles I. [14] This was the result of decades of resisting actions including opposing Charles I's compulsory loans during the 1620s and in January 1637 – 12 years into Charles I’s personal rule – personally presenting the case for a new parliament to the king. [15]

In September 1640, Warwick signed the Petition of Twelve to Charles I, asking the king to summon another parliament.[16]

Over the early part of the new parliament, Warwick led one wing of the opposition to Charles I. The Warwick House group pushed for further reform than the more conciliatory Bedford House group, and in particular urged the need for the execution of the Earl of Stratford. [15]

Civil War period

In 1642, following the dismissal of the Earl of Northumberland as Lord High Admiral, Warwick was appointed commander of the fleet by Parliament.[17] In 1643, he was appointed head of a commission for the government of the colonies, which the next year incorporated Providence Plantations, afterwards Rhode Island, and in this capacity, he exerted himself to secure religious liberty.[11]

As commander of the fleet, in 1648, Warwick retook the 'Castles of the Downs' (at Walmer, Deal, and Sandown) for Parliament, and became Deal Castle's captain 1648–53.[18] The subject was criticized for not recapturing the royalist fleet in 1648 when Prince Rupert suffered mutiny and disarray in Hellevoetsluis.[19] However, he was dismissed from office on the abolition of the House of Lords in 1649. He retired from national public life, but was intimately associated with the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell, whose daughter Francis married his grandson and heir, also Robert Rich, in 1657 (the marriage was a short one as the grandson died the following year).[11]

References

- ^ a b c Hunningham, in A History of the County of Warwick: Vol. 6, Knightlow Hundred, ed. L F Salzman (London, 1951), pp. 117–120.

- ^ Smut 2004.

- ^ Usher 2004.

- ^ Salzman, L F. "Parishes: Wellingborough Pages 135-146 A History of the County of Northampton: Volume 4". www.british-history.ac.uk. Victoria County History, 1937. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ Aughterson 2004.

- ^ Kelsey 2004.

- ^ Bojakowski, Katie (2014). "The Wreck of the Warwick, Bermuda 1619". tDAR (the Digital Archaeological Record). Center for Digital Antiquity, a collaborative organization and university Center at Arizona State University. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ Inglis, Doug (5 June 2012). "1619: Unrecoverably lost in Castle Harbour". Warwick, 1619: Shipwreck Excavation. The Warwick Excavation is a National Museum of Bermuda (NMB) project in partnership with Texas A&M and the Institute of Nautical Archaeology (INA), in association with The Global Exploration and Oceanographic Society (G-EOS) and Department of Archaeology at the University of Southampton. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ 400 years ago, enslaved Africans first arrived in Virginia, https://www.nationalgeographic.com. Accessed 9 January 2023.

- ^ The First Africans in Virginia Landed in 1619. It Was a Turning Point for Slavery in American History — But Not the Beginning, time.com. Accessed 9 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Warwick, Sir Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 349.

- ^ "RICH, Sir Robert (c.1588–1658), of Wallington, Norf., Hackney, Mdx. and Allington House, Holborn, Mdx.; later of Leez Priory, Essex". History of Parliament Trust. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ Warwick Academy, warwickacad.bm. Accessed 9 January 2023.

- ^ John Adamson. (2007). The Noble Revolt. Phoenix, London, UK. ISBN 9780753818787.

- ^ a b Adamson, John; The Noble Revolt; 2009

- ^ Kelsey 2004

- ^ "July 1642: Ordinance for the Earl of Warwick to remain in his Command of the Fleet", Acts and Ordinances of the Interregnum, 1642–1660 (1911), p. 12. Accessed 13 April 2007.

- ^ 13 July 1648: "Taking of Walmer Castle", British-history.ac.uk. Accessed 6 August 2007.

- ^ Richard J Blakemore and Elaine Murphy. (2018). The British Civil Wars at Sea, 1638-1653. Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: The Boydell Press. pp. 149–152; ISBN 9781783272297.

Sources

- Aughterson, Kate (2004). "Hatton, Elizabeth, Lady Hatton [née Lady Elizabeth Cecil] (1578–1646)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/68059. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Gowdy, Mahlon M (1919). A Family History Comprising the Surnames of . . . Gawdy. Journal Press.

- Kelsey, Sean (2004). "Rich, Robert, second earl of Warwick (1587–1658)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23494. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Harris, Nicolas (1847). Memoirs of the Life and Times of Sir Christopher Hatton. Richard Bentley.

- Smut, R Malcolm (2004). "Rich, Henry, first earl of Holland (1598-1649)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23484. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Usher, Brett (2004). "Rich, Robert, first earl of Warwick". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/61021. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

External links

Media related to Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of Warwick at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of Warwick at Wikimedia Commons

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notes: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

3 Annotations

First Reading

JWB • Link

"Earl of Warwick, Robert Rich, 1587-1658

The eldest son of Robert Rich, 1st Earl of Warwick and of his wife Penelope Rich. He succeeded to the earldom of Warwick in 1619 and was active in colonial ventures in New England and the West Indies during the 1620s and '30s. Warwick also financed and sometimes took part in unofficial privateering expeditions against the Spaniards. A staunch Puritan, he became increasingly alienated from Court life and was associated with the opposition to the King's policies led by Lord Saye and Sele at Broughton Castle.

In March 1642, Parliament appointed Warwick Admiral of the Fleet against the King's wishes. His appointment ensured Parliament's control of the Navy. Even before the First Civil War broke out, Warwick's ships transferred arms and ammunition from the northern arsenal at Hull to London. Realising the strategic importance of control of the sea, the King attempted to dismiss Warwick from command but, with dissent from only two captains, the fleet accepted Warwick as Admiral and declared for Parliament in July 1642. Under Warwick's command, the Navy intercepted ships carrying supplies to the Royalists and supported military operations on land, notably at the siege of Hull in 1643 and Lyme 1644. In April 1645, however, Parliament decided to extend the Self-Denying Ordinance to include naval officers, and Warwick stepped down from his command. He was appointed chairman of the 12-man Admiralty Commission which replaced the office of Lord High Admiral.

In May 1648, just as the Second Civil War was erupting, the Fleet mutinied against the appointment of the Leveller Thomas Rainsborough as Admiral, and a number of warships defected to the Royalists. Warwick was re-appointed Admiral of the Fleet and sent to ensure the loyalty of the remaining ships. In August 1648, Warwick confronted a Royalist fleet commanded by the Prince of Wales in the shallow waters of the Thames estuary. The Prince avoided a battle and sailed back to Holland, with Warwick in pursuit. He blockaded the Royalists in the neutral Dutch port of Helvoetsluys, where Prince Rupert took over command. Unable to attack in neutral waters, Warwick maintained the blockade for several months, during which three of the Royalist ships defected back to Parliament. Reluctant to spend the winter off Helvoetsluys, Warwick returned to England with his entire fleet in November 1648. This allowed Rupert's fleet to escape to Kinsale in southern Ireland and begin raiding Commonwealth shipping.

The new republican government in England regarded Warwick's actions against the Royalists as over-cautious. His brother the Earl of Holland was at this time facing trial for fighting against Parliament in the Second Civil War. It was impossible to allow Warwick to retain control of the Navy. In February 1649, his commission was revoked and he was replaced by the three Generals-at-Sea Popham, Blake and Deane. Thereafter, Warwick retired from public life."

David Plant, British Civil Wars and Commonwealth website

http://www.british-civil-wars.co.…

Paul Chapin • Link

Self-Denying Ordinance

A bill passed by the House of Commons on 19 December 1644 stipulating that no member of the House of Commons or the House of Lords could hold any command in the army or navy. Since this meant that nobles were automatically debarred from military command (whereas members of the House of Commons could resign and retain their commands), the House of Lords hesitated, but finally passed the bill on 3 April 1645.

See http://www.british-civil-wars.co.… for further information.

Second Reading

Bill • Link

RICH, Sir ROBERT, second Earl of Warwick (1587-1658) eldest son of the first earl of Warwick and Penelope, Lady Rich, educated at Emmanuel College, Cambridge; K.B., 1603; member of the Inner Temple, 1604; M.P., Maldon, 1610 and 1614; succeeded his father in 1619, and occupied himself largely with the colonisation of America and with privateering ventures, which involved him in controversy with the great merchant companies; during the early part of Charles I's reign gradually became estranged from the court; was associated with the foundation of the colonies of New Plymouth, Massachusetts, and Connecticut; refused to subscribe to the forced loan of 1626 and to pay ship money, and protected the puritan clergy; arrested and his papers searched on the dissolution of the Short parliament, 1640; active in raising forces for parliament on the outbreak of civil war; gained the fleet, July 1642, and (1643) was appointed lord high admiral; nominated head of a commission for the government of the colonies, 1643; associated in 1644 with the foundation of Rhode Island; generally exerted his authority in behalf of religious freedom; endeavoured unsuccessfully (1648) to regain the fleet, the greater part of which had revolted to Charles I, but was able to organise a new one; after the abolition of the House of Lords was removed by the independents from the post of lord high admiral; took no part in public affairs during the Commonwealth, but received support and encouragement from Cromwell. His grandson, Robert Rich, married the Protector's daughter.

---Dictionary of National Biography: Index and Epitome. S. Lee, 1906.