Wikipedia

This text was copied from Wikipedia on 21 December 2024 at 3:10AM.

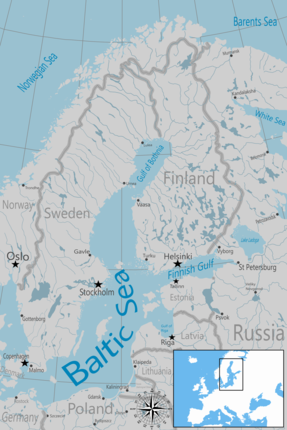

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the North and Central European Plain.[3]

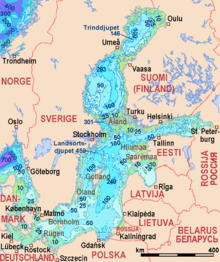

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from 10°E to 30°E longitude. It is a shelf sea and marginal sea of the Atlantic with limited water exchange between the two, making it an inland sea. The Baltic Sea drains through the Danish straits into the Kattegat by way of the Øresund, Great Belt and Little Belt. It includes the Gulf of Bothnia (divided into the Bothnian Bay and the Bothnian Sea), the Gulf of Finland, the Gulf of Riga and the Bay of Gdańsk.

The "Baltic Proper" is bordered on its northern edge, at latitude 60°N, by Åland and the Gulf of Bothnia, on its northeastern edge by the Gulf of Finland, on its eastern edge by the Gulf of Riga, and in the west by the Swedish part of the southern Scandinavian Peninsula.

The Baltic Sea is connected by artificial waterways to the White Sea via the White Sea–Baltic Canal and to the German Bight of the North Sea via the Kiel Canal.

Definitions

Administration

The Helsinki Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Area includes the Baltic Sea and the Kattegat, without calling Kattegat a part of the Baltic Sea, "For the purposes of this Convention the 'Baltic Sea Area' shall be the Baltic Sea and the Entrance to the Baltic Sea, bounded by the parallel of the Skaw in the Skagerrak at 57°44.43'N."[4]

Traffic history

Historically, the Kingdom of Denmark collected Sound Dues from ships at the border between the ocean and the land-locked Baltic Sea, in tandem: in the Øresund at Kronborg castle near Helsingør; in the Great Belt at Nyborg; and in the Little Belt at its narrowest part then Fredericia, after that stronghold was built. The narrowest part of Little Belt is the "Middelfart Sund" near Middelfart.[5]

Oceanography

Geographers widely agree that the preferred physical border between the Baltic and North Seas is the Langelandsbælt (the southern part of the Great Belt strait near Langeland) and the Drogden-Sill strait.[6] The Drogden Sill is situated north of Køge Bugt and connects Dragør in the south of Copenhagen to Malmö; it is used by the Øresund Bridge, including the Drogden Tunnel. By this definition, the Danish straits is part of the entrance, but the Bay of Mecklenburg and the Bay of Kiel are parts of the Baltic Sea. Another usual border is the line between Falsterbo, Sweden, and Stevns Klint, Denmark, as this is the southern border of Øresund. It is also the border between the shallow southern Øresund (with a typical depth of 5–10 meters only) and notably deeper water.

Hydrography and biology

Drogden Sill (depth of 7 m (23 ft)) sets a limit to Øresund and Darss Sill (depth of 18 m (59 ft)), and a limit to the Belt Sea.[7] The shallow sills are obstacles to the flow of heavy salt water from the Kattegat into the basins around Bornholm and Gotland.

The Kattegat and the southwestern Baltic Sea are well oxygenated and have a rich biology. The remainder of the Sea is brackish, poor in oxygen, and in species. Thus, statistically, the more of the entrance that is included in its definition, the healthier the Baltic appears; conversely, the more narrowly it is defined, the more endangered its biology appears.

Etymology and nomenclature

Tacitus called it the Suebic Sea, Latin: Mare Suebicum after the Germanic people of the Suebi,[8][9] and Ptolemy Sarmatian Ocean after the Sarmatians,[10] but the first to name it the Baltic Sea (Medieval Latin: Mare Balticum) was the eleventh-century German chronicler Adam of Bremen. The origin of the latter name is speculative and it was adopted into Slavic and Finnic languages spoken around the sea, very likely due to the role of Medieval Latin in cartography. It might be connected to the Germanic word belt, a name used for two of the Danish straits, the Belts, while others claim it to be directly derived from the source of the Germanic word, Latin balteus "belt".[11] Adam of Bremen himself compared the sea with a belt, stating that it is so named because it stretches through the land as a belt (Balticus, eo quod in modum baltei longo tractu per Scithicas regiones tendatur usque in Greciam).

He might also have been influenced by the name of a legendary island mentioned in the Natural History of Pliny the Elder. Pliny mentions an island named Baltia (or Balcia) with reference to accounts of Pytheas and Xenophon. It is possible that Pliny refers to an island named Basilia ("the royal") in On the Ocean by Pytheas. Baltia also might be derived from "belt", and therein mean "near belt of sea, strait".

Others have suggested that the name of the island originates from the Proto-Indo-European root *bʰel meaning "white, fair",[12] which may echo the naming of seas after colours relating to the cardinal points (as per Black Sea and Red Sea).[13] This '*bʰel' root and basic meaning were retained in Lithuanian (as baltas), Latvian (as balts) and Slavic (as bely). On this basis, a related hypothesis holds that the name originated from this Indo-European root via a Baltic language such as Lithuanian.[14] Another explanation is that, while derived from the aforementioned root, the name of the sea is related to names for various forms of water and related substances in several European languages, that might have been originally associated with colors found in swamps (compare Proto-Slavic *bolto "swamp"). Yet another explanation is that the name originally meant "enclosed sea, bay" as opposed to open sea.[15]

In the Middle Ages the sea was known by a variety of names. The name Baltic Sea became dominant after 1600. Usage of Baltic and similar terms to denote the region east of the sea started only in the 19th century.

Name in other languages

The Baltic Sea was known in ancient Latin language sources as Mare Suebicum or even Mare Germanicum.[16] Older native names in languages that used to be spoken on the shores of the sea or near it usually indicate the geographical location of the sea (in Germanic languages), or its size in relation to smaller gulfs (in Old Latvian), or tribes associated with it (in Old Russian the sea was known as the Varanghian Sea). In modern languages, it is known by the equivalents of "East Sea", "West Sea", or "Baltic Sea" in different languages:

- "Baltic Sea" is used in Modern English; in the Baltic languages Latvian (Baltijas jūra; in Old Latvian it was referred to as "the Big Sea", while the present day Gulf of Riga was referred to as "the Little Sea") and Lithuanian (Baltijos jūra); in Latin (Mare Balticum) and the Romance languages French (Mer Baltique), Italian (Mar Baltico), Portuguese (Mar Báltico), Romanian (Marea Baltică) and Spanish (Mar Báltico); in Greek (Βαλτική Θάλασσα Valtikí Thálassa); in Albanian (Deti Balltik); in Welsh (Môr Baltig); in the Slavic languages Polish (Morze Bałtyckie or Bałtyk), Czech (Baltské moře or Balt), Slovenian (Baltsko morje), Bulgarian (Балтийско море Baltijsko More), Kashubian (Bôłt), Macedonian (Балтичко Море Baltičko More), Ukrainian (Балтійське море Baltijs′ke More), Belarusian (Балтыйскае мора Baltyjskaje Mora), Russian (Балтийское море Baltiyskoye More) and Serbo-Croatian (Baltičko more / Балтичко море); in Hungarian (Balti-tenger).

- In Germanic languages, except English, "East Sea" is used, as in Afrikaans (Oossee), Danish (Østersøen [ˈøstɐˌsøˀn̩]), Dutch (Oostzee), German (Ostsee), Low German (Oostsee), Icelandic and Faroese (Eystrasalt), Norwegian (Bokmål: Østersjøen [ˈø̂stəˌʂøːn]; Nynorsk: Austersjøen), and Swedish (Östersjön). In Old English it was known as Ostsǣ,[17] which does not however mean 'east sea' and may be related to a people known in the same work as the Osti.[18] Also in Hungarian the former name was Keleti-tenger ("East-sea", due to German influence). In addition, Finnish, a Finnic language, uses the term Itämeri "East Sea", possibly a calque from a Germanic language. As the Baltic is not particularly eastward in relation to Finland, the use of this term may be a leftover from the period of Swedish rule.

- In another Finnic language, Estonian, it is called the "West Sea" (Läänemeri), with the correct geography (the sea is west of Estonia). In South Estonian, it has the meaning of both "West Sea" and "Evening Sea" (Õdagumeri). In the endangered Livonian language of Latvia, the sea (and sometimes the Irbe Strait as well) is called the "Large Sea" (Sūŗ meŗ or Sūr meŗ).[19][20]

History

Classical world

At the time of the Roman Empire, the Baltic Sea was known as the Mare Suebicum or Mare Sarmaticum. Tacitus in his AD 98 Agricola and Germania described the Mare Suebicum, named for the Suebi tribe, during the spring months, as a brackish sea where the ice broke apart and chunks floated about. The Suebi eventually migrated southwest to temporarily reside in the Rhineland area of modern Germany, where their name survives in the historic region known as Swabia. Jordanes called it the Germanic Sea in his work, the Getica.

Middle Ages

In the early Middle Ages, Norse (Scandinavian) merchants built a trade empire all around the Baltic. Later, the Norse fought for control of the Baltic against Wendish tribes dwelling on the southern shore. The Norse also used the rivers of Russia for trade routes, finding their way eventually to the Black Sea and southern Russia. This Norse-dominated period is referred to as the Viking Age.

Since the Viking Age, the Scandinavians have referred to the Baltic Sea as Austmarr ("Eastern Sea"). "Eastern Sea", appears in the Heimskringla and Eystra salt appears in Sörla þáttr. Saxo Grammaticus recorded in Gesta Danorum an older name, Gandvik, -vik being Old Norse for "bay", which implies that the Vikings correctly regarded it as an inlet of the sea. Another form of the name, "Grandvik", attested in at least one English translation of Gesta Danorum, is likely to be a misspelling.

In addition to fish the sea also provides amber, especially from its southern shores within today's borders of Poland, Russia and Lithuania. First mentions of amber deposits on the South Coast of the Baltic Sea date back to the 12th century.[21] The bordering countries have also traditionally exported lumber, wood tar, flax, hemp and furs by ship across the Baltic. Sweden had from early medieval times exported iron and silver mined there, while Poland had and still has extensive salt mines. Thus, the Baltic Sea has long been crossed by much merchant shipping.

The lands on the Baltic's eastern shore were among the last in Europe to be converted to Christianity. This finally happened during the Northern Crusades: Finland in the twelfth century by Swedes, and what are now Estonia and Latvia in the early thirteenth century by Danes and Germans (Livonian Brothers of the Sword). The Teutonic Order gained control over parts of the southern and eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, where they set up their monastic state. Lithuania was the last European state to convert to Christianity.

An arena of conflict

In the period between the 8th and 14th centuries, there was much piracy in the Baltic from the coasts of Pomerania and Prussia, and the Victual Brothers held Gotland.

Starting in the 11th century, the southern and eastern shores of the Baltic were settled by migrants mainly from Germany, a movement called the Ostsiedlung ("east settling"). Other settlers were from the Netherlands, Denmark, and Scotland. The Polabian Slavs were gradually assimilated by the Germans.[22] Denmark gradually gained control over most of the Baltic coast, until she lost much of her possessions after being defeated in the 1227 Battle of Bornhöved.

In the 13th to 16th centuries, the strongest economic force in Northern Europe was the Hanseatic League, a federation of merchant cities around the Baltic Sea and the North Sea. In the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, Poland, Denmark, and Sweden fought wars for Dominium maris baltici ("Lordship over the Baltic Sea"). Eventually, it was Sweden that virtually encompassed the Baltic Sea. In Sweden, the sea was then referred to as Mare Nostrum Balticum ("Our Baltic Sea"). The goal of Swedish warfare during the 17th century was to make the Baltic Sea an all-Swedish sea (Ett Svenskt innanhav), something that was accomplished except the part between Riga in Latvia and Stettin in Pomerania. However, the Dutch dominated the Baltic trade in the seventeenth century.

In the eighteenth century, Russia and Prussia became the leading powers over the sea. Sweden's defeat in the Great Northern War brought Russia to the eastern coast. Russia became and remained a dominating power in the Baltic. Russia's Peter the Great saw the strategic importance of the Baltic and decided to found his new capital, Saint Petersburg, at the mouth of the Neva river at the east end of the Gulf of Finland. There was much trading not just within the Baltic region but also with the North Sea region, especially eastern England and the Netherlands: their fleets needed the Baltic timber, tar, flax, and hemp.

During the Crimean War, a joint British and French fleet attacked the Russian fortresses in the Baltic; the case is also known as the Åland War. They bombarded Sveaborg, which guards Helsinki; and Kronstadt, which guards Saint Petersburg; and they destroyed Bomarsund in Åland. After the unification of Germany in 1871, the whole southern coast became German. World War I was partly fought in the Baltic Sea. After 1920 Poland was granted access to the Baltic Sea at the expense of Germany by the Polish Corridor and enlarged the port of Gdynia in rivalry with the port of the Free City of Danzig.

After the Nazis' rise to power, Germany reclaimed the Memelland and after the outbreak of the Eastern Front (World War II) occupied the Baltic states. In 1945, the Baltic Sea became a mass grave for retreating soldiers and refugees on torpedoed troop transports. The sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff remains the worst maritime disaster in history, killing (very roughly) 9,000 people. In 2005, a Russian group of scientists found over five thousand airplane wrecks, sunken warships, and other material, mainly from World War II, on the bottom of the sea.

Since World War II

Since the end of World War II, various nations, including the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and the United States have disposed of chemical weapons in the Baltic Sea, raising concerns of environmental contamination.[23] Today, fishermen occasionally find some of these materials: the most recent available report from the Helsinki Commission notes that four small scale catches of chemical munitions representing approximately 105 kg (231 lb) of material were reported in 2005. This is a reduction from the 25 incidents representing 1,110 kg (2,450 lb) of material in 2003.[24] Until now, the U.S. Government refuses to disclose the exact coordinates of the wreck sites. Deteriorating bottles leak mustard gas and other substances, thus slowly poisoning a substantial part of the Baltic Sea.

After 1945, the German population was expelled from all areas east of the Oder-Neisse line, making room for new Polish and Russian settlement. Poland gained most of the southern shore. The Soviet Union gained another access to the Baltic with the Kaliningrad Oblast, that had been part of German-settled East Prussia. The Baltic states on the eastern shore were annexed by the Soviet Union. The Baltic then separated opposing military blocs: NATO and the Warsaw Pact. Neutral Sweden developed incident weapons to defend its territorial waters after the Swedish submarine incidents.[25] This border status restricted trade and travel. It ended only after the collapse of the Communist regimes in Central and Eastern Europe in the late 1980s.

Finland and Sweden joined NATO in 2023 and 2024, respectively, making the Baltic Sea almost entirely surrounded by the alliance's members, leading some commentators to label the sea a ″NATO lake″.[26][27][28][29][30] Such an arrangement has also existed for the European Union (EU) since May 2004 following the accession of the Baltic states and Poland. The remaining non-NATO and non-EU shore areas are Russian: the Saint Petersburg area and the Kaliningrad Oblast exclave.

Storms and storm floods

Winter storms begin arriving in the region during October. These have caused numerous shipwrecks, and contributed to the extreme difficulties of rescuing passengers of the ferry M/S Estonia en route from Tallinn, Estonia, to Stockholm, Sweden, in September 1994, which claimed the lives of 852 people. Older, wood-based shipwrecks such as the Vasa tend to remain well-preserved, as the Baltic's cold and brackish water does not suit the shipworm.

Storm surge floods are generally taken to occur when the water level is more than one metre above normal. In Warnemünde about 110 floods occurred from 1950 to 2000, an average of just over two per year.[31]

Historic flood events were the All Saints' Flood of 1304 and other floods in the years 1320, 1449, 1625, 1694, 1784 and 1825. Little is known of their extent.[32] From 1872, there exist regular and reliable records of water levels in the Baltic Sea. The highest was the flood of 1872 when the water was an average of 2.43 m (8 ft 0 in) above sea level at Warnemünde and a maximum of 2.83 m (9 ft 3 in) above sea level in Warnemünde. In the last very heavy floods the average water levels reached 1.88 m (6 ft 2 in) above sea level in 1904, 1.89 m (6 ft 2 in) in 1913, 1.73 m (5 ft 8 in) in January 1954, 1.68 m (5 ft 6 in) on 2–4 November 1995 and 1.65 m (5 ft 5 in) on 21 February 2002.[33]

Geography

Geophysical data

An arm of the North Atlantic Ocean, the Baltic Sea is enclosed by Sweden and Denmark to the west, Finland to the northeast, and the Baltic countries to the southeast.

It is about 1,600 km (990 mi) long, an average of 193 km (120 mi) wide, and an average of 55 metres (180 ft) deep. The maximum depth is 459 m (1,506 ft) which is on the Swedish side of the center. The surface area is about 349,644 km2 (134,998 sq mi) [34] and the volume is about 20,000 km3 (4,800 cu mi). The periphery amounts to about 8,000 km (5,000 mi) of coastline.[35]

The Baltic Sea is one of the largest brackish inland seas by area, and occupies a basin (a Zungenbecken) formed by glacial erosion during the last few ice ages.

| Sub-area | Area | Volume | Maximum depth | Average depth | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | sq mi | km3 | cu mi | m | ft | m | ft | |

| Baltic proper | 211,069 | 81,494 | 13,045 | 3,130 | 459 | 1,506 | 62.1 | 204 |

| Gulf of Bothnia | 115,516 | 44,601 | 6,389 | 1,533 | 230 | 750 | 60.2 | 198 |

| Gulf of Finland | 29,600 | 11,400 | 1,100 | 260 | 123 | 404 | 38.0 | 124.7 |

| Gulf of Riga | 16,300 | 6,300 | 424 | 102 | 60 | 200 | 26.0 | 85.3 |

| Belt Sea/Kattegat | 42,408 | 16,374 | 802 | 192 | 109 | 358 | 18.9 | 62 |

| Total Baltic Sea | 415,266 | 160,335 | 21,721 | 5,211 | 459 | 1,506 | 52.3 | 172 |

Extent

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the limits of the Baltic Sea as follows:[37]

- Bordered by the coasts of Germany, Denmark, Poland, Sweden, Finland, Russia, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, it extends north-eastward of the following limits:

- In the Little Belt. A line joining Falshöft (54°47′N 9°57.5′E / 54.783°N 9.9583°E / 54.783; 9.9583) and Vejsnæs Nakke (Ærø: 54°49′N 10°26′E / 54.817°N 10.433°E / 54.817; 10.433).

- In the Great Belt. A line joining Gulstav (South extreme of Langeland Island) and Kappel Kirke (54°46′N 11°01′E / 54.767°N 11.017°E / 54.767; 11.017) on Island of Lolland.

- In the Guldborg Sound. A line joining Flinthorne-Rev and Skjelby (54°38′N 11°53′E / 54.633°N 11.883°E / 54.633; 11.883).

- In the Sound. A line joining Stevns Lighthouse (55°17′N 12°27′E / 55.283°N 12.450°E / 55.283; 12.450) and Falsterbo Point (55°23′N 12°49′E / 55.383°N 12.817°E / 55.383; 12.817).

Subdivisions

1 = Bothnian Bay

2 = Bothnian Sea

1 + 2 = Gulf of Bothnia, partly also 3 & 4

3 = Archipelago Sea

4 = Åland Sea

5 = Gulf of Finland

6 = Northern Baltic Proper

7 = Western Gotland Basin

8 = Eastern Gotland Basin

9 = Gulf of Riga

10 = Bay of Gdańsk/Gdansk Basin

11 = Bornholm Basin and Hanö Bight

12 = Arkona Basin

6–12 = Baltic Proper

13 = Kattegat, not an integral part of the Baltic Sea

14 = Belt Sea (Little Belt and Great Belt)

15 = Öresund (The Sound)

14 + 15 = Danish straits, not an integral part of the Baltic Sea

The northern part of the Baltic Sea is known as the Gulf of Bothnia, of which the northernmost part is the Bay of Bothnia or Bothnian Bay. The more rounded southern basin of the gulf is called Bothnian Sea and immediately to the south of it lies the Sea of Åland. The Gulf of Finland connects the Baltic Sea with Saint Petersburg. The Gulf of Riga lies between the Latvian capital city of Riga and the Estonian island of Saaremaa.

The Northern Baltic Sea lies between the Stockholm area, southwestern Finland, and Estonia. The Western and Eastern Gotland basins form the major parts of the Central Baltic Sea or Baltic proper. The Bornholm Basin is the area east of Bornholm, and the shallower Arkona Basin extends from Bornholm to the Danish isles of Falster and Zealand.

In the south, the Bay of Gdańsk lies east of the Hel Peninsula on the Polish coast and west of the Sambia Peninsula in Kaliningrad Oblast. The Bay of Pomerania lies north of the islands of Usedom/Uznam and Wolin, east of Rügen. Between Falster and the German coast lie the Bay of Mecklenburg and Bay of Lübeck. The westernmost part of the Baltic Sea is the Bay of Kiel. The three Danish straits, the Great Belt, the Little Belt and The Sound (Öresund/Øresund), connect the Baltic Sea with the Kattegat and Skagerrak strait in the North Sea.

Temperature and ice

The water temperature of the Baltic Sea varies significantly depending on exact location, season and depth. At the Bornholm Basin, which is located directly east of the island of the same name, the surface temperature typically falls to 0–5 °C (32–41 °F) during the peak of the winter and rises to 15–20 °C (59–68 °F) during the peak of the summer, with an annual average of around 9–10 °C (48–50 °F).[39] A similar pattern can be seen in the Gotland Basin, which is located between the island of Gotland and Latvia. In the deep of these basins the temperature variations are smaller. At the bottom of the Bornholm Basin, deeper than 80 m (260 ft), the temperature typically is 1–10 °C (34–50 °F), and at the bottom of the Gotland Basin, at depths greater than 225 m (738 ft), the temperature typically is 4–7 °C (39–45 °F).[39] Generally, offshore locations, lower latitudes and islands maintain maritime climates, but adjacent to the water continental climates are common, especially on the Gulf of Finland. In the northern tributaries the climates transition from moderate continental to subarctic on the northernmost coastlines.

On the long-term average, the Baltic Sea is ice-covered at the annual maximum for about 45% of its surface area. The ice-covered area during such a typical winter includes the Gulf of Bothnia, the Gulf of Finland, the Gulf of Riga, the archipelago west of Estonia, the Stockholm archipelago, and the Archipelago Sea southwest of Finland. The remainder of the Baltic does not freeze during a normal winter, except sheltered bays and shallow lagoons such as the Curonian Lagoon. The ice reaches its maximum extent in February or March; typical ice thickness in the northernmost areas in the Bothnian Bay, the northern basin of the Gulf of Bothnia, is about 70 cm (28 in) for landfast sea ice. The thickness decreases farther south.

Freezing begins in the northern extremities of the Gulf of Bothnia typically in the middle of November, reaching the open waters of the Bothnian Bay in early January. The Bothnian Sea, the basin south of Kvarken, freezes on average in late February. The Gulf of Finland and the Gulf of Riga freeze typically in late January. In 2011, the Gulf of Finland was completely frozen on 15 February.[40]

The ice extent depends on whether the winter is mild, moderate, or severe. In severe winters ice can form around southern Sweden and even in the Danish straits. According to the 18th-century natural historian William Derham, during the severe winters of 1703 and 1708, the ice cover reached as far as the Danish straits.[41] Frequently, parts of the Gulf of Bothnia and the Gulf of Finland are frozen, in addition to coastal fringes in more southerly locations such as the Gulf of Riga. This description meant that the whole of the Baltic Sea was covered with ice.

Since 1720, the Baltic Sea has frozen over entirely 20 times, most recently in early 1987, which was the most severe winter in Scandinavia since 1720. The ice then covered 400,000 km2 (150,000 sq mi). During the winter of 2010–11, which was quite severe compared to those of the last decades, the maximum ice cover was 315,000 km2 (122,000 sq mi), which was reached on 25 February 2011. The ice then extended from the north down to the northern tip of Gotland, with small ice-free areas on either side, and the east coast of the Baltic Sea was covered by an ice sheet about 25 to 100 km (16 to 62 mi) wide all the way to Gdańsk. This was brought about by a stagnant high-pressure area that lingered over central and northern Scandinavia from around 10 to 24 February. After this, strong southern winds pushed the ice further into the north, and much of the waters north of Gotland were again free of ice, which had then packed against the shores of southern Finland.[42] The effects of the afore-mentioned high-pressure area did not reach the southern parts of the Baltic Sea, and thus the entire sea did not freeze over. However, floating ice was additionally observed near Świnoujście harbor in January 2010.

In recent years before 2011, the Bothnian Bay and the Bothnian Sea were frozen with solid ice near the Baltic coast and dense floating ice far from it. In 2008, almost no ice formed except for a short period in March.[43]

During winter, fast ice, which is attached to the shoreline, develops first, rendering ports unusable without the services of icebreakers. Level ice, ice sludge, pancake ice, and rafter ice form in the more open regions. The gleaming expanse of ice is similar to the Arctic, with wind-driven pack ice and ridges up to 15 m (49 ft). Offshore of the landfast ice, the ice remains very dynamic all year, and it is relatively easily moved around by winds and therefore forms pack ice, made up of large piles and ridges pushed against the landfast ice and shores.

In spring, the Gulf of Finland and the Gulf of Bothnia normally thaw in late April, with some ice ridges persisting until May in the eastern extremities of the Gulf of Finland. In the northernmost reaches of the Bothnian Bay, ice usually stays until late May; by early June it is practically always gone. However, in the famine year of 1867 remnants of ice were observed as late as 17 July near Uddskär.[44] Even as far south as Øresund, remnants of ice have been observed in May on several occasions; near Taarbaek on 15 May 1942 and near Copenhagen on 11 May 1771. Drift ice was also observed on 11 May 1799.[45][46][47]

The ice cover is the main habitat for two large mammals, the grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) and the Baltic ringed seal (Pusa hispida botnica), both of which feed underneath the ice and breed on its surface. Of these two seals, only the Baltic ringed seal suffers when there is not adequate ice in the Baltic Sea, as it feeds its young only while on ice. The grey seal is adapted to reproducing also with no ice in the sea. The sea ice also harbors several species of algae that live in the bottom and inside unfrozen brine pockets in the ice.

Due to the often fluctuating winter temperatures between above and below freezing, the saltwater ice of the Baltic Sea can be treacherous and hazardous to walk on, in particular in comparison to the more stable fresh water-ice sheets in the interior lakes.

Hydrography

The Baltic Sea flows out through the Danish straits; however, the flow is complex. A surface layer of brackish water discharges 940 km3 (230 cu mi) per year into the North Sea. Due to the difference in salinity, by salinity permeation principle, a sub-surface layer of more saline water moving in the opposite direction brings in 475 km3 (114 cu mi) per year. It mixes very slowly with the upper waters, resulting in a salinity gradient from top to bottom, with most of the saltwater remaining below 40 to 70 m (130 to 230 ft) deep. The general circulation is anti-clockwise: northwards along its eastern boundary, and south along with the western one .[48]

The difference between the outflow and the inflow comes entirely from fresh water. More than 250 streams drain a basin of about 1,600,000 km2 (620,000 sq mi), contributing a volume of 660 km3 (160 cu mi) per year to the Baltic. They include the major rivers of north Europe, such as the Oder, the Vistula, the Neman, the Daugava and the Neva. Additional fresh water comes from the difference of precipitation less evaporation, which is positive.

An important source of salty water is infrequent inflows (also known as major Baltic inflows or MBIs) of North Sea water into the Baltic. Such inflows, important to the Baltic ecosystem because of the oxygen they transport into the Baltic deeps, happen on average once per year, but large pulses that can replace the anoxic deep water in the Gotland Deep occur about once in ten years. Previously, it was believed that the frequency of MBIs had declined since 1980, but recent studies have challenged this view and no longer display a clear change in the frequency or intensity of saline inflows. Instead, a decadal variability in the intensities of MBIs is observed with a main period of approximately 30 years.[49][50]

The water level is generally far more dependent on the regional wind situation than on tidal effects. However, tidal currents occur in narrow passages in the western parts of the Baltic Sea. Tides can reach 17 to 19 cm (6.7 to 7.5 in) in the Gulf of Finland.[51]

The significant wave height is generally much lower than that of the North Sea. Quite violent, sudden storms sweep the surface ten or more times a year, due to large transient temperature differences and a long reach of the wind. Seasonal winds also cause small changes in sea level, of the order of 0.5 m (1 ft 8 in) .[48] According to the media, during a storm in January 2017, an extreme wave above 14 m (46 ft) has been measured and significant wave height of around 8 m (26 ft) has been measured by the FMI. A numerical study has shown the presence of events with 8 to 10 m (26 to 33 ft) significant wave heights. Those extreme waves events can play an important role in the coastal zone on erosion and sea dynamics.[52]

Salinity

The Baltic Sea is the world's largest brackish sea.[53] Only two other brackish waters are larger according to some measurements: The Black Sea is larger in both surface area and water volume, but most of it is located outside the continental shelf (only a small fraction is inland). The Caspian Sea is larger in water volume, but—despite its name—it is a lake rather than a sea.[53]

The Baltic Sea's salinity is much lower than that of ocean water (which averages 3.5%), as a result of abundant freshwater runoff from the surrounding land (rivers, streams and alike), combined with the shallowness of the sea itself; runoff contributes roughly one-fortieth its total volume per year, as the volume of the basin is about 21,000 km3 (5,000 cu mi) and yearly runoff is about 500 km3 (120 cu mi).

The open surface waters of the Baltic Sea "proper" generally have a salinity of 0.3 to 0.9%, which is border-line freshwater. The flow of freshwater into the sea from approximately two hundred rivers and the introduction of salt from the southwest builds up a gradient of salinity in the Baltic Sea. The highest surface salinities, generally 0.7–0.9%, are in the southwesternmost part of the Baltic, in the Arkona and Bornholm basins (the former located roughly between southeast Zealand and Bornholm, and the latter directly east of Bornholm). It gradually falls further east and north, reaching the lowest in the Bothnian Bay at around 0.3%.[54] Drinking the surface water of the Baltic as a means of survival would actually hydrate the body instead of dehydrating, as is the case with ocean water.[note 1]

As saltwater is denser than freshwater, the bottom of the Baltic Sea is saltier than the surface. This creates a vertical stratification of the water column, a halocline, that represents a barrier to the exchange of oxygen and nutrients, and fosters completely separate maritime environments.[55] The difference between the bottom and surface salinities varies depending on location. Overall it follows the same southwest to east and north pattern as the surface. At the bottom of the Arkona Basin (equalling depths greater than 40 m or 130 ft) and Bornholm Basin (depths greater than 80 m or 260 ft) it is typically 1.4–1.8%. Further east and north the salinity at the bottom is consistently lower, being the lowest in Bothnian Bay (depths greater than 120 m or 390 ft) where it is slightly below 0.4%, or only marginally higher than the surface in the same region.[54]

In contrast, the salinity of the Danish straits, which connect the Baltic Sea and Kattegat, tends to be significantly higher, but with major variations from year to year. For example, the surface and bottom salinity in the Great Belt is typically around 2.0% and 2.8% respectively, which is only somewhat below that of the Kattegat.[54] The water surplus caused by the continuous inflow of rivers and streams to the Baltic Sea means that there generally is a flow of brackish water out through the Danish straits to the Kattegat (and eventually the Atlantic).[56] Significant flows in the opposite direction, salt water from the Kattegat through the Danish straits to the Baltic Sea, are less regular and are known as major Baltic inflows (MBIs).

Major tributaries

The rating of mean discharges differs from the ranking of hydrological lengths (from the most distant source to the sea) and the rating of the nominal lengths. Göta älv, a tributary of the Kattegat, is not listed, as due to the northward upper low-salinity-flow in the sea, its water hardly reaches the Baltic proper:

| Name | Mean discharge | Length | Basin area | States sharing the basin | Longest watercourse | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m3/s | cu ft/s | km | mi | km2 | sq mi | |||

| Neva (nominal) | 2,500 | 88,000 | 74 | 46 | 281,000 | 108,000 | Russia, Finland (Ladoga-affluent Vuoksi) | Suna (280 km; 170 mi) → Lake Onega (160 km; 99 mi) → Svir (224 km; 139 mi) → Lake Ladoga (122 km; 76 mi) → Neva |

| Neva (hydrological) | 2,500 | 88,000 | 860 | 530 | 281,000 | 108,000 | ||

| Vistula | 1,080 | 38,000 | 1,047 | 651 | 194,424 | 75,068 | Poland, tributaries: Belarus, Ukraine, Slovakia | Bug (774 km; 481 mi) → Narew (22 km; 14 mi) → Vistula (156 km; 97 mi) total 1204 km; 127 mi |

| Daugava | 678 | 23,900 | 1,020 | 630 | 87,900 | 33,900 | Russia (source), Belarus, Latvia | |

| Neman | 678 | 23,900 | 937 | 582 | 98,200 | 37,900 | Belarus (source), Lithuania, Russia | |

| Kemijoki (main river) | 556 | 19,600 | 550 | 340 | 51,127 | 19,740 | Finland, Norway (source of Ounasjoki) | longer tributary Kitinen |

| Kemijoki (river system) | 556 | 19,600 | 600 | 370 | 51,127 | 19,740 | ||

| Oder | 540 | 19,000 | 866 | 538 | 118,861 | 45,892 | Czech Republic (source), Poland, Germany | Warta (808 km; 502 mi) → Oder (180 km; 110 mi) total: 928 km; 577 mi |

| Lule älv | 506 | 17,900 | 461 | 286 | 25,240 | 9,750 | Sweden | |

| Narva (nominal) | 415 | 14,700 | 77 | 48 | 56,200 | 21,700 | Russia (source of Velikaya), Estonia | Velikaya (430 km; 270 mi) → Lake Peipus (145 km; 90 mi) → Narva |

| Narva (hydrological) | 415 | 14,700 | 652 | 405 | 56,200 | 21,700 | ||

| Torne älv (nominal) | 388 | 13,700 | 520 | 320 | 40,131 | 15,495 | Norway (source), Sweden, Finland | Válfojohka → Kamajåkka → Abiskojaure → Abiskojokk (total 40 km; 25 mi) → Torneträsk (70 km; 43 mi) → Torne älv |

| Torne älv (hydrological) | 388 | 13,700 | 630 | 390 | 40,131 | 15,495 | ||

Islands and archipelagoes

- Åland (Finland, autonomous)

- Archipelago Sea (Finland)

- Blekinge archipelago (Sweden)

- Bornholm, including Christiansø (Denmark)

- Falster (Denmark)

- Gotland (Sweden)

- Hailuoto (Finland)

- Kotlin (Russia)

- Lolland (Denmark)

- Kvarken archipelago, including Valsörarna (Finland)

- Møn (Denmark)

- Öland (Sweden)

- Rügen (Germany)

- Stockholm archipelago (Sweden)

- Usedom or Uznam (split between Germany and Poland)

- West Estonian archipelago (Estonia):

- Wolin (Poland)

- Zealand (Denmark)

Coastal countries

Countries that border the sea: Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden.

Countries lands in the outer drainage basin: Belarus, Czech Republic, Norway, Slovakia, Ukraine.

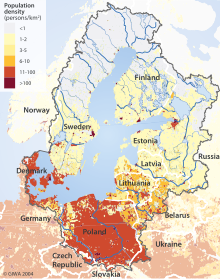

The Baltic Sea drainage basin is roughly four times the surface area of the sea itself. About 48% of the region is forested, with Sweden and Finland containing the majority of the forest, especially around the Gulfs of Bothnia and Finland.

About 20% of the land is used for agriculture and pasture, mainly in Poland and around the edge of the Baltic Proper, in Germany, Denmark, and Sweden. About 17% of the basin is unused open land with another 8% of wetlands. Most of the latter are in the Gulfs of Bothnia and Finland.

The rest of the land is heavily populated. About 85 million people live in the Baltic drainage basin, 15 million within 10 km (6 mi) of the coast and 29 million within 50 km (31 mi) of the coast. Around 22 million live in population centers of over 250,000. 90% of these are concentrated in the 10 km (6 mi) band around the coast. Of the nations containing all or part of the basin, Poland includes 45% of the 85 million, Russia 12%, Sweden 10% and the others less than 6% each.[57]

Cities

The biggest coastal cities (by population):

- Saint Petersburg (Russia) 5,392,992 (metropolitan area 6,000,000)

- Stockholm (Sweden) 962,154 (metropolitan area 2,315,612)

- Helsinki (Finland) 665,558 (metropolitan area 1,559,558)

- Riga (Latvia) 614,618 (metropolitan area 1,070,00)

- Gdańsk (Poland) 462,700 (metropolitan area 1,041,000)

- Tallinn (Estonia) 458,398 (metropolitan area 542,983)

- Kaliningrad (Russia) 431,500

- Szczecin (Poland) 413,600 (metropolitan area 778,000)

- Espoo (Finland) 306,792 (part of Helsinki metropolitan area)

- Gdynia (Poland) 255,600 (metropolitan area 1,041,000)

- Kiel (Germany) 247,000[58]

- Lübeck (Germany) 216,100

- Rostock (Germany) 212,700

- Klaipėda (Lithuania) 194,400

- Oulu (Finland) 191,050

- Turku (Finland) 180,350

Other important ports:

- Estonia:

- Finland:

- Germany:

- Flensburg 94,000

- Stralsund 58,000

- Greifswald 55,000

- Wismar 44,000

- Eckernförde 22,000

- Neustadt in Holstein 16,000

- Wolgast 12,000

- Sassnitz 10,000

- Latvia:

- Lithuania:

- Palanga 17,000

- Poland:

- Kołobrzeg 44,800

- Świnoujście 41,500

- Police 34,284

- Władysławowo 15,000

- Darłowo 14,000

- Russia:

- Sweden:

- Norrköping 84,000

- Gävle 75,451

- Trelleborg 26,000

- Karlshamn 19,000

- Oxelösund 11,000

Geology

| Evolution of the Baltic Sea |

|---|

| Pleistocene |

|

Eemian Sea (130,000–115,000 BCE) Ice sheets and seas (115,000–14,000 BCE) |

| Holocene |

|

Baltic Ice Lake (14,000–9,670 BCE) Yoldia Sea (9,670–8,750 BCE) Ancylus Lake (8,750–7,850 BCE) Mastogloia Sea (Initial Littorina Sea} (7,850–6,550 BCE) Littorina Sea (6,550–2,050 BCE) Modern Baltic Sea (2,050 BCE–present) |

| Sources. Dates are not BP. |

The Baltic Sea somewhat resembles a riverbed, with two tributaries, the Gulf of Finland and Gulf of Bothnia. Geological surveys show that before the Pleistocene, instead of the Baltic Sea, there was a wide plain around a great river that paleontologists call the Eridanos. Several Pleistocene glacial episodes scooped out the river bed into the sea basin. By the time of the last, or Eemian Stage (MIS 5e), the Eemian Sea was in place. Instead of a true sea, the Baltic can even today also be understood as the common estuary of all rivers flowing into it.

From that time the waters underwent a geologic history summarized under the names listed below. Many of the stages are named after marine animals (e.g. the Littorina mollusk) that are clear markers of changing water temperatures and salinity.

The factors that determined the sea's characteristics were the submergence or emergence of the region due to the weight of ice and subsequent isostatic readjustment, and the connecting channels it found to the North Sea-Atlantic, either through the straits of Denmark or at what are now the large lakes of Sweden, and the White Sea-Arctic Sea. There are a number of named and dated stages in the evolution of the Baltic Sea:[59]

- Eemian Sea, about 130,000–115,000 years BP

- Baltic Ice Lake, 16,000–11,700 years cal. BP

- Yoldia Sea, 11,700–10,700 years cal. BP

- Ancylus Lake, 10,700–9,800 years cal. BP

- Mastogloia Sea, 9,800–8,500 years cal. BP

- Littorina Sea, 8,500–4,000 years cal. BP

- Post-Littorina Sea, 4,000–present

The land is still emerging isostatically from its depressed state, which was caused by the weight of ice during the last glaciation. The phenomenon is known as post-glacial rebound. Consequently, the surface area and the depth of the sea are diminishing. The uplift is about eight millimeters per year on the Finnish coast of the northernmost Gulf of Bothnia. In the area, the former seabed is only gently sloping, leading to large areas of land being reclaimed in what are, geologically speaking, relatively short periods (decades and centuries).

The "Baltic Sea anomaly"

The "Baltic Sea anomaly" is a feature on an indistinct sonar image taken by Swedish salvage divers on the floor of the northern Baltic Sea in June 2011. The treasure hunters suggested the image showed an object with unusual features of seemingly extraordinary origin. Speculation published in tabloid newspapers claimed that the object was a sunken UFO. A consensus of experts and scientists say that the image most likely shows a natural geological formation.[60][61][62][63][64]

Biology

Fauna and flora

The fauna of the Baltic Sea is a mixture of marine and freshwater species. Among marine fishes are Atlantic cod, Atlantic herring, European hake, European plaice, European flounder, shorthorn sculpin and turbot, and examples of freshwater species include European perch, northern pike, whitefish and common roach. Freshwater species may occur at outflows of rivers or streams in all coastal sections of the Baltic Sea. Otherwise, marine species dominate in most sections of the Baltic, at least as far north as Gävle, where less than one-tenth are freshwater species. Further north the pattern is inverted. In the Bothnian Bay, roughly two-thirds of the species are freshwater. In the far north of this bay, saltwater species are almost entirely absent.[39] For example, the common starfish and shore crab, two species that are very widespread along European coasts, are both unable to cope with the significantly lower salinity. Their range limit is west of Bornholm, meaning that they are absent from the vast majority of the Baltic Sea.[39] Some marine species, like the Atlantic cod and European flounder, can survive at relatively low salinities but need higher salinities to breed, which therefore occurs in deeper parts of the Baltic Sea.[65][66] The common blue mussel is the dominating animal species, and makes up more than 90% of the total animal biomass in the sea.[67]

There is a decrease in species richness from the Danish belts to the Gulf of Bothnia. The decreasing salinity along this path causes restrictions in both physiology and habitats.[68] At more than 600 species of invertebrates, fish, aquatic mammals, aquatic birds and macrophytes, the Arkona Basin (roughly between southeast Zealand and Bornholm) is far richer than other more eastern and northern basins in the Baltic Sea, which all have less than 400 species from these groups, with the exception of the Gulf of Finland with more than 750 species. However, even the most diverse sections of the Baltic Sea have far fewer species than the almost-full saltwater Kattegat, which is home to more than 1600 species from these groups.[39] The lack of tides has affected the marine species as compared with the Atlantic.

Since the Baltic Sea is so young there are only two or three known endemic species: the brown alga Fucus radicans and the flounder Platichthys solemdali. Both appear to have evolved in the Baltic basin and were only recognized as species in 2005 and 2018 respectively, having formerly been confused with more widespread relatives.[66][69] The tiny Copenhagen cockle (Parvicardium hauniense), a rare mussel, is sometimes considered endemic, but has now been recorded in the Mediterranean.[70] However, some consider non-Baltic records to be misidentifications of juvenile lagoon cockles (Cerastoderma glaucum).[71] Several widespread marine species have distinctive subpopulations in the Baltic Sea adapted to the low salinity, such as the Baltic Sea forms of the Atlantic herring and lumpsucker, which are smaller than the widespread forms in the North Atlantic.[56]

A peculiar feature of the fauna is that it contains a number of glacial relict species, isolated populations of arctic species which have remained in the Baltic Sea since the last glaciation, such as the large isopod Saduria entomon, the Baltic subspecies of ringed seal, and the fourhorn sculpin. Some of these relicts are derived from glacial lakes, such as Monoporeia affinis, which is a main element in the benthic fauna of the low-salinity Bothnian Bay.

Cetaceans in the Baltic Sea are monitored by the countries bordering the sea and data compiled by various intergovernmental bodies, such as ASCOBANS. A critically endangered population of harbor porpoise inhabit the Baltic proper, whereas the species is abundant in the outer Baltic (Western Baltic and Danish straits) and occasionally oceanic and out-of-range species such as minke whales,[72] bottlenose dolphins,[73] beluga whales,[74] orcas,[75] and beaked whales[76] visit the waters. In recent years, very small, but with increasing rates, fin whales[77][78][79][80] and humpback whales migrate into Baltic sea including mother and calf pair.[81] Now extinct Atlantic grey whales (remains found from Gräsö along Bothnian Sea/southern Bothnian Gulf[82] and Ystad[83]) and eastern population of North Atlantic right whales that is facing functional extinction[84] once migrated into Baltic Sea.[85]

Other notable megafauna include the basking sharks.[86]

Environmental status

Satellite images taken in July 2010 revealed a massive algal bloom covering 377,000 square kilometres (146,000 sq mi) in the Baltic Sea. The area of the bloom extended from Germany and Poland to Finland. Researchers of the phenomenon have indicated that algal blooms have occurred every summer for decades. Fertilizer runoff from surrounding agricultural land has exacerbated the problem and led to increased eutrophication.[87]

Approximately 100,000 km2 (38,610 sq mi) of the Baltic's seafloor (a quarter of its total area) is a variable dead zone. The more saline (and therefore denser) water remains on the bottom, isolating it from surface waters and the atmosphere. This leads to decreased oxygen concentrations within the zone. It is mainly bacteria that grow in it, digesting organic material and releasing hydrogen sulfide. Because of this large anaerobic zone, the seafloor ecology differs from that of the neighboring Atlantic.

Plans to artificially oxygenate areas of the Baltic that have experienced eutrophication have been proposed by the University of Gothenburg and Inocean AB. The proposal intends to use wind-driven pumps to pump oxygen-rich surface water to a depth of around 130 m.[88]

After World War II, Germany had to be disarmed and large quantities of ammunition stockpiles were disposed directly into the Baltic Sea and the North Sea. Environmental experts and marine biologists warn that these ammunition dumps pose an environmental threat with potentially life-threatening consequences to the health and safety of humans on the coastlines of these seas.[89]

Future change

Climate change, and pollution from agriculture and forestry, impose such strong effects on the ecosystems of the Baltic sea, that there is a concern the sea will turn from a carbon sink to a source of CO2 and methane.[90] Modelling climate change and the impact of well characterised factors such as post-glacial rebound before the year 2050, is complicated by the unique properties of the Baltic Sea area compared to say the adjacent North Sea and contraversy as to the relative contributions of socio-ecomonic factors such as land use to any warming component.[91]: 537 These include its current brackish water, the southern subbasin tendency to have a vertical stratification of the halocline, and the northen subbasin seasonal sea ice cover.[91]: 458 High confidence future projections include: air temperature warming, more heavy precipitation episodes, less snow with less perifrost and glacial ice mass in northern catchment areas, more mild winters, raised mean water temperature with more marine heatwaves, intensified seasonal thermoclines without change in the thermohaline circulation, and sea level rise.[91]: 547, 458–9 There are many more projections but these have lower confidence.[91]: 547, 458–9 [note 2]

Economy

Construction of the Great Belt Bridge in Denmark (completed 1997) and the Øresund Bridge-Tunnel (completed 1999), linking Denmark with Sweden, provided a highway and railroad connection between Sweden and the Danish mainland (the Jutland Peninsula, precisely the Zealand). The undersea tunnel of the Øresund Bridge-Tunnel provides for navigation of large ships into and out of the Baltic Sea. The Baltic Sea is the main trade route for the export of Russian petroleum. Many of the countries neighboring the Baltic Sea have been concerned about this since a major oil leak in a seagoing tanker would be disastrous for the Baltic—given the slow exchange of water. The tourism industry surrounding the Baltic Sea is naturally concerned about oil pollution.

Much shipbuilding is carried out in the shipyards around the Baltic Sea. The largest shipyards are at Gdańsk, Gdynia, and Szczecin, Poland; Kiel, Germany; Karlskrona and Malmö, Sweden; Rauma, Turku, and Helsinki, Finland; Riga, Ventspils, and Liepāja, Latvia; Klaipėda, Lithuania; and Saint Petersburg, Russia.

There are several cargo and passenger ferries that operate on the Baltic Sea, such as Scandlines, Silja Line, Polferries, the Viking Line, Tallink, and Superfast Ferries.

Construction of the Fehmarn Belt Fixed Link between Denmark and Germany is due to finish in 2029. It will be a three-bore tunnel carrying four motorway lanes and two rail tracks.

Through the development of offshore wind power the Baltic Sea is expected to become a major source of energy for countries in the region. According to the Marienborg Declaration, signed in 2022, all EU Baltic Sea states have announced their intentions to have 19.6 gigawatts of offshore wind in operation by 2030.[92]

Tourism

|

Piers

|

Resort towns

|

The Helsinki Convention

1974 Convention

For the first time ever, all the sources of pollution around an entire sea were made subject to a single convention, signed in 1974 by the then seven Baltic coastal states. The 1974 Convention entered into force on 3 May 1980.

1992 Convention

In the light of political changes and developments in international environmental and maritime law, a new convention was signed in 1992 by all the states bordering on the Baltic Sea, and the European Community. After ratification, the Convention entered into force on 17 January 2000. The Convention covers the whole of the Baltic Sea area, including inland waters and the water of the sea itself, as well as the seabed. Measures are also taken in the whole catchment area of the Baltic Sea to reduce land-based pollution. The convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Area, 1992, entered into force on 17 January 2000.

The governing body of the convention is the Helsinki Commission,[93] also known as HELCOM, or Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission. The present contracting parties are Denmark, Estonia, the European Community, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, and Sweden.

The ratification instruments were deposited by the European Community, Germany, Latvia and Sweden in 1994, by Estonia and Finland in 1995, by Denmark in 1996, by Lithuania in 1997, and by Poland and Russia in November 1999.

See also

Notes

- ^ A healthy serum concentration of sodium is around 0.8–0.85%, and healthy kidneys can concentrate salt in urine to at least 1.4%.

- ^ All future projections have limits and make assumptions. The cause of the Younger Dryas which impacted on the Baltic area is unknown and such an event is not considered in most Baltic Sea future modelling.

References

- ^ "Coalition Clean Baltic". Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ^ Gunderson, Lance H.; Pritchard, Lowell (1 October 2002). Resilience and the Behavior of Large-Scale Systems. Island Press. ISBN 9781559639712 – via Google Books.

- ^ Niktalab, Poopak (2024). Over the Alps: History of Children and Youth Literature in Europe (in Persian) (1st ed.). Tehran, Iran: Faradid Publisher. p. 6. ISBN 9786225740457.

- ^ "Text of Helsinki Convention". Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ^ "Sundzoll". Academic dictionaries and encyclopedias. Archived from the original on 2 October 2022. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ "Fragen zum Meer (Antworten) – IOW". www.io-warnemuende.de. Archived from the original on 20 April 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ^ "Swedish Chemicals Agency (KEMI): The BaltSens Project – The sensitivity of the Baltic Sea ecosystems to hazardous compounds" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ^ Tacitus, Germania(online text Archived 18 April 2003 at the Wayback Machine): Ergo iam dextro Suebici maris litore Aestiorum gentes adluuntur, quibus ritus habitusque Sueborum, lingua Britannicae propior. – "Upon the right of the Suevian Sea the Æstyan nations reside, who use the same customs and attire with the Suevians; their language more resembles that of Britain." (English text online Archived 1 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Benario, Herbert W. (1 July 1999). Tacitus: Germania. Liverpool University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-80034-609-3. Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ Ptolemy, Geography III, chapter 5: "Sarmatia in Europe is bounded on the north by the Sarmatian ocean at the Venedic gulf" (online text Archived 3 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ (in Swedish) Balteus Archived 27 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine in Nordisk familjebok.

- ^ "Indo-European etymology : Query result". 25 February 2007. Archived from the original on 25 February 2007.

- ^ Schmitt 1989, pp. 310–313.

- ^ Forbes, Nevill (1910). The Position of the Slavonic Languages at the present day. Oxford University Press. p. 7.

- ^ Dini, Pietro Umberto (1997). Le lingue baltiche (in Italian). Florence: La Nuova Italia. ISBN 978-88-221-2803-4.

- ^ Cfr. Hartmann Schedel's 1493 (map), where the Baltic Sea is called Mare Germanicum, whereas the Northern Sea is called Oceanus Germanicus.

- ^ The Old English Orosius

- ^ Portham, 1880, p61

- ^ "Livones.net - Burājot lībiešu jūrā: debespušu nosaukumi lībiešu valodā". www.livones.net. Archived from the original on 20 July 2023. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ "A JOURNEY ALONG THE LIVONIAN COAST / REIZ PIDS LĪVÕD RANDÕ" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 July 2023. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ "The History of Russian Amber, Part 1: The Beginning" Archived 15 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Leta.st

- ^ Wend – West Wend Archived 22 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Britannica. Retrieved on 23 June 2011.

- ^ Chemical Weapon Time Bomb Ticks in the Baltic Sea Archived 24 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine Deutsche Welle, 1 February 2008.

- ^ Activities 2006: Overview Archived 14 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine Baltic Sea Environment Proceedings No. 112. Helsinki Commission.

- ^ Ellis, M.G.M.W. (1986). "Sweden's Ghosts?". Proceedings. 112 (3). United States Naval Institute: 95–101.

- ^ Kirby, Paul (4 April 2023). "Nato's border with Russia doubles as Finland joins". BBC News. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ^ "Does Sweden joining make the Baltic Sea a 'NATO lake'?". RFI. 26 February 2024. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ "No longer neutral waters: What Baltic Sea strategy for Sweden after NATO enlargement?". France 24. 28 March 2024. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ Milne, Richard; Seddon, Max (7 March 2024). "Sweden joins 'Nato lake' on Moscow's doorstep". Financial Times. Retrieved 7 March 2024.

- ^ Kayali, Laura (13 July 2023). "Sorry Russia, the Baltic Sea is NATO's lake now". POLITICO. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ Sztobryn, Marzenna; Stigge, Hans-Joachim; Wielbińska, Danuta; Weidig, Bärbel; Stanisławczyk, Ida; Kańska, Alicja; Krzysztofik, Katarzyna; Kowalska, Beata; Letkiewicz, Beata; Mykita, Monika (2005). "Sturmfluten in der südlichen Ostsee (Westlicher und mittlerer Teil)" [Storm floods in the Southern Baltic (western and central part)] (PDF). Berichte des Bundesamtes für Seeschifffahrt und Hydrographie (in German) (39): 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ^ "Sturmfluten an der Ostseeküste – eine vergessene Gefahr?" [Storm floods along the Baltic Sea coastline – a forgotten threat?]. Informations-, Lern-, und Lehrmodule zu den Themen Küste, Meer und Integriertes Küstenzonenmanagement. EUCC Die Küsten Union Deutschland e. V. Archived from the original on 24 July 2014. Retrieved 2 July 2012. Citing Weiss, D. "Schutz der Ostseeküste von Mecklenburg-Vorpommern". In Kramer, J.; Rohde, H. (eds.). Historischer Küstenschutz: Deichbau, Inselschutz und Binnenentwässerung an Nord- und Ostsee [Historical coastal protection: construction of dikes, insular protection and inland drainage at North Sea and Baltic Sea] (in German). Stuttgart: Wittwer. pp. 536–567.

- ^ Tiesel, Reiner (October 2003). "Sturmfluten an der deutschen Ostseeküste" [Storm floods at the German Baltic Sea coasts]. Informations-, Lern-, und Lehrmodule zu den Themen Küste, Meer und Integriertes Küstenzonenmanagement (in German). EUCC Die Küsten Union Deutschland e. V. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ^ "EuroOcean". Archived from the original on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ^ "Geography of the Baltic Sea Area". Archived from the original on 21 April 2006. Retrieved 27 August 2005. at envir.ee. (archived) (21 April 2006). Retrieved on 23 June 2011.

- ^ "p. 7" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ^ "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ "Baltic Sea area clickable map". www.baltic.vtt.fi. Archived from the original on 23 October 2007. Retrieved 11 April 2008.

- ^ a b c d e "Our Baltic Sea". HELCOM. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ^ Helsingin Sanomat, 16 February 2011, p. A8.

- ^ Derham, William Physico-Theology: Or, A Demonstration of the Being and Attributes of God from His Works of Creation (London, 1713).

- ^ Helsingin Sanomat, 10 February 2011, p. A4; 25 February 2011, p. A5; 11 June 2011, p. A12.

- ^ Sea Ice Survey Archived 25 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine Space Science and Engineering Center, University of Wisconsin.

- ^ "Nödåret 1867". Byar i Luleå. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011.

- ^ "Isvintrene i 40'erne". TV 2. 19 January 2008. Archived from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ "1771 – Nationalmuseet". Archived from the original on 16 April 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- ^ "Is i de danske farvande i 1700-tallet". Nationalmuseet. Archived from the original on 18 February 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ a b Alhonen, p. 88

- ^ Mohrholz, Volker (2018). "Major Baltic Inflow Statistics – Revised". Frontiers in Marine Science. 5. doi:10.3389/fmars.2018.00384. ISSN 2296-7745.

- ^ Lehmann, Andreas; Myrberg, Kai; Post, Piia; Chubarenko, Irina; Dailidiene, Inga; Hinrichsen, Hans-Harald; Hüssy, Karin; Liblik, Taavi; Meier, H. E. Markus; Lips, Urmas; Bukanova, Tatiana (16 February 2022). "Salinity dynamics of the Baltic Sea". Earth System Dynamics. 13 (1): 373–392. Bibcode:2022ESD....13..373L. doi:10.5194/esd-13-373-2022. ISSN 2190-4979. Archived from the original on 21 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ Medvedev, I. P.; Rabinovich, A. B.; Kulikov, E. A. (September 2013). "Tidal oscillations in the Baltic Sea". Oceanology. 53 (5): 526–538. Bibcode:2013Ocgy...53..526M. doi:10.1134/S0001437013050123. ISSN 0001-4370. S2CID 129778127. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ^ Rutgersson, Anna; Kjellström, Erik; Haapala, Jari; Stendel, Martin; Danilovich, Irina; Drews, Martin; Jylhä, Kirsti; Kujala, Pentti; Guo Larsén, Xiaoli; Halsnæs, Kirsten; Lehtonen, Ilari (6 April 2021). "Natural Hazards and Extreme Events in the Baltic Sea region". Earth System Dynamics Discussions. 13 (1): 251–301. doi:10.5194/esd-2021-13. ISSN 2190-4979. S2CID 233556209. Archived from the original on 29 September 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ a b Snoeijs-Leijonmalm P.; E.Andrén (2017). "Why is the Baltic Sea so special to live in?". In P. Snoeijs-Leijonmalm; H. Schubert; T. Radziejewska (eds.). Biological Oceanography of the Baltic Sea. Springer, Dordrecht. pp. 23–84. ISBN 978-94-007-0667-5.

- ^ a b c Viktorsson, L. (16 April 2018). "Hydrogeography and oxygen in the deep basins". HELCOM. Archived from the original on 27 July 2018. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ^ "The Baltic Sea: Its Past, Present and Future" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2007. (352 KB), Jan Thulin and Andris Andrushaitis, Religion, Science and the Environment Symposium V on the Baltic Sea (2003).

- ^ a b Muus, B.; J.G. Nielsen; P. Dahlstrom; B. Nystrom (1999). Sea Fish. Scandinavian Fishing Year Book. ISBN 978-8790787004.

- ^ Sweitzer, J (May 2019). "Land Use and Population Density in the Baltic Sea Drainage Basin: A GIS Database". Ambio. 25: 20. Archived from the original on 30 May 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2019 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Statistische Kurzinformation Archived 11 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine (in German). Landeshauptstadt Kiel. Amt für Kommunikation, Standortmarketing und Wirtschaftsfragen Abteilung Statistik. Retrieved on 11 October 2012.

- ^ Rosentau, A.; Klemann, V.; Bennike, O.; Steffen, H.; Wehr, J.; Latinović, M.; Bagge, M.; Ojala, A.; Berglund, M.; Becher, G.P.; Schoning, K. (2021). "A Holocene relative sea-level database for the Baltic Sea". Quaternary Science Reviews. 266. 107071. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2021.107071.

- ^ Mikkelson, David (9 January 2015). "UFO at the Bottom of the Baltic Sea? Rumor: Photograph shows a UFO discovered at the bottom of the Baltic Sea". Urban Legends Reference Pages© 1995-2017 by Snopes.com. Snopes.com. Archived from the original on 30 May 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ Kershner, Kate (7 April 2015). "What is the Baltic Sea anomaly?". How Stuff Works. HowStuffWorks, a division of InfoSpace Holdings LLC. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ Wolchover, Natalie (30 August 2012). "Mysterious' Baltic Sea Object Is a Glacial Deposit". Live Science. Live Science, Purch. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ Main, Douglas (2 January 2012). "Underwater UFO? Get Real, Experts Say". Popular Mechanics. Archived from the original on 28 December 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ Interview of Finnish planetary geomorphologist Jarmo Korteniemi (at 1:10:45) on Mars Moon Space Tv (30 January 2017), Baltic Sea Anomaly. The Unsolved Mystery. Part 1-2, archived from the original on 23 November 2021, retrieved 14 March 2018

- ^ Nissling, L.; A. Westin (1997). "Salinity requirements for successful spawning of Baltic and Belt Sea cod and the potential for cod stock interactions in the Baltic Sea". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 152 (1/3): 261–271. Bibcode:1997MEPS..152..261N. doi:10.3354/meps152261.

- ^ a b Momigliano, M.; G.P.J. Denys; H. Jokinen; J. Merilä (2018). "Platichthys solemdali sp. nov. (Actinopterygii, Pleuronectiformes): A New Flounder Species From the Baltic Sea". Front. Mar. Sci. 5 (225). doi:10.3389/fmars.2018.00225.

- ^ Rydén, Lars; Migula, Pawel; Andersson, Magnus (11 January 2024). Environmental Science : Understanding, Protecting and Managing the Environment in the Baltic Sea Region. Baltic University Press. ISBN 978-91-970017-0-0. Archived from the original on 15 October 2023. Retrieved 24 September 2023.

- ^ Lockwood, A. P. M.; Sheader, M.; Williams, J. A. (1998). "Life in Estuaries, Salt Marshes, Lagoons and Coastal Waters". In Summerhayes, C. P.; Thorpe, S. A. (eds.). Oceanography: An Illustrated Guide (2nd ed.). London: Manson Publishing. p. 246. ISBN 978-1-874545-37-8.

- ^ Pereyra, R.T.; L. Bergström; L. Kautsky; K. Johannesson (2009). "Rapid speciation in a newly opened postglacial marine environment, the Baltic Sea". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 9 (70): 70. Bibcode:2009BMCEE...9...70P. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-9-70. PMC 2674422. PMID 19335884.

- ^ Red List Benthic Invertebrate Expert Group (2013) Parvicardium hauniense. HELCOM. Accessed 27 July 2018.

- ^ "Parvicardium hauniense". National Museum Wales. 17 May 2016. Archived from the original on 27 July 2018. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ^ Minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) Archived 30 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine – MarLIN, The Marine Life Information Network

- ^ "Baltic dolphin sightings confirmed". Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- ^ About the beluga Archived 31 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine – Russian Geographical Society

- ^ Reeves, R.; Pitman, R.L.; Ford, J.K.B. (2017). "Orcinus orca". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T15421A50368125. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T15421A50368125.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "Rare Sowerby's beaked whale spotted in the Baltic Sea". Archived from the original on 19 November 2015. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- ^ "Wieder Finnwal in der Ostsee". Archived from the original on 15 April 2016.

- ^ KG, Ostsee-Zeitung GmbH & Co. "Finnwal in der Ostsee gesichtet". www.ostsee-zeitung.de. Archived from the original on 30 October 2016. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- ^ Allgemeine, Augsburger (17 July 2015). "Angler filmt Wal in Ostsee-Bucht". Archived from the original on 30 October 2016. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- ^ Jansson N.. 2007. "Vi såg valen i viken" Archived 7 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Aftonbladet. Retrieved on 7 September 2017.

- ^ "Whales seen again in the waters of the Baltic Sea". Science in Poland. Archived from the original on 4 July 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Jones L.M..Swartz L.S.. Leatherwood S.. The Gray Whale: Eschrichtius Robustus Archived 27 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine. "Eastern Atlantic Specimens". pp. 41–44. Academic Press. Retrieved on 5 September 2017

- ^ Global Biodiversity Information Facility. Occurrence Detail 1322462463 Archived 6 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 21 September 2017

- ^ Berry, George. "North Atlantic right whale". Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ "Regional Species Extinctions – Examples of regional species extinctions over the last 1000 years and more" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2011.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2019. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Satellite spies vast algal bloom in Baltic Sea". BBC News. 23 July 2010. Archived from the original on 26 July 2010. Retrieved 27 July 2010.

- ^ "Oxygenation at a Depth of 120 Meters Could Save the Baltic Sea, Researchers Demonstrate". Science Daily. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ "Ticking time bombs on the bottom of the North and Baltic Sea". DW.COM. 23 August 2017. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ Korkman, Anna. "Warming Baltic Sea: a red flag for global oceans". Phys.org. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d Meier, H.M.; Kniebusch, M.; Dieterich, C.; Gröger, M.; Zorita, E.; Elmgren, R.V; Myrberg, K.; Ahola, M.P.; Bartosova, A.; Bonsdorff, E.; Börgel, F. (15 March 2022). "Climate change in the Baltic Sea region: a summary". Earth System Dynamics. 13 (1): 457–593. Bibcode:2022ESD....13..457M. doi:10.5194/esd-13-457-2022. hdl:11250/3043839.

- ^ Trakimavicius, Lukas. "A Sea of Change: Energy Security in the Baltic region". EurActiv. Archived from the original on 26 July 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ Helcom : Welcome Archived 6 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Helcom.fi. Retrieved on 23 June 2011.

Bibliography

- Alhonen, Pentti (1966). "Baltic Sea". In Fairbridge, Rhodes (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Oceanography. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company. pp. 87–91.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (1989). "BLACK SEA". Black Sea – Encyclopaedia Iranica. Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 3. pp. 310–313.

Further reading

- Norbert Götz. "Spatial Politics and Fuzzy Regionalism: The Case of the Baltic Sea Area." Baltic Worlds 9 (2016) 3: 54–67.

- Aarno Voipio (ed., 1981): "The Baltic Sea." Elsevier Oceanography Series, vol. 30, Elsevier Scientific Publishing, 418 p, ISBN 0-444-41884-9

- Ojaveer, H.; Jaanus, A.; MacKenzie, B. R.; Martin, G.; Olenin, S.; et al. (2010). "Status of Biodiversity in the Baltic Sea". PLoS ONE. 5 (9): e12467. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...512467O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012467. PMC 2931693. PMID 20824189.

- Peter, Bruce (2009). Baltic Ferries. Ramsey, Isle of Man: Ferry Publications. ISBN 9781906608057.

- The BACC II Author Team; et al. (2015). Second Assessment of Climate Change for the Baltic Sea Basin. Regional Climate Studies. Springer. Bibcode:2015sacc.book.....T. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-16006-1. ISBN 978-3-319-16006-1. S2CID 127011711.

Historical

- Bogucka, Maria. "The Role of Baltic Trade in European Development from the XVIth to the XVIIIth Centuries". Journal of European Economic History 9 (1980): 5–20.

- Davey, James. The Transformation of British Naval Strategy: Seapower and Supply in Northern Europe, 1808–1812 (Boydell, 2012).

- Dickson, Henry Newton (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). pp. 286–287.

- Fedorowicz, Jan K. England's Baltic Trade in the Early Seventeenth Century: A Study in Anglo-Polish Commercial Diplomacy (Cambridge UP, 2008).

- Frost, Robert I. The Northern Wars: War, State, and Society in Northeastern Europe, 1558–1721 (Longman, 2000).

- Grainger, John D. The British Navy in the Baltic (Boydell, 2014).

- Kent, Heinz S. K. War and Trade in Northern Seas: Anglo-Scandinavian Economic Relations in the Mid Eighteenth Century (Cambridge UP, 1973).

- Koningsbrugge, Hans van. "In War and Peace: The Dutch and the Baltic in Early Modern Times". Tijdschrift voor Skandinavistiek 16 (1995): 189–200.

- Lindblad, Jan Thomas. "Structural Change in the Dutch Trade in the Baltic in the Eighteenth Century". Scandinavian Economic History Review 33 (1985): 193–207.

- Lisk, Jill. The Struggle for Supremacy in the Baltic, 1600–1725 (U of London Press, 1967).

- Niktalab, Poopak (2024). Over the Alps: History of Children and Youth literature in Europe (Chapter 2 Baltic sails: the evolution of children's and youth literature in the Baltic countries) (in Persian) (1st ed.). Tehran, Iran: Faradid Publisher. pp. 85–124. ISBN 9786225740457.

- Roberts, Michael. The Early Vasas: A History of Sweden, 1523–1611 (Cambridge UP, 1968).

- Rystad, Göran, Klaus-R. Böhme, and Wilhelm M. Carlgren, eds. In Quest of Trade and Security: The Baltic in Power Politics, 1500–1990. Vol. 1, 1500–1890. Stockholm: Probus, 1994.

- Salmon, Patrick, and Tony Barrow, eds. Britain and the Baltic: Studies in Commercial, Political and Cultural Relations (Sunderland University Press, 2003).

- Stiles, Andrina. Sweden and the Baltic 1523–1721 (1992).

- Thomson, Erik. "Beyond the Military State: Sweden's Great Power Period in Recent Historiography". History Compass 9 (2011): 269–283. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2011.00761.x

- Tielhof, Milja van. The "Mother of All Trades": The Baltic Grain Trade in Amsterdam from the Late 16th to Early 19th Century. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2002.

- Warner, Richard. "British Merchants and Russian Men-of-War: The Rise of the Russian Baltic Fleet". In Peter the Great and the West: New Perspectives. Edited by Lindsey Hughes, 105–117. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001.

External links

- The Baltic Sea, Kattegat and Skagerrak – sea areas and draining basins, poster with integral information by the Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute

- Baltic Sea clickable map and details.

- Protect the Baltic Sea while it's still not too late.

- The Baltic Sea Portal – a site maintained by the"Finnish Institute of Marine Research". Archived from the original on 14 February 2008. Retrieved 15 July 2007. (FIMR) (in English, Finnish, Swedish and Estonian)

- www.balticnest.org

- Encyclopedia of Baltic History

- Old shipwrecks in the Baltic

- How the Baltic Sea was changing – Prehistory of the Baltic from the Polish Geological Institute

- Late Weichselian and Holocene shore displacement history of the Baltic Sea in Finland – more prehistory of the Baltic from the Department of Geography of the University of Helsinki

- Baltic Environmental Atlas: Interactive map of the Baltic Sea region

- Can a New Cleanup Plan Save the Sea? – spiegel.de

- List of all ferry lines in the Baltic Sea

- The Helsinki Commission (HELCOM) HELCOM is the governing body of the "Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Area"

- Baltice.org – information related to winter navigation in the Baltic Sea.

- Baltic Sea Wind – Marine weather forecasts

- Ostseeflug – A short film (55'), showing the coastline and the major German cities at the Baltic sea.

13 Annotations

Third Reading

San Diego Sarah • Link

The Baltic countries are Sweden, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Denmark, Germany, and Russia, and their ports were used by cities in the Hansiatic League which, by the 17th century, was almost irrelevant. Trade was thriving, but the merchants no longer needed a League.

The Hanseatic League ports mostly traded fish (herring and stock fish), lumber, hemp, flax, grain, honey, fur, tar, salt, iron, silver, amber, spices, wine, cloth, and leather. England particularly liked their masts.

London was considered an outlier Hansiatic port, but to trade with the Baltic in the 17th century meant dodging pirates and privateers. Therefore, the Navy provided armed escorts for fleets of merchantmen.

Lithuania’s union with Poland consisted of a loose alliance. In 1569, the union was refashioned by a joint parliament in Lublin into a Commonwealth of Two Peoples. While the state entity now had a common elected sovereign and a joint parliament, the legal and administrative structures of the two lands, as well as their armies, remained separate. This arrangement lasted 200 years.

The Polish-Lithuanian union brought a time of political glory, prosperity, and cultural development. Until the middle of the 17th century, the Commonwealth contained the threat from Moscow. During the Time of Troubles in Muscovy at the beginning of the 17th century, a Polish-Lithuanian force occupied Moscow. The Catholic Counter-Reformation that accompanied the union placed an indelible stamp on Lithuania. Vilnius emerged as a centre of Baroque culture. Its university, founded in 1579, is the oldest institution of higher learning in that part of the world.

The Confederation was unable to withstand the onslaughts of Tsar Ivan IV (the Terrible), who in 1558 claimed the region in order to gain a sea port. The region broke into 3 duchies — Courland, Livonia, and Estland — which lasted until 1917.

Estland, the northern part of modern Estonia, came under Swedish rule. Livonia, with its capital, Riga, became a part of Lithuania, while Courland became a hereditary duchy nominally under Lithuanian suzerainty.

In 1592 Sweden threatened the Baltic lands in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The bulk of Livonia, with Riga, was ceded to Sweden in 1629. The southeastern portion, Latgale, remained a part of Lithuania.

The Swedish period brought peace between Estonia and Latvia. The Swedish kings, used to a free peasantry, made the local nobles improve the serfs' conditions. Compulsory elementary education was introduced, the Bible was translated into indigenous languages, a secondary school was opened in Riga in 1631 and a university in Dorpat in 1632. But more Swedish efforts were largely thwarted by wars.