Wikipedia

This text was copied from Wikipedia on 12 November 2024 at 5:10AM.

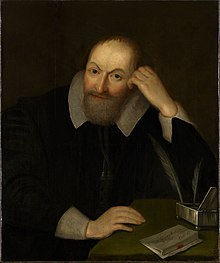

Henry Wotton | |

|---|---|

Sir Henry Wotton, Government Art Collection, London. | |

| Chief Secretary for Ireland | |

| In office 1599–1599 | |

| Preceded by | Philip Williams |

| Succeeded by | Francis Mitchell |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 30 March 1568 England, Kingdom of England |

| Died | December 1639(1639-12-00) (aged 71) |

| Parent | Thomas Wotton |

| Alma mater | University of Oxford |

Sir Henry Wotton (/ˈwʊtən/; 30 March 1568 – December 1639) was an English author, diplomat[1] and politician who sat in the House of Commons in 1614 and 1625. When on a mission to Augsburg in 1604, he famously said "An ambassador is an honest gentleman sent to lie abroad for the good of his country".

Life

The son of Thomas Wotton (1521–1587) and his second wife, Elionora Finch, Henry was the youngest brother of Edward Wotton, and grandnephew of the diplomat Nicholas[2] and Margaret Wotton. Henry was born at Bocton Hall in the parish of Bocton or Boughton Malherbe, Kent. He was educated at Winchester College[3] and at New College, Oxford, where he matriculated on 5 June 1584,[4] alongside John Hoskins.[5] Two years later, he moved to Queen's College, graduating in 1588.[4]

At Oxford, he was the friend of Alberico Gentili, then professor of Civil Law, and of John Donne. During his residence at Queen's, he wrote a play, Tancredo,[6] which has not survived, but his chief interests appear to have been scientific. In qualifying for his M.A. degree he read three lectures De oculo, and to the end of his life, he continued to interest himself in physical experiments.[5]

His father, Thomas Wotton, died in 1587, leaving Henry only a hundred marks a year. About 1589 Wotton went abroad, with a view probably to preparation for a diplomatic career, and his travels appear to have lasted for about six years. At Altdorf he met Edward, Lord Zouch, to whom he later addressed a series of letters (1590–1593) which contain much political and other news, and provide a record of the journey. He travelled by way of Vienna and Venice to Rome, and in 1593 spent some time at Geneva in the house of Isaac Casaubon, to whom he contracted a considerable debt.[7]

He returned to England in 1594, and in the next year was admitted to the Middle Temple. While abroad he had from time to time provided Robert Devereux with information, and he now definitely entered his service as one of his agents or secretaries. It was his duty to supply intelligence of affairs in Transylvania, Poland, Italy and Germany.[8] He served as Essex's secretary in Ireland from 15 April 1599 until 4 September 1599.[9]

Wotton was not directly involved in the Essex Rebellion; this contrasts with his fellow-secretary, Henry Cuffe, who was hanged at Tyburn in 1601. However, he thought it prudent to leave England, and within sixteen hours of Essex's apprehension he was safe in France, whence he travelled to Venice and Rome.[8]

In 1602, he was living in Florence, and a plot to murder James VI of Scotland having come to the ears of the grand duke of Tuscany, Wotton was entrusted with letters to warn the king of the danger, and with Italian antidotes against poison. As "Ottavio Baldi" he travelled to Scotland by way of Norway. He was well received by James, and remained for three months at the Scottish court, retaining his Italian incognito. He then returned to Florence, but on receiving the news of James's accession hurried to England. James knighted him, and offered him the embassy at Madrid or Paris; but Wotton, knowing that both these offices involved ruinous expense, desired rather to represent James at Venice.[8]

He left London in 1604 accompanied by Sir Albertus Morton, his half-nephew, as secretary, and William Bedell, the author of an Irish translation of the Bible, as chaplain. Wotton spent most of the next twenty years, with two breaks (1612–16 and 1619–21), at Venice. He helped the Doge in his resistance to ecclesiastical aggression, and was closely associated with Paolo Sarpi, whose history of the Council of Trent was sent to King James as fast as it was written. Wotton had offended the scholar Caspar Schoppe, who had been a fellow student at Altdorf.[8]

In 1611, Schoppe wrote a scurrilous book against James entitled Ecclesiasticus, in which he fastened on Wotton a saying which he had incautiously written in friend, Christoff Fleckhammer's, album years before. It was the famous definition of an ambassador as an "honest man sent to lie abroad for the good of his country" (Legatus est vir bonus peregre missus ad mentiendum rei publicae causa). It should be noticed that the original Latin form of the epigram did not admit to the double meaning. This was adduced as an example of the morals of James and his servants, and brought Wotton into temporary disgrace. Wotton was at the time on leave in England, and made two formal defences of himself, one a personal attack on his accuser addressed to Mark Welser of Augsburg, and the other privately to the king.[8]

He obtained no diplomatic employment for some time, but seems to have finally won back the royal favour by his parliamentary support for James's claim to impose arbitrary taxes on merchandise.[8] In 1614 he was elected Member of Parliament for Appleby in the Addled Parliament.[4]

He was sent to the Hague and, in 1616, he returned to Venice. In 1620 he was sent on a special embassy to Ferdinand II at Vienna, to do what he could on behalf of James's daughter Elizabeth of Bohemia. Wotton's devotion to this princess, expressed in his exquisite verses beginning "You meaner beauties of the night," was sincere and unchanging. At his departure, the emperor presented him with a valuable jewel, which Wotton received with due respect, but before leaving the city he gave it to his hostess, because, he said, he would accept no gifts from the enemy of the Bohemian queen.[8]

After a third term of service in Venice he returned to London early in 1624 and in July he was installed as provost of Eton College.[8] This office did not resolve his financial problems, and he was on one occasion arrested for debt. In 1625 he was elected MP for Sandwich.

In 1627, he received a pension of £200, and in 1630 this was raised to £500 on the understanding that he should write a history of England. He did not neglect the duties of his provostship, and was happy in being able to entertain his friends lavishly. His most constant associates were Izaak Walton and John Hales. A bend in the Thames below the Playing Fields, known as "Black Potts," is still pointed out as the spot where Wotton and Walton fished in company. He died at the beginning of December 1639 and was buried in the chapel of Eton College.[8]

Works

Of 25 poems printed in Reliquiae Wottonianae 15 are Wotton's. Of those, two are well known, "O his Mistris, the Queen of Bohemia," and "The Character of a Happy Life". Another much-quoted work is his epitaph for Elizabeth Apsley, the widow of his nephew Sir Albertus Morton: "He first deceased, she for a little tried to live without him, liked it not, and died".

During his lifetime he published two works: The Elements of Architecture (1624), which is a free translation of de Architectura by Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, executed during his time in Venice; and a Latin prose address to the king on his return from Scotland (1633). Wotton shares authorship of the quote "Well building hath three conditions: firmness, commodity, and delight", with Vitruvius, from whose de Architectura Wotton translated the phrase; some have termed his Elements a paraphrase rather than a true translation, and the quote is often attributed to Vitruvius.

In 1651 appeared the Reliquiae Wottonianiae, with Izaak Walton's Life.[8]

References

- ^ Lee, Sidney (1900). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 63. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ Wotton, Henry, Reliquiae Wottonianae, (1672), unpaginated.

- ^ Walton, Izaak. "The Life of Sir Henry Wotton". Anglican History. Project Canterbury. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ a b c 'Alumni Oxonienses, 1500–1714: Woodall-Wyvill', Alumni Oxonienses 1500–1714 (1891), pp. 1674–1697. Retrieved 8 May 2012

- ^ a b Chisholm 1911, p. 836.

- ^ Teramura, Misha. "Tancredo". Lost Plays Database. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ Chisholm 1911, pp. 836–837.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Chisholm 1911, p. 837.

- ^ Titled Elizabethans: A Directory of Elizabethan Court, State, and Church edited by Arthur F. Kinney, Jane A. Lawson.

Sources

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Wotton, Sir Henry". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 836–837.

- Loomie, A. J. "Wotton, Sir Henry (1568–1639)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/30001. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Further reading

- Chaney, Edward: The Evolution of the Grand Tour: Anglo-Italian Cultural Relations since the Renaissance Routledge 2000

- Curzon, Gerald: "Wotton And His Worlds: Spying, science and Venetian Intrigues" 2004

- Smith, L.P.: Henry Wotton: Life and Letters 1907

- Villani, Stefano: "Wotton e l’Italia: Alcune note sulle dediche ad Henry Wotton di Fonti Toscani di Orazio Lombardelli (1598) e di Morte Innamorata di Fabio Glissenti (1608)", Bruniana & Campanelliana, 29, 2003, pp. 69-87

- A.W. Ward: Sir Henry Wotton, a Biographical Sketch 1898

- Wotton, Henry, Reliquiae Wottonianae, or, A collection of lives, letters, poems, London (1672)

External links

- Works by or about Henry Wotton at the Internet Archive

- Works by Henry Wotton at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Characters of Robert Devereux and George Villiers (1641)

- Hutchinson, John (1892). . Men of Kent and Kentishmen (Subscription ed.). Canterbury: Cross & Jackman. pp. 146–147.

0 Annotations