The area shown on the map is based approximately on the location of the Roman walls.

The City of London

Map

The overlays that highlight 17th century London features are approximate and derived from Wenceslaus Hollar’s maps:

- Built-up London – London before the Fire

- City of London wall and Great Fire damage – London after the Fire

Open location in Google Maps: 51.513389, -0.090723

Wikipedia

This text was copied from Wikipedia on 22 December 2024 at 6:10AM.

City of London | |

|---|---|

| Nicknames: the Square Mile, the City | |

| Motto(s): | |

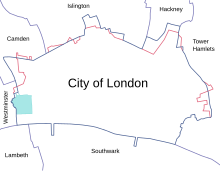

Location within Greater London | |

| Coordinates: 51°30′56″N 00°05′35″W / 51.51556°N 0.09306°W / 51.51556; -0.09306 | |

| Status | Sui generis; city and ceremonial county |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | England |

| Region | London |

| Roman settlement | c. 47 AD (Londinium) |

| Wessex resettlement | 886 AD (Lundenburg) |

| Wards | |

| Government | |

| • Body | City of London Corporation |

| • Lord Mayor | Alastair John Naisbitt King |

| • Town Clerk | Ian Thomas |

| • Admin HQ | Guildhall |

| • London Assembly | Unmesh Desai (Lab; City and East) |

| • UK Parliament | Rachel Blake (Lab; Cities of London and Westminster) |

| Area | |

• City | 1.12 sq mi (2.90 km2) |

| Highest elevation | 69 ft (21 m) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Population (2022) | |

• City | 10,847 |

| • Rank | 295th (of 296) |

| • Density | 9,700/sq mi (3,700/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC±00:00 (GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+01:00 (BST) |

| Postcodes | |

| Area code | 020 |

| Geocode |

|

| ISO 3166-2 | GB-LND |

| Police | City of London Police |

| Patron saint | St. Paul |

| Website | cityoflondon.gov.uk |

| |

The City of London, also known as the City, is a city, ceremonial county and local government district[note 1] that contains the ancient centre, and constitutes, along with Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London and one of the leading financial centres of the world.[2] It constituted most of London from its settlement by the Romans in the 1st century AD to the Middle Ages, but the modern area referred to as London has since grown far beyond the City of London boundary.[3][4] The City is now only a small part of the metropolis of Greater London, though it remains a notable part of central London. The City of London is not one of the London boroughs, a status reserved for the other 32 districts (including Greater London's only other city, the City of Westminster). It is also a separate ceremonial county, being an enclave surrounded by the ceremonial county of Greater London, and is the smallest ceremonial county in England.

The City of London is known colloquially as the Square Mile, as it is 1.12 sq mi (716.80 acres; 2.90 km2)[5] in area. Both the terms the City and the Square Mile are often used as metonyms for the UK's trading and financial services industries, which continue a notable history of being largely based in the City.[6] The name London is now ordinarily used for a far wider area than just the City. London most often denotes the sprawling London metropolis, or the 32 Greater London boroughs, in addition to the City of London itself.

The local authority for the City, namely the City of London Corporation, is unique in the UK and has some unusual responsibilities for a local council, such as being the police authority. It is also unusual in having responsibilities and ownerships beyond its boundaries, e.g. Hampstead Heath.[7] The corporation is headed by the Lord Mayor of the City of London (an office separate from, and much older than, the Mayor of London). The Lord Mayor, as of November 2023, is Michael Mainelli.[8] The City is made up of 25 wards, with administration at the historic Guildhall. Other historic sites include St Paul's Cathedral, Royal Exchange, Mansion House, Old Bailey, and Smithfield Market. Although not within the City, the adjacent Tower of London, built to dominate the City, is part of its old defensive perimeter. The City has responsibility for five bridges across the Thames in its capacity as trustee of the Bridge House Estates: Blackfriars Bridge, Millennium Bridge, Southwark Bridge, London Bridge and Tower Bridge.

The City is a major business and financial centre,[9] with both the Bank of England and the London Stock Exchange based in the City. Throughout the 19th century, the City was the world's primary business centre, and it continues to be a major meeting point for businesses.[10] London was ranked second (after New York) in the Global Financial Centres Index, published in 2022. The insurance industry is concentrated in the eastern side of the city, around Lloyd's building. Since about the 1980s, a secondary financial district has existed outside the city, at Canary Wharf, 2.5 miles (4 km) to the east. The legal profession has a major presence in the northern and western sides of the City, especially in the Temple and Chancery Lane areas where the Inns of Court are located, two of which (Inner Temple and Middle Temple) fall within the City of London boundary.

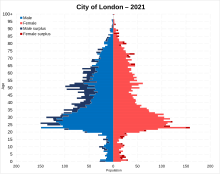

Primarily a business district, the City has a small resident population of 8,583 based on 2021 census figures,[11][12] but over 500,000 are employed there (as of 2019)[13] and some estimates put the number of workers in the City to be over 1 million. About three-quarters of the jobs in the City of London are in the financial, professional, and associated business services sectors.[14]

History

Origins

The Roman legions established a settlement known as "Londinium" on the current site of the City of London around AD 43. Its bridge over the River Thames turned the city into a road nexus and major port, serving as a major commercial centre in Roman Britain until its abandonment during the 5th century. Archaeologist Leslie Wallace notes that, because extensive archaeological excavation has not revealed any signs of a significant pre-Roman presence, "arguments for a purely Roman foundation of London are now common and uncontroversial."[15]

At its height, the Roman city had a population of approximately 45,000–60,000 inhabitants. Londinium was an ethnically diverse city, with inhabitants from across the Roman Empire, including natives of Britannia, continental Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa.[16] The Romans built the London Wall some time between AD 190 and 225. The boundaries of the Roman city were similar to those of the City of London today, though the City extends further west than Londinium's Ludgate, and the Thames was undredged and thus wider than it is today, with Londinium's shoreline slightly north of the city's present shoreline. The Romans built a bridge across the river, as early as AD 50, near to today's London Bridge.

Decline

By the time the London Wall was constructed, the city's fortunes were in decline, and it faced problems of plague and fire. The Roman Empire entered a long period of instability and decline, including the Carausian Revolt in Britain. In the 3rd and 4th centuries, the city was under attack from Picts, Scots, and Saxon raiders. The decline continued, both for Londinium and the Empire, and in AD 410 the Romans withdrew entirely from Britain. Many of the Roman public buildings in Londinium by this time had fallen into decay and disuse, and gradually after the formal withdrawal the city became almost (if not, at times, entirely) uninhabited. The centre of trade and population moved away from the walled Londinium to Lundenwic ("London market"), a settlement to the west, roughly in the modern-day Strand/Aldwych/Covent Garden area.

Anglo-Saxon restoration

During the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy, the London area came in turn under the Kingdoms of Essex, Mercia, and later Wessex, though from the mid 8th century it was frequently under threat from raids by different groups including the Vikings.

Bede records that in AD 604 St Augustine consecrated Mellitus as the first bishop to the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Saxons and their king, Sæberht. Sæberht's uncle and overlord, Æthelberht, king of Kent, built a church dedicated to St Paul in London, as the seat of the new bishop.[17] It is assumed, although unproven, that this first Anglo-Saxon cathedral stood on the same site as the later medieval and the present cathedrals.

Alfred the Great, King of Wessex occupied and began the resettlement of the old Roman walled area, in 886, and appointed his son-in-law Earl Æthelred of Mercia over it as part of their reconquest of the Viking occupied parts of England. The refortified Anglo-Saxon settlement was known as Lundenburh ("London Fort", a borough). The historian Asser said that "Alfred, king of the Anglo-Saxons, restored the city of London splendidly ... and made it habitable once more."[18] Alfred's "restoration" entailed reoccupying and refurbishing the nearly deserted Roman walled city, building quays along the Thames, and laying a new city street plan.[19]

Alfred's taking of London and the rebuilding of the old Roman city was a turning point in history, not only as the permanent establishment of the City of London, but also as part of a unifying moment in early England, with Wessex becoming the dominant English kingdom and the repelling (to some degree) of the Viking occupation and raids. While London, and indeed England, were afterwards subjected to further periods of Viking and Danish raids and occupation, the establishment of the City of London and the Kingdom of England prevailed.[20]

In the 10th century, Athelstan permitted eight mints to be established, compared with six in his capital, Winchester, indicating the wealth of the city. London Bridge, which had fallen into ruin following the Roman evacuation and abandonment of Londinium, was rebuilt by the Saxons, but was periodically destroyed by Viking raids and storms.

As the focus of trade and population was moved back to within the old Roman walls, the older Saxon settlement of Lundenwic was largely abandoned and gained the name of Ealdwic (the "old settlement"). The name survives today as Aldwych (the "old market-place"), a name of a street and an area of the City of Westminster between Westminster and the City of London.

Medieval era

Following the Battle of Hastings, William the Conqueror marched on London, reaching as far as Southwark, but failed to get across London Bridge or defeat the Londoners. He eventually crossed the River Thames at Wallingford, pillaging the land as he went. Rather than continuing the war, Edgar the Ætheling, Edwin of Mercia and Morcar of Northumbria surrendered at Berkhamsted. William granted the citizens of London a charter in 1075; the city was one of a few examples of the English retaining some authority. The city was not covered by the Domesday Book.

William built three castles around the city, to keep Londoners subdued:

- Tower of London, which is still a major establishment.

- Baynard's Castle, which no longer exists but gave its name to a city ward.

- Montfichet's Tower or Castle on Ludgate Hill, which was dismantled and sold off in the 13th century.

Around 1132 the City was given the right to appoint its own sheriffs rather than having sheriffs appointed by the monarch. London's chosen sheriffs also served as the sheriffs for the county of Middlesex. This meant that the City and Middlesex were regarded as one administratively for addressing crime and keeping the peace (not that the county was a dependency of the city). London's sheriffs continued to serve Middlesex until the county was given its own sheriffs again following the Local Government Act 1888.[21][22] By 1141 the whole body of the citizenry was considered to constitute a single community. This 'commune' was the origin of the City of London Corporation and the citizens gained the right to appoint, with the king's consent, a mayor in 1189—and to directly elect the mayor from 1215.

From medieval times, the city has been composed of 25 ancient wards, each headed by an alderman, who chairs Wardmotes, which still take place at least annually. A Folkmoot, for the whole of the City held at the outdoor cross of St Paul's Cathedral, was formerly also held. Many of the medieval offices and traditions continue to the present day, demonstrating the unique nature of the City and its Corporation.

In 1381, the Peasants' Revolt affected London. The rebels took the City and the Tower of London, but the rebellion ended after its leader, Wat Tyler, was killed during a confrontation that included Lord Mayor William Walworth. In 1450, rebel forces again occupied the City during Jack Cade's Rebellion before being ousted by London citizens following a bloody battle on London Bridge. In 1550, the area south of London Bridge in Southwark came under the control of the City with the establishment of the ward of Bridge Without.

The city was burnt severely on a number of occasions, the worst being in 1123 and in the Great Fire of London in 1666. Both of these fires were referred to as the Great Fire. After the fire of 1666, a number of plans were drawn up to remodel the city and its street pattern into a renaissance-style city with planned urban blocks, squares and boulevards. These plans were almost entirely not taken up, and the medieval street pattern re-emerged almost intact.

Early modern period

In the 1630s the Crown sought to have the Corporation of the City of London extend its jurisdiction to surrounding areas. In what is sometimes called the "great refusal", the Corporation said no to the King, which in part accounts for its unique government structure to the present.[23]

By the late 16th century, London increasingly became a major centre for banking, international trade and commerce. The Royal Exchange was founded in 1565 by Sir Thomas Gresham as a centre of commerce for London's merchants, and gained Royal patronage in 1571. Although no longer used for its original purpose, its location at the corner of Cornhill and Threadneedle Street continues to be the geographical centre of the city's core of banking and financial services, with the Bank of England moving to its present site in 1734, opposite the Royal Exchange. Immediately to the south of Cornhill, Lombard Street was the location from 1691 of Lloyd's Coffee House, which became the world-leading insurance market. London's insurance sector continues to be based in the area, particularly in Lime Street.

In 1708, Christopher Wren's masterpiece, St Paul's Cathedral, was completed on his birthday. The first service had been held on 2 December 1697, more than 10 years earlier. It replaced the original St Paul's, which had been completely destroyed in the Great Fire of London, and is considered to be one of the finest cathedrals in Britain and a fine example of Baroque architecture.

Growth of London

The 18th century was a period of rapid growth for London, reflecting an increasing national population, the early stirrings of the Industrial Revolution, and London's role at the centre of the evolving British Empire. The urban area expanded beyond the borders of the City of London, most notably during this period towards the West End and Westminster.

Expansion continued and became more rapid by the beginning of the 19th century, with London growing in all directions. To the East the Port of London grew rapidly during the century, with the construction of many docks, needed as the Thames at the City could not cope with the volume of trade. The arrival of the railways and the Tube meant that London could expand over a much greater area. By the mid-19th century, with London still rapidly expanding in population and area, the City had already become only a small part of the wider metropolis.

19th and 20th centuries

An attempt was made in 1894 with the Royal Commission on the Amalgamation of the City and County of London to end the distinction between the city and the surrounding County of London, but a change of government at Westminster meant the option was not taken up. The city as a distinct polity survived despite its position within the London conurbation and numerous local government reforms. Supporting this status, the city was a special parliamentary borough that elected four members to the unreformed House of Commons, who were retained after the Reform Act 1832; reduced to two under the Redistribution of Seats Act 1885; and ceased to be a separate constituency under the Representation of the People Act 1948. Since then the city is a minority (in terms of population and area) of the Cities of London and Westminster.

The city's population fell rapidly in the 19th century and through most of the 20th century, as people moved outwards in all directions to London's vast suburbs, and many residential buildings were demolished to make way for office blocks. Like many areas of London and other British cities, the City fell victim to large scale and highly destructive aerial bombing during World War II, especially in the Blitz. Whilst St Paul's Cathedral survived the onslaught, large swathes of the area did not and the particularly heavy raids of late December 1940 led to a firestorm called the Second Great Fire of London.

There was a major rebuilding programme in the decades following the war, in some parts (such as at the Barbican) dramatically altering the urban landscape. But the destruction of the older historic fabric allowed the construction of modern and larger-scale developments, whereas in those parts not so badly affected by bomb damage the City retains its older character of smaller buildings. The street pattern, which is still largely medieval, was altered slightly in places, although there is a more recent trend of reversing some of the post-war modernist changes made, such as at Paternoster Square.

The City suffered terrorist attacks including the 1993 Bishopsgate bombing (IRA) and the 7 July 2005 London bombings (Islamist). In response to the 1993 bombing, a system of road barriers, checkpoints and surveillance cameras referred to as the "ring of steel" has been maintained to control entry points to the city.

The 1970s saw the construction of tall office buildings including the 600-foot (183 m), 47-storey NatWest Tower, the first skyscraper in the UK. By the 2010s, office space development had intensified in the City, especially in the central, northern and eastern parts, with skyscrapers including 30 St. Mary Axe ("the Gherkin"'), Leadenhall Building ("the Cheesegrater"), 20 Fenchurch Street ("the Walkie-Talkie"), the Broadgate Tower, the Heron Tower and 22 Bishopsgate.

The main residential section of the City today is the Barbican Estate, constructed between 1965 and 1976. The Museum of London was based there until March 2023 (due to reopen in West Smithfield in 2026),[24] whilst a number of other services provided by the corporation are still maintained on the Barbican Estate.

Governance

The city has a unique political status, a legacy of its uninterrupted integrity as a corporate city since the Anglo-Saxon period and its singular relationship with the Crown. Historically its system of government was not unusual, but it was not reformed by the Municipal Corporations Act 1835 and little changed by later reforms, so that it is the only local government in the UK where elections are not run on the basis of one vote for every adult citizen.

It is administered by the City of London Corporation, headed by the Lord Mayor of London (not to be confused with the separate Mayor of London, an office created only in the year 2000), which is responsible for a number of functions and has interests in land beyond the city's boundaries. Unlike other English local authorities, the corporation has two council bodies: the (now largely ceremonial) Court of Aldermen and the Court of Common Council. The Court of Aldermen represents the wards, with each ward (irrespective of size) returning one alderman. The chief executive of the Corporation holds the ancient office of Town Clerk of London.

The city is a ceremonial county which has a Commission of Lieutenancy headed by the Lord Mayor instead of a Lord-Lieutenant and has two Sheriffs instead of a High Sheriff (see list of Sheriffs of London), quasi-judicial offices appointed by the livery companies, an ancient political system based on the representation and protection of trades (guilds). Senior members of the livery companies are known as liverymen and form the Common Hall, which chooses the lord mayor, the sheriffs and certain other officers.

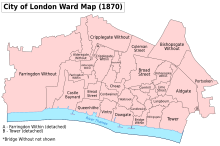

Wards

The city is made up of 25 wards. They are survivors of the medieval government system that allowed a very local area to exist as a self-governing unit within the wider city.[25] They can be described as electoral/political divisions; ceremonial, geographic and administrative entities; sub-divisions of the city. Each ward has an Alderman, who until the mid-1960s[26] held office for life but since put themselves up for re-election at least every 6 years, and are the only directly elected Aldermen in the United Kingdom. Wards continue to have a Beadle, an ancient position which is now largely ceremonial whose main remaining function is the running of an annual Wardmote of electors, representatives and officials.[27] At the Wardmote the ward's Alderman appoints at least one Deputy for the year ahead, and Wardmotes are also held during elections. Each ward also has a Ward Club, which is similar to a residents' association.[28]

The wards are ancient and their number has changed three times since time immemorial:

- in 1394 Farringdon was divided into Farringdon Within and Farringdon Without

- in 1550 the ward of Bridge Without, south of the river, was created, the ward of Bridge becoming Bridge Within;[29]

- in 1978 these Bridge wards were merged as Bridge ward.[30]

Following boundary changes in 1994, and later reform of the business vote in the city, there was a major boundary and electoral representation revision of the wards in 2003, and they were reviewed again in 2010 for change in 2013, though not to such a dramatic extent. The review was conducted by senior officers of the corporation and senior judges of the Old Bailey;[31] the wards are reviewed by this process to avoid malapportionment. The procedure of review is unique in the United Kingdom as it is not conducted by the Electoral Commission or a local government boundary commission every 8 to 12 years, which is the case for all other wards in Great Britain. Particular churches, livery company halls and other historic buildings and structures are associated with a ward, such as St Paul's Cathedral with Castle Baynard, and London Bridge with Bridge; boundary changes in 2003 removed some of these historic connections.

Each ward elects an alderman to the Court of Aldermen, and commoners (the City equivalent of a councillor) to the Court of Common Council of the corporation. Only electors who are Freemen of the City of London are eligible to stand. The number of commoners a ward sends to the Common Council varies from two to ten, depending on the number of electors in each ward. Since the 2003 review it has been agreed that the four more residential wards: Portsoken, Queenhithe, Aldersgate and Cripplegate together elect 20 of the 100 commoners, whereas the business-dominated remainder elect the remaining 80 commoners. 2003 and 2013 boundary changes have increased the residential emphasis of the mentioned four wards.

Census data provides eight nominal rather than 25 real wards, all of varying size and population. Being subject to renaming and definition at any time, these census 'wards' are notable in that four of the eight wards accounted for 67% of the 'square mile' and held 86% of the population, and these were in fact similar to and named after four City of London wards:

| Census ward | % of the City of London |

Residents | % of built-upon land | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial | Residential | |||

| Cripplegate (east half of Barbican neighbourhood) | 10.0% | 2,782 | 79% | 21% |

| Aldersgate (west half of Barbican neighbourhood) | 4.5% | 1,465 | 81% | 19% |

| Farringdon Without (and much of Castle Baynard) | 22.1% | 1,099 | 90% | 10% |

| Portsoken (contains Aldgate Underground station) | 6.6% | 985 | 86% | 14% |

Elections

The city has a unique electoral system. Most of its voters are representatives of businesses and other bodies that occupy premises in the city. Its ancient wards have very unequal numbers of voters. In elections, both the businesses based in the city and the residents of the City vote.

The City of London Corporation was not reformed by the Municipal Corporations Act 1835, because it had a more extensive electoral franchise than any other borough or city; in fact, it widened this further with its own equivalent legislation allowing one to become a freeman without being a liveryman. In 1801, the city had a population of about 130,000, but increasing development of the city as a central business district led to this falling to below 5,000 after the Second World War. It has risen slightly to around 9,000 since, largely due to the development of the Barbican Estate. In 2009, the business vote was about 24,000, greatly exceeding residential voters.[33] As the City of London Corporation has not been affected by other municipal legislation over the period of time since then, its electoral practice has become increasingly anomalous. Uniquely for city or borough elections, its elections remain independent-dominated.

The business or "non-residential vote" was abolished in other UK local council elections by the Representation of the People Act 1969, but was preserved in the City of London. The principal reason given by successive UK governments for retaining this mechanism for giving businesses representation, is that the city is "primarily a place for doing business".[34] About 330,000 non-residents constitute the day-time population and use most of its services, far outnumbering residents, who number around 7,000 (2011). By contrast, opponents of the retention of the business vote argue that it is a cause of institutional inertia.[35]

The City of London (Ward Elections) Act 2002, a private Act of Parliament,[36] reformed the voting system and greatly increased the business franchise, allowing many more businesses to be represented. Under the new system, the number of non-resident voters has doubled from 16,000 to 32,000. Previously disenfranchised firms (and other organisations) are entitled to nominate voters, in addition to those already represented, and all such bodies are now required to choose their voters in a representative fashion. Bodies employing fewer than 10 people may appoint 1 voter; those employing 10 to 50 people 1 voter for every 5 employees; those employing more than 50 people 10 voters and 1 additional voter for each 50 employees beyond the first 50. The Act also changed other aspects of an earlier act relating to elections in the city, from 1957.

The Temple

Inner Temple and Middle Temple (which neighbour each other) in the western ward of Farringdon Without are within the boundaries and liberties of the City, but can be thought of as independent enclaves. They are two of the few remaining liberties, an old name for a geographic division with special rights. They are extra-parochial areas,[37] historically not governed by the City of London Corporation[38] (and are today regarded as local authorities for most purposes[39]) and equally outside the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the Bishop of London.

Other functions

Within the city, the Corporation owns and runs both Smithfield Market and Leadenhall Market. It owns land beyond its boundaries, including open spaces (parks, forests and commons) in and around Greater London, including most of Epping Forest and Hampstead Heath. The Corporation owns Old Spitalfields Market and Billingsgate Fish Market, in the neighbouring London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It owns and helps fund the Old Bailey, the Central Criminal Court for England and Wales, as a gift to the nation, having begun as the City and Middlesex Sessions. The Honourable The Irish Society, a body closely linked with the corporation, also owns many public spaces in Northern Ireland.

The city has its own independent police force, the City of London Police—the Common Council (the main body of the corporation) is the police authority.[40] The corporation also run the Hampstead Heath Constabulary, Epping Forest Keepers and the City of London market constabularies (whose members are no longer attested as constables but retain the historic title). The majority of Greater London is policed by the Metropolitan Police Service, based at New Scotland Yard.

The city has one hospital, St Bartholomew's Hospital, also known as 'Barts'. Founded in 1123, it is located at Smithfield, and is undergoing a long-awaited regeneration after doubts as to its continuing use during the 1990s.

The city is the third largest UK patron of the arts. It oversees the Barbican Centre and subsidises several important performing arts companies.

The London Port Health Authority, which is the responsibility of the corporation, is responsible for all port health functions on the tidal part of the Thames, including the Port of London and related seaports, and London City Airport.[41] The Corporation oversees the Bridge House Estates, which maintains Blackfriars Bridge, Millennium Bridge, Southwark Bridge, London Bridge and Tower Bridge. The City's flag flies over Tower Bridge, although neither footing is in the city.[42]

The boundary of the City

The size of the city was constrained by a defensive perimeter wall, known as London Wall, which was built by the Romans in the late 2nd century to protect their strategic port city. However the boundaries of the City of London no longer coincide with the old city wall, as the City expanded its jurisdiction slightly over time. During the medieval era, the city's jurisdiction expanded westwards, crossing the historic western border of the original settlement—the River Fleet—along Fleet Street to Temple Bar. The city also took in the other "City bars" which were situated just beyond the old walled area, such as at Holborn, Aldersgate, West Smithfield, Bishopsgate and Aldgate. These were the important entrances to the city and their control was vital in maintaining the city's special privileges over certain trades.

Most of the wall has disappeared, but several sections remain visible. A section near the Museum of London was revealed after the devastation of an air raid on 29 December 1940 at the height of the Blitz. Other visible sections are at St Alphage, and there are two sections near the Tower of London. The River Fleet was canalised after the Great Fire of 1666 and then in stages was bricked up and has been since the 18th century one of London's "lost rivers or streams", today underground as a storm drain.

The boundary of the city was unchanged until minor boundary changes on 1 April 1994, when it expanded slightly to the west, north and east, taking small parcels of land from the London Boroughs of Westminster, Camden, Islington, Hackney and Tower Hamlets. The main purpose of these changes was to tidy up the boundary where it had been rendered obsolete by changes in the urban landscape. In this process the city also lost small parcels of land, though there was an overall net gain (the City grew from 1.05 to 1.12 square miles). Most notably, the changes placed the (then recently developed) Broadgate estate entirely in the city.[43]

Southwark, to the south of the city on the other side of the Thames, was within the City between 1550 and 1899 as the Ward of Bridge Without, a situation connected with the Guildable Manor. The city's administrative responsibility there had in practice disappeared by the mid-Victorian period as various aspects of metropolitan government were extended into the neighbouring areas. Today it is part of the London Borough of Southwark. The Tower of London has always been outside the city and comes under the London Borough of Tower Hamlets.

Arms, motto and flag

The Corporation of the City of London has a full achievement of armorial bearings consisting of a shield on which the arms are displayed, a crest displayed on a helm above the shield, supporters on either side and a motto displayed on a scroll beneath the arms.[44][45][46]

The coat of arms is "anciently recorded" at the College of Arms. The arms consist of a silver shield bearing a red cross with a red upright sword in the first quarter. They combine the emblems of the patron saints of England and London: the Cross of St George with the symbol of the martyrdom of Saint Paul.[45][46] The sword is often erroneously supposed to commemorate the killing of Peasants' Revolt leader Wat Tyler by Lord Mayor of London William Walworth. However the arms were in use some months before Tyler's death, and the tradition that Walworth's dagger is depicted may date from the late 17th century.[45][47][48][49]

The Latin motto of the city is "Domine dirige nos", which translates as "Lord, direct us". It is thought to have been adopted in the 17th century, as the earliest record of it is in 1633.[46][48]

A banner of the arms (the design on the shield) is flown as a flag.

Geography

The City of London is the smallest ceremonial county of England by area and population, and the fourth most densely populated. Of the 326 English districts, it is the second smallest by population, after the Isles of Scilly, and the smallest by area. It is also the smallest English city by population (and in Britain, only two cities in Wales are smaller), and the smallest in the UK by area.

The elevation of the City ranges from sea level at the Thames to 21.6 metres (71 ft) at the junction of High Holborn and Chancery Lane.[50] Two small but notable hills are within the historic core, Ludgate Hill to the west and Cornhill to the east. Between them ran the Walbrook, one of the many "lost" rivers or streams of London (another is the Fleet).

Boundary

Beginning in the west, where the City borders Westminster, the boundary crosses the Victoria Embankment from the Thames, passes to the west of Middle Temple, then turns for a short distance along the Strand and near Temple Bar then north up Chancery Lane, where it borders Camden. It turns east along Holborn to Holborn Circus and then goes northeast to Charterhouse Street. As it crosses Farringdon Road it becomes the boundary with Islington. It continues to Aldersgate, goes north, and turns east into some back streets soon after Aldersgate becomes Goswell Road, since 1994 embracing all of the corporation's Golden Lane Estate. Here, at Baltic Street West, is the most northerly extent. The boundary includes all of the Barbican Estate and continues east along Ropemaker Street and its continuation on the other side of Moorgate, becomes South Place. It goes north, reaching the border with Hackney, then east, north, east on back streets, with Worship Street forming a northern boundary, so as to include the Broadgate estate. The boundary then turns south at Norton Folgate and becomes the border with Tower Hamlets. It continues south into Bishopsgate, and takes some backstreets to Middlesex Street (Petticoat Lane) where it continues south-east then south. It then turns south-west, crossing the Minories so as to exclude the Tower of London, and then reaches the Thames.

The boundary then runs up the centre of the low-tide channel of the Thames, with the exception that Blackfriars Bridge (including the river beneath and land at its south end) is entirely part of the City, making the City and Borough of Richmond upon Thames the only London districts to span north and south of the river. The span and southern abutment of London Bridge is part of the city for some purposes[51] (and as such is part of Bridge ward).[52]

The boundaries are marked by black bollards bearing the city's emblem, and by dragon boundary marks at major entrances, such as Holborn and the south end of London Bridge. A more substantial monument marks the boundary at Temple Bar on Fleet Street.

In some places, the financial district extends slightly beyond the boundaries, notably to the north and east, into the London boroughs of Tower Hamlets, Hackney and Islington, and informally these locations are regarded as being part of the "Square Mile". Since the 1990s the eastern fringe, extending into Hackney and Tower Hamlets, has increasingly been a focus for large office developments due to the availability of large sites compared to within the city.

Gardens and public art

The city has no sizeable parks within its boundary, but does have a network of a large number of gardens and small open spaces, many of them maintained by the corporation. These range from formal gardens such as the one in Finsbury Circus, containing a bowling green and bandstand, to churchyards such as St Olave Hart Street, to water features and artwork in courtyards and pedestrianised lanes.[53]

Gardens include:

- Barber-Surgeon's Hall Garden, London Wall

- Cleary Garden, Queen Victoria Street[54]

- Finsbury Circus, Blomfield Street/London Wall/Moorgate

- Jubilee Garden, Houndsditch

- Portsoken Street Garden, Portsoken Street/Goodman's Yard

- Postman's Park, Little Britain

- Seething Lane Garden, Seething Lane

- St Dunstan-in-the-East, St Dunstan's Hill

- St Mary Aldermanbury, Aldermanbury

- St Olave Hart Street churchyard, Seething Lane

- St Paul's churchyard, St Paul's Cathedral

- West Smithfield Garden, West Smithfield

- Whittington Gardens, College Street

There are a number of private gardens and open spaces, often within courtyards of the larger commercial developments. Two of the largest are those of the Inner Temple and Middle Temple Inns of Court, in the far southwest.

The Thames and its riverside walks are increasingly being valued as open space and in recent years efforts have been made to increase the ability for pedestrians to access and walk along the river.

Climate

The nearest weather station has historically been the London Weather Centre at Kingsway/ Holborn, although observations ceased in 2010. Now St. James Park provides the nearest official readings.

The city has an oceanic climate (Köppen "Cfb") modified by the urban heat island in the centre of London. This generally causes higher night-time minima than outlying areas. For example, the August mean minimum[55] of 14.7 °C (58.5 °F) compares to a figure of 13.3 °C (55.9 °F) for Greenwich[56] and Heathrow[57] whereas is 11.6 °C (52.9 °F) at Wisley[58] in the middle of several square miles of Metropolitan Green Belt. All figures refer to the observation period 1971–2000.

Accordingly, the weather station holds the record for the UK's warmest overnight minimum temperature, 24.0 °C (75.2 °F), recorded on 4 August 1990.[59] The maximum is 37.6 °C (99.7 °F), set on 10 August 2003.[60] The absolute minimum[61] for the weather station is a mere −8.2 °C (17.2 °F), compared to readings around −15.0 °C (5.0 °F) towards the edges of London. Unusually, this temperature was during a windy and snowy cold spell (mid-January 1987), rather than a cold clear night—cold air drainage is arrested due to the vast urban area surrounding the city.

The station holds the record for the highest British mean monthly temperature,[62] 24.5 °C (76.1 °F) (mean maximum 29.2 °C (84.6 °F), mean minimum 19.7 °C (67.5 °F) during July 2006). However, in terms of daytime maximum temperatures, Cambridge NIAB[63] and Botanical Gardens[64] with a mean maximum of 29.1 °C (84.4 °F), and Heathrow[65] with 29.0 °C (84.2 °F) all exceeded this.

| Climate data for London Weather Centre 1971–2000, 43 m asl | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8.3 (46.9) |

8.5 (47.3) |

11.1 (52.0) |

13.5 (56.3) |

17.1 (62.8) |

20.0 (68.0) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.5 (72.5) |

19.3 (66.7) |

15.3 (59.5) |

11.2 (52.2) |

9.1 (48.4) |

14.9 (58.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.7 (38.7) |

3.4 (38.1) |

5.0 (41.0) |

6.4 (43.5) |

9.4 (48.9) |

12.3 (54.1) |

14.6 (58.3) |

14.7 (58.5) |

12.5 (54.5) |

9.6 (49.3) |

6.2 (43.2) |

4.7 (40.5) |

8.5 (47.4) |

| Source: yr.no[66] | |||||||||||||

Public services

Police and security

The city is a police area and has its own police force, the City of London Police, separate from the Metropolitan Police Service covering the majority of Greater London. The City Police previously had three police stations, at Snow Hill, Wood Street and Bishopsgate. They now only retain Bishopsgate along with an administrative headquarters at Guildhall Yard East.[67] The force comprises 735 police officers including 273 detectives.[68] It is the smallest territorial police force in England and Wales, in both geographic area and the number of police officers.

Where the majority of British police forces have silver-coloured badges, those of the City of London Police are black and gold featuring the City crest. The force has rare red and white chequered cap bands and unique red and white striped duty arm bands on the sleeves of the tunics of constables and sergeants (red and white being the colours of the city), which in most other British police forces are black and white. City police sergeants and constables wear crested custodian helmets whilst on foot patrol. These helmets do not feature either St Edward's Crown or the Brunswick Star, which are used on most other police helmets in England and Wales.

The city's position as the United Kingdom's financial centre and a critical part of the country's economy, contributing about 2.5% of the UK's gross national product,[69] has resulted in it becoming a target for political violence. The Provisional IRA exploded several bombs in the early 1990s, including the 1993 Bishopsgate bombing.

The area is also spoken of as a possible target for al-Qaeda. For instance, when in May 2004 the BBC's Panorama programme examined the preparedness of Britain's emergency services for a terrorist attack on the scale of the 11 September 2001 attacks, they simulated a chemical explosion on Bishopsgate in the east of the city. The "Ring of Steel" was established in the wake of the IRA bombings to guard against terrorist threats.

Fire brigade

The city has fire risks in many historic buildings, including St Paul's Cathedral, Old Bailey, Mansion House, Smithfield Market, the Guildhall, and also in numerous high-rise buildings. There is one London Fire Brigade station in the city, at Dowgate, with one pumping appliance.[70] The City relies upon stations in the surrounding London boroughs to support it at some incidents. The first fire engine is in attendance in roughly five minutes on average, the second when required in a little over five and a half minutes.[70] There were 1,814 incidents attended in the City in 2006/2007—the lowest in Greater London. No-one died in an event arising from a fire in the four years prior to 2007.[70]

Power

There is power station located in Charterhouse Street that also provides heat to some of the surrounding buildings.[71]

Demography

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1801 | 130,117 | — |

| 1811 | 122,924 | −5.5% |

| 1821 | 127,040 | +3.3% |

| 1831 | 125,353 | −1.3% |

| 1841 | 127,514 | +1.7% |

| 1851 | 132,734 | +4.1% |

| 1861 | 108,078 | −18.6% |

| 1871 | 83,421 | −22.8% |

| 1881 | 58,764 | −29.6% |

| 1891 | 43,882 | −25.3% |

| 1901 | 32,649 | −25.6% |

| 1911 | 24,292 | −25.6% |

| 1921 | 19,564 | −19.5% |

| 1931 | 15,758 | −19.5% |

| 1941 | 10,920 | −30.7% |

| 1951 | 7,568 | −30.7% |

| 1961 | 5,718 | −24.4% |

| 1971 | 4,325 | −24.4% |

| 1981 | 4,603 | +6.4% |

| 1991 | 3,861 | −16.1% |

| 2001 | 7,186 | +86.1% |

| 2011 | 7,375 | +2.6% |

| 2021 | 8,600 | +16.6% |

| Sources: Office for National Statistics[72] | ||

The Office for National Statistics recorded the population in 2011 as 7,375;[73] slightly higher than in the previous census, 2001,[74] and estimates the population as at mid-2016 to be 9,401. At the 2001 census the ethnic composition was 84.6% White, 6.8% South Asian, 2.6% Black, 2.3% Mixed, 2.0% Chinese and 1.7% were listed as "other".[74] To the right is a table showing the change in population since 1801, based on decadal censuses. The first half of the 19th century shows a population of between 120,000 and 140,000, decreasing dramatically from 1851 to 1991, with a small increase between 1991 and 2001. The only notable boundary change since the first census in 1801 occurred in 1994.

The city's full-time working residents have much higher gross weekly pay than in London and Great Britain (England, Wales and Scotland): £773.30 compared to £598.60 and £491.00 respectively.[75] There is a large inequality of income between genders (£1,085.90 in men compared to £653.50 in women), and this can be explained by job type and length of employment respectively.[75] The 2001 Census showed the city as a unique district amongst 376 districts surveyed in England and Wales.[74] The city had the highest proportional population increase, one-person households, people with qualifications at degree level or higher and the highest indications of overcrowding.[74] It recorded the lowest proportion of households with cars or vans, people who travel to work by car, married couple households and the lowest average household size: just 1.58 people.[74] It also ranked highest within the Greater London area for the percentage of people with no religion and people who are employed.[74]

Ethnicity

| Ethnic Group | Year | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1981 estimations[76] | 1991[77] | 2001[78] | 2011[79] | 2021[80] | ||||||

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| White: Total | 3,732 | 95.5% | 3,840 | 92.7% | 6,075 | 84.6% | 5,799 | 78.5% | 5,955 | 69.4% |

| White: British | – | – | – | – | 4,909 | 68.3% | 4,243 | 57.5% | 3,649 | 42.5% |

| White: Irish | – | – | – | – | 241 | % | 180 | 2.4% | 185 | 2.2% |

| White: Gypsy or Irish Traveller | – | – | – | – | 3 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | ||

| White: Roma | – | – | 59 | 0.7% | ||||||

| White: Other | – | – | – | – | 925 | 12.8% | 1,373 | 18.6% | 2,062 | 24.0% |

| Asian or Asian British: Total | – | – | 217 | 5.2% | 638 | 8.9% | 940 | 12.5% | 1,445 | 16.7% |

| Asian or Asian British: Indian | – | – | 69 | 1.7% | 159 | 2.2 % | 216 | 2.9% | 321 | 3.7% |

| Asian or Asian British: Pakistani | – | – | 20 | 0.5% | 23 | 0.3 % | 16 | 0.2% | 33 | 0.4% |

| Asian or Asian British: Bangladeshi | – | – | 9 | – | 276 | 3.8 % | 232 | 3.1% | 287 | 3.3% |

| Asian or Asian British: Chinese | – | – | 56 | 1.3% | 147 | 2 % | 263 | 3.5% | 545 | 6.3% |

| Asian or Asian British: Other Asian | – | – | 63 | 1.5% | 33 | % | 213 | 2.8% | 259 | 3.0% |

| Black or Black British: Total | – | – | 38 | 0.9% | 184 | 2.6% | 193 | 2.5% | 232 | 2.7% |

| Black or Black British: African | – | – | 12 | 0.3% | 117 | 1.6 % | 98 | 1.3% | 153 | 1.8% |

| Black or Black British: Caribbean | – | – | 12 | 0.3% | 51 | % | 46 | 0.6% | 54 | 0.6% |

| Black or Black British: Other Black | – | – | 14 | 0.3% | 16 | % | 49 | 0.6% | 25 | 0.3% |

| Mixed or British Mixed: Total | – | – | – | – | 163 | 2.3% | 289 | 3.8% | 470 | 5.5% |

| Mixed: White and Black Caribbean | – | – | – | – | 33 | % | 38 | 0.5% | 53 | 0.6% |

| Mixed: White and Black African | – | – | – | – | 16 | % | 37 | 0.5% | 49 | 0.6% |

| Mixed: White and Asian | – | – | – | – | 57 | % | 111 | 1.5% | 179 | 2.1% |

| Mixed: Other Mixed | – | – | – | – | 57 | % | 103 | 1.3% | 189 | 2.2% |

| Other: Total | – | – | 47 | 1.1% | 125 | 1.7% | 154 | 2% | 482 | 5.6% |

| Other: Arab | – | – | – | – | 69 | 0.9% | 114 | 1.3% | ||

| Other: Any other ethnic group | – | – | 47 | 1.1% | 125 | 1.7 % | 85 | 1.1% | 368 | 4.3% |

| Ethnic minority: Total | 177 | 4.5% | 302 | 7.3% | 1,110 | 15.4% | 1,576 | 21.5% | 2,629 | 30.6% |

| Total | 3,909 | 100% | 4,142 | 100% | 7,185 | 100% | 7,375 | 100% | 8584 | 100% |

Economy

The City of London vies with New York City's Lower Manhattan for the distinction of the world's pre-eminent financial centre. The London Stock Exchange (shares and bonds), Lloyd's of London (insurance) and the Bank of England are all based in the city.[81] Over 500 banks have offices in the city. The Alternative Investment Market, a market for trades in equities of smaller firms, is a recent development. In 2009, the City of London accounted for 2.4% of UK GDP.[14]

London's foreign exchange market has been described by Reuters as 'the crown jewel of London's financial sector'.[82] Of the $3.98 trillion daily global turnover, as measured in 2009, trading in London accounted for around $1.85 trillion, or 46.7% of the total.[14] The pound sterling, the currency of the United Kingdom, is globally the fourth-most traded currency[83] and the fourth most held reserve currency.[84]

Canary Wharf, a few miles east of the City in Tower Hamlets, which houses many banks and other institutions formerly located in the Square Mile, has since 1991 become another centre for London's financial services industry. Although growth has continued in both locations, and there have been relocations in both directions, the Corporation has come to realise that its planning policies may have been causing financial firms to choose Canary Wharf as a location.

In 2022, 12.3% of City of London residents had been granted non-domicile status in order to avoid their paying tax in the UK.[85]

Headquarters

Many major global companies have their headquarters in the city, including Aviva,[86] BT Group,[87] Lloyds Banking Group,[88] Quilter, Prudential,[89] Schroders,[90] Standard Chartered,[91] and Unilever.[92]

A number of the world's largest law firms are headquartered in the city, including four of the "Magic Circle" law firms (Allen & Overy, Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, Linklaters and Slaughter & May), as well as other firms such as Ashurst LLP, DLA Piper, Eversheds Sutherland, Herbert Smith Freehills and Hogan Lovells.

Other sectors

Whilst the financial sector, and related businesses and institutions, continue to dominate, the economy is not limited to that sector. The legal profession has a strong presence, especially in the west and north (i.e., towards the Inns of Court). Retail businesses were once important, but have gradually moved to the West End of London, though it is now Corporation policy to encourage retailing in some locations, for example at Cheapside near St Paul's. The city has a number of visitor attractions, mainly based on its historic heritage as well as the Barbican Centre and adjacent Museum of London, though tourism is not at present a major contributor to the city's economy or character. The city has many pubs, bars and restaurants, and the "night-time" economy does feature in the Bishopsgate area, towards Shoreditch. The meat market at Smithfield, wholly within the city, continues to be one of London's main markets (the only one remaining in central London) and the country's largest meat market. In the east is Leadenhall Market, a fresh food market that is also a visitor attraction.

Retail and residential

The trend for purely office development is beginning to reverse as the Corporation encourages residential use, albeit with development occurring when it arises on windfall sites. The city has a target of 90 additional dwellings per year.[93] Some of the extra accommodation is in small pre-World War II listed buildings, which are not suitable for occupation by the large companies which now provide much of the city's employment. Recent residential developments include "the Heron", a high-rise residential building on the Milton Court site adjacent to the Barbican, and the Heron Plaza development on Bishopsgate is also expected to include residential parts.

Since the 1990s, the City has diversified away from near exclusive office use in other ways. For example, several hotels and the first department store opened in the 2000s. A shopping centre was more recently opened at One New Change, Cheapside (near St Paul's Cathedral) in October 2010, which is open seven days a week. However, large sections remain quiet at weekends, especially in the eastern section, and it is quite common to find shops, pubs and cafes closed on these days.

Landmarks

Historic buildings

Fire, bombing and post-World War II redevelopment have meant that the city, despite its history, has fewer intact historic structures than one might expect. Nonetheless, there remain many dozens of (mostly Victorian and Edwardian) fine buildings, typically in historicist and neoclassical style. They include the Monument to the Great Fire of London ("the Monument"), St Paul's Cathedral, the Guildhall, the Royal Exchange, Dr. Johnson's House, Mansion House and a great many churches, many designed by Sir Christopher Wren, who also designed St Paul's.

Prince Henry's Room and 2 King's Bench Walk are notable historic survivors of heavy bombing of the Temple area, which has largely been rebuilt to its historic form. Another example of a bomb-damaged place having been restored is Staple Inn on Holborn. A few small sections of the Roman London Wall exist, for example near the Tower of London and in the Barbican area. Among the twentieth-century listed buildings are Bracken House, the first post World War II buildings in the country to be given statutory protection, and the whole of the Barbican and Golden Lane Estate.

The Tower of London is not in the city, but is a notable visitor attraction which brings tourists to the southeast of the city. Other landmark buildings with historical significance include the Bank of England, the Old Bailey, the Custom House, Smithfield Market, Leadenhall Market and St Bartholomew's Hospital. Noteworthy contemporary buildings include a number of modern high-rise buildings (see section below) as well as the Lloyd's building.

Skyscrapers and tall buildings

- Completed

A growing number of tall buildings and skyscrapers are principally used by the financial sector. Almost all are situated in the eastern side around Bishopsgate, Leadenhall Street and Fenchurch Street, in the financial core of the city. In the north there is a smaller cluster comprising the Barbican Estate's three tall residential towers and the commercial CityPoint tower. In 2007, the 100 m (328 ft) tall Drapers' Gardens building was demolished and replaced by a shorter tower.

The city's buildings of at least 100 m (328 ft) in height are:

| Rank | Name | Completed | Image | Architect | Use | Height to roof | Floors | Location | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| metres | feet | ||||||||

| 1 | Twentytwo | 2020 |  |

PLP Architects | Office | 278 | 912 | 62 | 22 Bishopsgate |

| 2 | Heron Tower | 2010 |  |

Kohn Pedersen Fox | Office | 230 | 754 | 46 | 110 Bishopsgate |

| 3 | Leadenhall Building | 2014 |  |

Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners | Office | 225 | 737 | 48 | 122 Leadenhall Street |

| 4 | 8 Bishopsgate | 2022 |  |

WilkinsonEyre | Office | 204 | 669 | 51 | 8 Bishopsgate |

| 5 | The Scalpel | 2018 |  |

Kohn Pedersen Fox | Office | 190 | 630 | 39 | 52 Lime Street |

| 6 | Tower 42 | 1980 |  |

R Siefert & Partners | Office | 183 | 600 | 47 | 25 Old Broad Street |

| 7 | 30 St Mary Axe | 2003 |  |

Foster and Partners | Office | 180 | 590 | 40 | 30 St Mary Axe |

| 8 | 100 Bishopsgate | 2019 |  |

Allies and Morrison | Office | 172 | 563 | 40 | 100 Bishopsgate |

| 9 | Broadgate Tower | 2008 |  |

SOM | Office | 164 | 538 | 35 | 201 Bishopsgate |

| 10 | 20 Fenchurch Street | 2014 |  |

Rafael Viñoly | Office | 160 | 525 | 37 | 20 Fenchurch Street |

| 11 | 40 Leadenhall Street | 2022 |  |

Make Architects | Office | 154 | 505 | 34 | 40 Leadenhall Street |

| 12 | One Bishopsgate Plaza | 2020 |  |

MSMR | Hotel | 135 | 443 | 44 | 150 Bishopsgate |

| 13 | CityPoint[A] | 1967 |  |

F. Milton Cashmore and H. N. W. Grosvenor[94] | Office | 127 | 417 | 36 | 1 Ropemaker Street |

| 14 | Willis Building | 2007 |  |

Foster and Partners | Office | 125 | 410 | 26 | 51 Lime Street |

| =15 | Cromwell Tower | 1973 |  |

Chamberlin, Powell and Bon | Residential | 123 | 404 | 42 | Barbican Estate |

| =15 | Lauderdale Tower | 1974 |  |

Chamberlin, Powell and Bon | Residential | 123 | 404 | 42 | Barbican Estate |

| =15 | Shakespeare Tower | 1976 |  |

Chamberlin, Powell and Bon | Residential | 123 | 404 | 42 | Barbican Estate |

| 18 | St. Helen's | 1969 |  |

GMW Architects | Office | 118 | 387 | 28 | 1 Undershaft |

| 19 | The Heron | 2013 |  |

David Walker Architects | Residential | 112 | 367 | 35 | Milton Court |

| 20 | St Paul's Cathedral | 1710 |  |

Sir Christopher Wren | Cathedral | 111 | 365 | n/a | Ludgate Hill |

| 21 | 99 Bishopsgate | 1976 |  |

GMW Architects | Office | 104 | 340 | 26 | 99 Bishopsgate |

| 22 | One Angel Court | 2017 |  |

Fletcher Priest | Office | 101 | 331 | 24 | 1 Angel Court |

| 23 | Stock Exchange Tower | 1970 |  |

Richard Llewelyn-Davies, Baron Llewelyn-Davies, Weeks, Forestier-Walker and Bar | Office | 100 | 328 | 27 | 125 Old Broad Street |

- ^ CityPoint was originally completed in 1967 and named Britannic House standing at 122 m tall, but was refurbished in 2000 and increased to 127 m in height.

- Timeline

The timeline of the tallest building in the city is as follows:

| Name |

Years as tallest |

Height to roof (m) |

Height to roof (ft) |

Floors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Twentytwo | 2019–present | 278 | 912 | 62 |

| Heron Tower | 2010–2019 | 230 | 754 | 46 |

| Tower 42 | 1980–2010 | 183 | 600 | 47 |

| CityPoint | 1967–1980 | 122 | 400 | 35 |

| St Paul's Cathedral | 1710–1967 | 111 | 365 | n/a |

| St Mary-le-Bow | 1683–1710 | 72 | 236 | n/a |

| Monument to the Great Fire of London | 1677–1683 | 62 | 202 | n/a |

| Old St Paul's Cathedral | 1310–1677 | 150 | 493 | n/a |

Transport

Rail and Tube

The city is well served by the London Underground ("tube") and National Rail networks.

Seven London Underground lines serve the city; the underground stations include:[95]

- Aldgate

- Bank and Monument

- Barbican

- Blackfriars

- Cannon Street

- Chancery Lane

- Liverpool Street

- Mansion House

- Moorgate

- St. Paul's

In addition, Aldgate East (

), Farringdon (

), Farringdon (

), Temple (

), Temple (

) and Tower Hill (

) and Tower Hill (

) tube stations are all situated within metres of the City of London boundary.[95]

) tube stations are all situated within metres of the City of London boundary.[95]

The Docklands Light Railway (DLR  ) has two termini in the city: Bank and Tower Gateway. The DLR links the City directly to the East End. Destinations include Canary Wharf and London City Airport.[95][96]

) has two termini in the city: Bank and Tower Gateway. The DLR links the City directly to the East End. Destinations include Canary Wharf and London City Airport.[95][96]

The Elizabeth line (constructed by the Crossrail project) runs east–west underneath the City of London. The line serves two stations in the City – Farringdon and Liverpool Street – which additionally serves the Barbican and Moorgate areas. Elizabeth line services link the City directly to destinations such as Canary Wharf, Heathrow Airport, and the M4 Corridor high-technology hub (serving Slough and Reading).[97]

The city is served by a frequent Thameslink rail service which runs north–south through London. Thameslink services call at Farringdon, City Thameslink, and London Blackfriars. This provides the city with a direct link to key destinations across London, including Elephant & Castle, London Bridge, and St Pancras International (for the Eurostar to mainland Europe). There are also regular, direct trains from these stations to major destinations across East Anglia and the South East, including Bedford, Brighton, Cambridge, Gatwick Airport, Luton Airport, and Peterborough.[98]

There are several "London Terminals"[98][99] in the city:

- London Blackfriars – Thameslink services and some Southeastern services to South East London and Kent.

- London Cannon Street – Southeastern services to South East London and Kent.

- London Fenchurch Street – C2c services along the Thames Estuary towards East London, south Essex, and Southend.

- London Liverpool Street – Greater Anglia and some C2c services towards destinations in East London and East Anglia, including Stratford, Cambridge, Chelmsford, Ipswich, Norwich, Southend, and Southend Airport. Stansted Express to Stansted Airport. London Overground (

)[100] to destinations in north and east London including Hackney Downs, Seven Sisters, Walthamstow, Chingford, Enfield, and Cheshunt.

)[100] to destinations in north and east London including Hackney Downs, Seven Sisters, Walthamstow, Chingford, Enfield, and Cheshunt. - Moorgate – Great Northern towards Finsbury Park, Enfield, and other destinations in North London and Hertfordshire, including Hertford and Welwyn Garden City.

All stations in the city are in London fare zone 1.[95]

Road

The national A1, A10 A3, A4, and A40 road routes begin in the city. The city is in the London congestion charge zone, with the small exception on the eastern boundary of the sections of the A1210/A1211 that are part of the Inner Ring Road. The following bridges, listed west to east (downstream), cross the River Thames: Blackfriars Bridge, Blackfriars Railway Bridge, Millennium Bridge (footbridge), Southwark Bridge, Cannon Street Railway Bridge and London Bridge; Tower Bridge is not in the city. The city, like most of central London, is well served by buses, including night buses. Two bus stations are in the city, at Aldgate on the eastern boundary with Tower Hamlets, and at Liverpool Street by the railway station. However although the London Road Traffic Act 1924 removed from existing local authorities the powers to prevent the development of road passengers transport services within the London Metropolitan Area, the City of London retained most such powers. As a consequence, neither Trolleybus nor Green Line Coach services were permitted to enter the City to pick up or set down passengers. Hence the building of Aldgate (Minories) Trolleybus and Coach station as well as the complex terminal arrangements at Parliament Hill Fields. This restriction was removed by the Transport Act 1985

Cycling

Cycling infrastructure in the city is maintained by the City of London Corporation and Transport for London (TfL).[102]

- Cycle Superhighway 1 runs from Tottenham to the city. It is a signposted cycle route, passing through Stoke Newington and Hackney before entering the City south of Old Street.

- Cycle Superhighway 2 runs from Stratford to the city, via Bow, Mile End, and Whitechapel. The route enters the city near Aldgate. The route runs primarily on segregated cycle track.

- Cycleway 3 is an east–west bike freeway through the city. The route runs along the southern rim of the city, following the route of the Thames. Eastbound, Cycleway 3 provides cyclists with a direct, signposted cycle link to Shadwell, Poplar and Canary Wharf, and Barking. The route runs Westbound on traffic-free track to Lancaster Gate via Parliament Square, Buckingham Palace, and Hyde Park.

- Cycleway 6 runs north–south through the city on traffic-free cycle track. The track passes Farringdon Station, the Holborn Viaduct, Ludgate Circus, Blackfriars station, and Blackfriars Bridge. Northbound, the route passes through Clerkenwell, Bloomsbury, King's Cross, and Kentish Town. The route southbound carries cyclists to Elephant and Castle.

- Cycle Superhighway 7 begins in the City at an interchange with Cycleway 3. It leaves the City over Southwark Bridge and provides cyclists with an unbroken, signposted route to Colliers Wood via Elephant and Castle, Clapham, and Tooting, amongst other destinations.

- Quietway 11 is a northbound continuation of Cycleway 7. It is a signposted cycle route which runs from Southwark Bridge to Hoxton, via the Barbican and Moorgate.

The Sandander Cycles and Beryl bike sharing systems operate in the City of London.[102][103]

River

One London River Services pier is on the Thames in the city, Blackfriars Millennium Pier, though the Tower Millennium Pier lies adjacent to the boundary near the Tower of London. One of the Port of London's 25 safeguarded wharves, Walbrook Wharf, is adjacent to Cannon Street station, and is used by the corporation to transfer waste via the river. Swan Lane Pier, just upstream of London Bridge, is proposed to be replaced and upgraded for regular passenger services, planned to take place in 2012–2015. Before then, Tower Pier is to be extended.[104]

There is a public riverside walk along the river bank, part of the Thames Path, which opened in stages – the route within the city was completed by the opening of a stretch at Queenhithe in 2023.[105] The walk along Walbrook Wharf is closed to pedestrians when waste is being transferred onto barges.

Travel to work (by residents)

According to a survey conducted in March 2011, the methods by which employed residents 16–74 get to work varied widely: 48.4% go on foot; 19.5% via light rail, (i.e. the Underground, DLR, etc.); 9.2% work mainly from home; 5.8% take the train; 5.6% travel by bus, minibus, or coach; and 5.3% go by bicycle; with just 3.4% commuting by car or van, as driver or passenger.[106]

Education

The city is home to a number of higher education institutions including: the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, the Cass Business School, The London Institute of Banking & Finance and parts of three of the universities in London: the Maughan Library of King's College London on Chancery Lane, the business school of London Metropolitan University, and a campus of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. The College of Law has its London campus in Moorgate. Part of Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry is on the Barts hospital site at West Smithfield.

The city has only one directly maintained primary school, The Aldgate School (formerly Sir John Cass's Foundation Primary School) at Aldgate[107] (ages 4 to 11). It is a Voluntary-Aided (VA) Church of England school, maintained by the Education Service of the City of London.

City residents send their children to schools in neighbouring Local Education Authorities, such as Islington, Tower Hamlets, Westminster and Southwark.

The City controls three independent schools, City of London School (a boys' school) and City of London School for Girls in the city, and the City of London Freemen's School (co-educational day and boarding) in Ashtead, Surrey. The City of London School for Girls and City of London Freemen's School have their own preparatory departments for entrance at age seven. It is the principal sponsor of The City Academy, Hackney, City of London Academy Islington, and City of London Academy, Southwark.[108]

Public libraries

Libraries operated by the Corporation include three lending libraries; Barbican Library, Shoe Lane Library and Artizan Street Library and Community Centre. Membership is open to all – with one official proof of address required to join.

Guildhall Library, and City Business Library are also public reference libraries, specialising in the history of London and business reference resources.[109]

Money laundering

The City of London's role in illicit financial activity such as money laundering has earned the financial hub sobriquets such as 'The Laundromat' and 'Londongrad'.[110]

London's role as the world's dirty money clearing house is well-documented but efforts are being made to clean up through legislation, e.g. authorising unexplained wealth orders. High-value properties are sought after by criminals and money launderers legitimising their gains by investing in the city's prestigious real estate.[111][112][113]

In May 2024, the UK's then deputy foreign secretary, Andrew Mitchell, said that 40% of the dirty money in the world goes through the City of London and other crown dependencies.[114]

See also

- City of London Corporation

- City of London School

- City of London Freemen's School

- List of churches in the City of London

- List of areas of London

- Londinium

- Street names of the City of London

Notes

- ^ The City of London is a sui generis unit of local government, referred by the Ordnance Survey as the City and County of the City of London[1] to distinguish it as such on their mapping and in their datasets.

References

- ^ "City and County of the City of London". Ordnance Survey. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ Greater London Authority (January 2008). London's Central Business District: Its global importance (PDF). p. 6. ISBN 978-1-84781-109-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ Beckett, JV (2005). City status in the British Isles, 1830–2002. Historical urban studies. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7546-5067-6.

- ^ Mills, AD (2010). Dictionary of London Place Names. Oxford University Press. p. 152.

Of course until relatively recent times the name London referred only to the City of London with even Westminster remaining a separate entity. But when the County of London was created in 1888, the name often came to be rather loosely used for this much larger area, which was also sometimes referred to as Greater London from about this date. However, in 1965 Greater London was newly defined as a much enlarged area.

- ^ "City of London Resident Population Census 2001" (PDF). Corporation of London. July 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 June 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2009.

- ^ Roberts, Richard (2008). The City: A Guide to London's Global Financial Centre. Economist. ISBN 9781861978585. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "Search". City of London. Archived from the original on 26 February 2024. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ "Lord Mayor Biography". City of London. City of London Corporation. Archived from the original on 20 November 2021. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ "Global Financial Centres 7" (PDF). Z/Yen. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- ^ Dunton, Larkin (1896). The World and Its People. Silver, Burdett. p. 24.

- ^ "How life has changed in the City of London: Census 2021". Archived from the original on 12 October 2023. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ UK Census (2021). "2021 Census Area Profile – City of London (E09000001)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ "Statistics about the City – City of London". www.cityoflondon.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ a b c "City of London Jobs" (PDF). The City of London. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ Wallace, Leslie (2015). Late pre-Roman Iron Age (LPRIA). Cambridge University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-107-04757-0. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- ^ Ghosh, Pallab (23 November 2015). "DNA study finds London was ethnically diverse from start". BBC News. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ Bede (1969). Colgrave, Bertram; Mynors, R. A. B. (eds.). Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Oxford: Clarendon. pp. 142–3.

- ^ Asser's Life of King Alfred, ch. 83, trans. Simon Keynes and Michael Lapidge, Alfred the Great: Asser's Life of King Alfred & Other Contemporary Sources (Penguin Classics) (1984), pp. 97–8.

- ^ Vince, Alan, Saxon London: An Archaeological Investigation, The Archaeology of London series (1990).

- ^ London: The Biography, 2000, Peter Ackroyd, p. 33–35

- ^ A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 2. London: Victoria County History. 1911. pp. 15–60. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ Tatlock, J. S. P. (October 1936). "The Date of Henry I's Charter to London". Speculum. 11 (4): 461–469. doi:10.2307/2848538. JSTOR 2848538. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ "The City of London's strange history". 29 September 2014. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ "Museum of London". City of London.

- ^ The City of London: A History. Borer, Mary Irene Cathcart: New York, D. McKay Co., 1978 ISBN 0-09-461880-1 p. 112.

- ^ "Local Government Bill". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 13 February 1963. col. 278–291. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015. Archived 14 October 2023 at the Wayback Machine Michael Stewart, (L, Fulham

- ^ City of London Corporation Archived 27 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine Ward Motes

- ^ City of London Corporation Archived 12 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Ward Boundaries, Beadles and Clubs

- ^ Guildhall Library Manuscripts Section Archived 28 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine City of London wards

- ^ Bridge Ward Club Archived 23 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine History of the Bridge wards

- ^ Corporation of London Archived 14 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine Ward Boundary Review (2010)

- ^ Sillitoe, Neil (14 April 2008). "Neighbourhood Statistics". Archived from the original on 11 February 2003. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- ^ René Lavanchy (12 February 2009). "Labour runs in City of London poll against 'get-rich' bankers". The Express Tribune. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- ^ "City of London (Ward Elections) Bill (By Order) – Second Reading". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 24 February 1999. col. 482–485. Archived from the original on 4 February 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ Shaxson, N. (2011). Treasure islands: Tax havens and the men who stole the world. London: The Bodley Head.

- ^ "HMSO City of London (Ward Elections) Act 2002 (2002 Chapter vi)". Government of the United Kingdom. 21 October 2011. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ Association for Geographic Information What place is that then? (PDF)

- ^ City of London (Approved Premises for Marriage) Act 1996 Archived 8 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine "By ancient custom the Honourable Society of the Inner Temple and the Honourable Society of the Middle Temple exercise powers within the areas of the Inner Temple and the Middle Temple respectively ("the Temples") concerning (inter alia) the regulation and governance of the Temples"

- ^ Middle Temple Archived 30 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine as a local authority

- ^ "Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act 2011". Government of the United Kingdom. 26 October 2011. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ "London Port Health Authority". Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ "City of London". britishflags.net. Archived from the original on 23 January 2009. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ "The City and London Borough Boundaries Order 1993". Government of the United Kingdom. 4 July 2011. Archived from the original on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ Briggs, Geoffrey (1971). Civic and Corporate Heraldry: A Dictionary of Impersonal Arms of England, Wales and Northern Ireland. London: Heraldry Today. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-900455-21-6.

- ^ a b c Beningfield, Thomas James (1964). London, 1900–1964: Armorial bearings and regalia of the London County Council, the Corporation of London and the Metropolitan Boroughs. Cheltenham and London: J Burrow & Co Ltd. pp. 21–23.

- ^ a b c "The City Arms" (PDF). Corporation of London Records Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ Scott-Giles, C. Wilfrid (1953). Civic Heraldry of England and Wales, 2nd edition. London: J. M. Dent & Sons. pp. 245–246.

- ^ a b Fox-Davies, A. C. (1915). The Book of Public Arms (2 ed.). London: T. C. & E. C. Jack. pp. 456–458. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ Crosley, Richard (1928). London's Coats of Arms and the Stories They Tell. London: Robert Scott. pp. 14–21.

- ^ Ordnance Survey data

- ^ London Bridge Act 1967 section 35

- ^ City of London Corporation Interactive maps (Electoral services: Ward boundaries)

- ^ "Gardens of the City of London". Gardens of the City of London. Archived from the original on 15 November 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ "The History of the Bay Trust, Fred Cleary – Founder". baytrust.org.uk. 2013. Archived from the original on 9 January 2014. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ "Aug Min". YR.NO. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ^ "Aug Min". MetOffice. Archived from the original on 28 June 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ^ "Aug Min". MetOffice. Archived from the original on 24 December 2010. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ^ "Aug Min". MetOffice. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ^ "Aug 1990 Min". Tutiempo. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ^ "Aug 2003 Max". Tutiempo. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ^ "Jan 1987 Min". Tutiempo. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ^ "Jul 2006 Mean". Tutiempo. Archived from the original on 5 October 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2011.