Also see the Post Office building near Bank.

General Post Office

Wikipedia

This text was copied from Wikipedia on 24 December 2024 at 5:10AM.

| |

Victorian 'Post Office' pillar box in Oxton, Merseyside. | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 31 July 1635 (1635-07-31) (public service) 29 December 1660 (1660-12-29) (Post Office Act 1660) |

| Dissolved | 1 October 1969 (1969-10-01) |

| Superseding agency | |

| Jurisdiction |

|

| Headquarters | General Post Office, St Martin's le Grand, London EC2 |

| Agency executives |

|

| Parent agency | HM Government |

The General Post Office (GPO)[1] was the state postal system and telecommunications carrier of the United Kingdom until 1969.[2] Established in England in the 17th century, the GPO was a state monopoly covering the dispatch of items from a specific sender to a specific receiver (which was to be of great importance when new forms of communication were invented); it was overseen by a Government minister, the Postmaster General. Over time its remit was extended to Scotland and Ireland, and across parts of the British Empire.

The GPO was abolished by the Post Office Act 1969, which transferred its assets to the Post Office, so changing it from a Department of State to a statutory corporation. Responsibility for telecommunications was given to Post Office Telecommunications, the successor of the GPO Telegraph and Telephones department. In 1980, the telecommunications and postal sides were split prior to British Telecommunications' conversion into a totally separate publicly owned corporation the following year as a result of the British Telecommunications Act 1981. In 1986 the Post Office Counters business was made functionally separate from Royal Mail Letters and Royal Mail Parcels (the latter being later rebranded as 'Parcelforce'). At the start of the 21st century the Post Office became a public limited company (initially called 'Consignia plc'), which was renamed 'Royal Mail Group plc' in 2002. In 2012 the counters business (known as 'Post Office Limited' since 2002) was taken out of Royal Mail Group, prior to the latter's privatisation in 2013.[3] The privatised holding company (Royal Mail plc) was renamed International Distributions Services plc in 2022.[4]

Early postal services

In the medieval period, nobles generally employed messengers to deliver letters and other items on their behalf. In the 12th century a permanent body of messengers had been formed within the Royal Household of King Henry I, for the conveyance of royal and official correspondence. The messengers delivered their messages in person, each travelling on his own horse and taking time as needed for rest and refreshment (including stopping overnight if the length of journey required it).[5] Under Edward IV, however, a more efficient system was put in place (albeit temporarily) to aid communications during his war with Scotland: a number of post houses were established at twenty-mile intervals along the Great North Road, between London and Berwick, to provide the king's messengers with fresh horses for each stage of the journey;[notes 1] in this way they were able to travel up to a hundred miles a day.[5]

Under King Henry VIII a concerted effort was made to maintain a regular postal system for the conveyance of royal and government despatches (in times of peace as well as in time of war). To oversee the system, the king appointed Brian Tuke to serve as 'Master of the Postes'. By the 1550s five post roads were in place, connecting London with Dover, Edinburgh, Holyhead (via Chester), Milford Haven (via Bristol) and Plymouth.[5] (A sixth post road, to Norwich via Colchester, would be added in the early 17th century.) Each post-house on the road was staffed by a postmaster, whose main responsibility was to provide the horses; he would also provide a guide to accompany the messenger as far as the next post house (and then see to the return of the horses afterwards). In practice most post-houses were established at roadside inns and the innkeeper served as postmaster (in return for a small salary from the Crown).[6]

At Dover merchant ships were regularly employed to convey letters to and from the continent. A similar system connected Holyhead and Milford to Ireland (and by the end of the 16th century a packet service had been established on the Holyhead to Dublin route).[5] Private citizens could make use of the post-horse network, if they could afford it (in 1583 they had to pay twopence per mile for the horse, plus fourpence per stage for the guide),[6] but it was primarily designed for the relaying of state and royal correspondence, or for the conveyance from one place to another of individuals engaged on official state business (who paid a reduced rate). Private correspondence was often sent using common carriers at this time, or with others who regularly journeyed from place to place (such as travelling pedlars); towns often made use of local licensed carriers, who plied their trade using a horse and cart or waggon, while the universities, along with certain municipal and other corporations, maintained their own correspondence networks.[7]

Many letters went by foot-post rather than on horseback. Footposts or runners were employed by many towns, cities and other communities, and had been for many years.[8] A 16th-century footpost would cover around 30 miles per day, on average.[9] At the time of the Spanish Armada every parish was by royal command required to provide a footpost, and every town a horse-post, to help convey news in the event of an imminent invasion.

By the early 1600s there were two options for couriers using the post system: they could either ride 'through-post', carrying the correspondence the full distance; or they could use the 'post of the packet', whereby the letters were carried by the guides from one post house to the next in a cotton-lined leather bag (although this method was only available for royal, government or diplomatic correspondence).[10] The guides at this time were provided with a post horn, which they had to sound at regular intervals or when encountering others on the road (other road users were expected to give way to the post riders).

Foreign postage

At the start of the 16th century a system for the conveyance of foreign dispatches had been set up, organised by Flemish merchants in the City of London; but in 1558, after a dispute arose between Italian, Flemish and English merchants on the matter, the Master of the King's Posts was granted oversight of it instead.[11] In 1619, James I appointed a separate Postmaster General 'for foreign parts', granting him (and his appointees) the sole privilege of carrying foreign correspondence to and from London.[5] (The separate Postmaster General appointments were consolidated in 1637, but the 'foreign' and 'inland' postal services remained separate in terms of administration and accounting until the mid-19th century).

The General Post

It was not until 1635 that a general or public post was properly established, for inland letters as for foreign ones.[11] On 31 July that year, King Charles I issued a proclamation 'for the settling of the Letter-office of England and Scotland',[12] an event which 'may properly be regarded as the origin of the British post-office'.[7] By this decree, Thomas Witherings (who had been appointed 'Postmaster of England for foreign parts' three years earlier) was empowered to provide for the carriage of private letters at fixed rates 'betwixt London and all parts of His Majesty's dominions'.[5] To this end, the royal proclamation instructed him to establish 'a running post, to run night and day', initially between London and Edinburgh, London and Holyhead and London and Plymouth, 'for the advancement of all His Majesty's subjects in their trade and correspondence'. (A similar system, running between London and Dover, had already been established by Witherings as part of his administration of the foreign posts, and he himself had proposed its extension to the rest of the realm). Witherings was required to extend the new system to other post roads 'as soon as possibly may be' (beginning with the routes to Oxford and Bristol, and to Colchester, Norwich and Yarmouth); and provision was also made for the establishment of 'bye-posts' to run to and from places not directly served by the post road system (such as Lincoln and Hull).[11] The new system was fully and profitably running by 1636.[5]

In order to facilitate the new arrangement, the King commanded 'all his postmasters, upon all the roads of England, to have ready in their stables one or two horses [...] to carry such messengers, with their portmantles, as shall be imployed in the said service', and they were forbidden from hiring out these horses to others on days when the mail was due.[13] Furthermore, it was enjoined that (with a few specific exceptions) 'no other messenger or messengers, footpost or footposts, shall take up, carry, receive or deliver any letter or letters whatsoever, other than the messengers appointed by the said Thomas Witherings',[12] thus establishing a monopoly, which (under the auspices of the Royal Mail) would remain in place until 2006.[14]

Under the Commonwealth the Post Office was farmed to John Manley and John Thurloe, successively. In 1657 an Act of Parliament entitled Postage of England, Scotland and Ireland Settled set up a postal system for the whole of the British Isles (the nations of which had been unified under Oliver Cromwell as a result of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms), stating that 'there shall be one General Post-Office, and one office stiled the Postmaster-Generall of England and Comptroller of the Post-Office'.[11] The Act also reasserted the postal monopoly for letter delivery and for post-horses; and it set new rates both for carriage of letters and for 'riding post'. During the Commonwealth, what had been a weekly post service to and from London was increased to a thrice-weekly service: letters were despatched from the General Letter Office in London every Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday evening, while the inbound post arrived early in the morning on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays.[5] Usually the recipient of the post paid the fee (and had the right to refuse to accept the item if they did not wish to pay); the charge was based on the distance the item had been carried so the Post Office had to keep a separate account for each item.

After the Restoration, the Post Office Act 1660 (12 Cha. 2. c. 35) was passed (the previous Cromwellian Act being void), confirming the arrangements in place for the Post Office, and the post of Postmaster General, and emphasizing the public and economic benefits of a General Post system:[15]

"Whereas for the maintenance of mutual correspondencies, and prevention of many inconveniences happening by private posts, several public post-offices have been heretofore erected for carrying and recarrying of letters by post to and from all parts and places within England, Scotland, and Ireland, and several posts beyond the seas, the well-ordering whereof is a matter of general concernment, and of great advantage, as well for the preservation of trade and commerce as otherwise".

To begin with the Post Office was again farmed, nominally to Henry Bishop, but the deal was bankrolled by John Wildman (a gentleman of dubious repute, who kept a tight rein on his investment). Two years later Wildman was imprisoned, implicated in a plot against the King, whereupon Bishop sold the lease on to the King's gunpowder manufacturer, Daniel O'Neill; after the latter's death, his widow the Countess of Chesterfield served out the remainder of the original seven-year term (so becoming the first female Postmaster General).[16] Meanwhile, under the terms of a 1663 Act of Parliament, the 'rents, issues and profits' of the Post Office had been settled by the King on his brother, the Duke of York, to provide for his support and maintenance.[17] Following the latter's accession to the throne as King James II, this income became part of the hereditary revenues of the Crown; and subsequently, under the growing scrutiny of HM Treasury, the postal service came increasingly to be viewed as a source of government income (as seen in the Post Office (Revenues) Act 1710, which increased postal charges and levied tax on the income in order to finance Britain's involvement in the War of the Spanish Succession).[16]

Distribution and delivery

The distribution network was centred on the General Letter Office in London (which was on Threadneedle Street prior to the Great Fire of London, after which it moved first to Bishopsgate and then to Lombard Street in 1678).[16] The incoming post arrived each week on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays; it was sorted and stamped: London letters went to the 'windows' where members of the public were able to collect them from the office in person (once they had paid the requisite fee), while 'Country letters' were dispatched along the relevant post road. The outgoing post went on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays. Postage was payable by the recipient (rather than the sender) and depended on the length of the letter and the distance it had travelled;[notes 2] each individual charge was calculated in London and entered into a book, which went with the letters on the road, indicating the amounts due from each postmaster for the letters delivered into his care.[16]

At first the new postal network was not especially well publicised;[17] but in his 1673 publication Britannia, Richard Blome sought to remedy this by describing in some detail the geographical disposition of the new 'general Post-Office', which he called an 'exceeding great conveniency' for the inhabitants of the nation.[18] At that time there were 182 Deputy Post-Masters (or 'Deputies') in England [and Wales], most of whom were stationed at the 'Stages' or stops which lay along the six main post-roads;[notes 3] and under them were sub-Post-masters, based at market towns which were not on the main post-roads but to which the service had been extended. (The sub-Post-masters, unlike the Deputies, were not employed by the Post Office.)[17]

The expansion of the service beyond the main post-roads was in no small part due to the enterprise of the Deputy post-masters themselves, who were allowed to profit from branch services which they established and operated. In this way, the network of 'by-posts' greatly expanded in the 1670s:[16] in 1673 Blome could write that 'there is scarce any Market-Town of note [which does not have] the benefit of the conveyance of letters to and fro'; he went on to list, County by County, both the 'Stages' on the post-roads (of which there were over 140) and the Post-towns on the branch roads (which by then numbered over 380 in total), where members of the public were able to leave letters with a Post-Master 'to be sent as directed'.[18] Before long moves were made to incorporate the by-posts (and their income) into the national network: 'Riding Surveyors' were appointed in 1682, to travel with the post and scrutinise the Deputies' income and activity at each Stage (particularly in relation to by-letters); in later years the Surveyors served as the GPO's inspectorate, tasked with maintaining efficiency and consistency across the network (until they were finally disbanded in the 1930s).[16]

It was usual for each postmaster to employ post-boys to ride with the mail bags from one post-house to the next; the postmaster at the next post-house would then record the time of arrival, before transferring the bags to a new horse, ridden by a new post-boy, for the next stage of the journey.[5] On the outbound journey from London, the mail for each Stage (and its associated Post-towns) was left at the relevant post-house. Arrangements for its onward delivery varied somewhat from place to place. Witherings had envisaged using 'foot-posts' for this purpose (in 1620 Justices of the Peace had been ordered to arrange appointment of two to three foot-posts in every parish for the conveyance of letters),[19] though in practice precise details were often left to the local postmaster. On the return journey to London, bags of letters would be picked up from each post-house on the way, and taken to the General Letter Office to be sorted for despatch.

Packet boats and ship letters

With the establishment of a regular public postal service came the need for waterborne mail services (carrying letters to and from Ireland, continental Europe and other destinations) to be placed on a more regular footing. 'Packet boats', offering a regular scheduled mail service, were already in use for the passage between Holyhead and Dublin; but for letters to and from the Continent the post was entrusted to messengers, who would make their own travel arrangements.[5] This was far from reliable, so in the 1630s Thomas Witherings set about establishing a regular Dover-Calais packet service.[5] By the end of the century additional packet services had been established between Harwich (off the Yarmouth post road) and Helvoetsluys, between Dover and Ostend/Nieuport, and between Falmouth and Corunna. The packet services were generally arranged by contract with an agent, who would commit to provide a regular mail-carrying service in exchange for a fee or subsidy.[17] In the following century, packet services out of Falmouth began to sail to the West Indies, North America and other transatlantic destinations.

Packet boats, however, were not the only means of conveying letters overseas: there had always been the option of sending them by merchant ship, and coffee houses had long been accustomed to receiving letters and packages on behalf of ships' captains, who would carry them for a fee. The trade in these 'ship letters' was acknowledged (and legitimised) in the Post Office Acts of 1657 and 1660.[17] Attempts were made to levy Post Office fees on these letters and 'ship letter money' was offered to captains for each letter given to a postmaster on arrival in England in order for these charges to be applied; however they were under no legal obligation to comply and the majority of ship letters evaded the extra charges.

The London Penny Post

In 1680 William Dockwra and Robert Murray founded the 'Penny Post', which enabled letters and parcels to be sent cheaply to and from destinations in and around London. A flat fee of a penny was charged for sending letters or parcels up to a pound in weight within an area comprising the City of London, the City of Westminster and the Borough of Southwark; while two-pence was charged for items posted or delivered in the surrounding 'country' area (which included places such as Hackney, Newington, Lambeth and Islington). The Penny Post letter-carriers operated from seven main sorting offices around London, which were supplemented by between four and five hundred 'receiving houses' in all the principal streets in the area, where members of the public could post items. (Prior to the establishment of the Penny Post, the only location where letters could be posted in London was the General Letter Office in Lombard Street.)[17] The receiving-houses were often found in public houses, coffee houses or other retail premises.[21] Deliveries were made six or eight times a day in central London (and a minimum of four times a day in the outskirts).[11]

The innovation was a great success, and within two years a court ruling obliged the London Penny Post to come under the authority of the Postmaster General. Although now part of the GPO, the London Penny Post continued to operate entirely independently of the General (or 'Inland') Post until 1854 (when the two systems were combined).[11] An attempt by Charles Povey to set up a rival halfpenny post in 1709 was halted after several months' operation; however Povey's practice of having letter-carriers ring a bell to attract custom was adopted by the Post Office and went on to be employed in major cities until the mid-19th century.[17]

In 1761 permission was given for the establishment of penny-post arrangements elsewhere in the realm, to function along the same lines as the London office, if they could be made financially viable; by the end of the century there were penny-post systems operating in Birmingham, Bristol, Dublin, Edinburgh and Manchester (to be joined by Glasgow and Newcastle-upon-Tyne in the 1830s).[5]

In 1801 the cost of posting a letter within the central London area was doubled; thenceforward the London District Post was known as the 'Two-penny Post' until its amalgamation into the General Post 53 years later.[5]

Expansion at home and abroad

During the reign of King William III, the General Post Office created a network of 'receiving-houses', in London and the larger provincial towns, where senders could submit items.[22]

A Scottish Post Office was established in 1695 (although the post-road to Edinburgh continued to be managed from London); in 1710 the Scottish and English establishments were united by statute.[11] By virtue of the same Act of Parliament (the Post Office (Revenues) Act 1710), the functions of the 'general letter office and post office' in the City of London were set out, and the establishment of 'chief letter offices' in Edinburgh, Dublin, New York and the Leeward Islands was enjoined. The Irish post at this time operated as part of the GPO under a Deputy Postmaster General based in Dublin; but in 1784 an Act was passed by the Parliament of Ireland providing for an independent Post Office in Ireland under its own Postmaster General[23] (an arrangement that remained in place until 1831).

The established post roads in Britain ran to and from London. The use of other roads required government permission (for example, it was only after much lobbying that a 'cross-post' between Bristol and Exeter was authorised, in 1698; previously mail between the two cities had to be sent via London).[24] In 1720 Bath postmaster Ralph Allen, who had a vision for improving the situation, took over responsibility for the cross-posts (i.e. routes connecting one post road to another) and bye-posts (connecting to places off the main post roads).[notes 4][25] He greatly expanded the network of post towns served by the General Post, and at the same time did much to reform its workings.

In 1772 the Court of the King's Bench ruled that letters ought to be delivered directly to recipients within the boundaries of each post town at no additional cost. Often a messenger with a locked satchel would be employed by the postmaster to deliver and receive items of mail around town; he would alert people to his presence by ringing a hand bell.[21] While postmasters were not obliged to deliver items to places outside the boundary, they could agree to do so on payment of an extra fee.

New modes of transport

Road

In the 1780s, Britain's General Post network was revolutionised by theatrical impresario John Palmer's idea of using mail coaches in place of the longstanding use of post horses. After initial resistance from the postal authorities, a trial took place in 1784, by which it was demonstrated that a mail coach departing from Bristol at 4pm would regularly arrive in London at 9 o'clock the following morning: a day and a half quicker than the post horses. As a result, the conveyance of letters by mail coach, under armed guard, was approved by Act of Parliament.[26]

Mail coaches were similar in design to the passenger-carrying stage coaches, but were smaller, lighter and more manoeuvrable (being pulled by a team of four horses, rather than six as was usual for a stage coach at that time).[16] The long-established practice of 'riding post' was acknowledged through the provision of four seats inside the coach for passengers. The mail bags were carried in a locked box at the back, above which sat a scarlet-coated guard. While the coaches and coachmen were provided by contractors, the guards worked for the Post Office. As well as two pistols and a blunderbuss, each guard carried a secure timepiece by which departure times at each stage of the journey were strictly regulated.[16]

Rail

In 1830 mail was carried by train for the first time, on the newly-opened Liverpool and Manchester Railway; over the next decade the railways replaced mail coaches as the principal means of conveyance (the last mail coach departed from London on 6 January 1846).[16] The first Travelling Post Office (TPO) was introduced in 1837, and these began to be widely used enabling mail to be sorted in transit;[26] TPO operation was greatly aided by the invention in 1852 of a trackside 'mail-bag apparatus' which enabled bags to be collected and deposited en route. By the 1860s the Post Office had contracts with around thirty different rail companies.

Maritime

The development of marine steam propulsion inevitably affected the packet ship services. Since the 1780s these had been run on behalf of the Post Office by private contractors, who depended on supplementary income from fee-paying passengers in order to make a profit; but in the 19th-century steamships began to lure the passengers away.[16] At some considerable cost the Post Office resolved to build and operate its own fleet of steam vessels, but the service became increasingly inefficient. In 1823 the Admiralty took over managing the long-distance routes out of Falmouth, while services to and from Ireland and the continent were increasingly put out to commercial tender.

Eventually, in 1837, the Admiralty took over control of the whole operation (and with it the remaining Post Office vessels).[16] Subsequently, contracts for carrying mail began to be awarded to new large-scale shipping lines: the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company ran ships out of Southampton to the West Indies and South America, the British and North American Royal Mail Steam-Packet Company (aka the Cunard Line) covered the North Atlantic route, while the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company provided services on eastward routes to the Mediterranean (and onwards to India and eventually Australia). From 1840 vessels carrying mail under Admiralty contract had the privilege of being badged and designated as Royal Mail Ships (RMS). Oversight of the sea mails and packet services reverted from the Admiralty to the Post Office in 1860.[16]

Uniform Penny Postage

In 1840 the Uniform Penny Post was introduced, which incorporated the two key innovations of a uniform postal rate, which cut administrative costs and encouraged use of the system, and adhesive pre-paid stamp. Packets (weighing up to 16 ounces (450 g)) could also be sent by post, the cost of postage varying with the weight.[27] The reforms were devised and overseen by Rowland Hill, having been initially proposed in Parliament by Robert Wallace MP.[5] Hill's proposals, published in a 100-page pamphlet in 1837, were strongly repudiated by the Post Office under its long-standing Secretary Sir Francis Freeling and by the Postmaster General Lord Lichfield, who described them in the House of Lords as being 'of all the wild and visionary schemes [...] the most extraordinary';[16] but among the general public, by contrast, Post Office reform became something of a cause célèbre, with petitions and public meetings attracting large levels of support. With significant public backing, the Penny Postage Bill was introduced to Parliament in July 1839 and passed into law just four weeks later.

By the 1850s the postal system was described as having become 'universal all over the three kingdoms: no village, however insignificant, being without its receiving-house'.[22] In 1855 a network of 920 post offices and 9,578 sub-offices were in place around the country.[16] The 1850s also saw the widespread introduction of red-painted post boxes where the public could deposit their outgoing mail. Few other organisations (either of state or of commerce) could rival the early Victorian Post Office in the extent of its national coverage.[21] Its counters began to be relied upon for providing other government services (e.g. the issuing of licences of various types); and increasingly (and significantly) in this period, the GPO came to be viewed less as a revenue-raising body and more as a public service.[16]

In 1848 Hill, who was an educationalist by background, had introduced a book post service. Pre-stamped postcards, costing one halfpenny (i.e. half the price of a letter) to post, first appeared in 1870. In 1883 Henry Fawcett, whom Gladstone had appointed Postmaster General three years earlier, inaugurated a parcel post service by arrangement with the railway companies;[28] as a result the term 'postman' replaced 'letter-carrier' in the GPO's official nomenclature from October of that year.[29]

Uniform Penny Postage only covered delivery to (and within) a recognised post town; by 1864 this accounted for around 95% of letters posted. Onward delivery of mail to rural addresses, however, continued to incur an additional fee until the GPO's 'Jubilee concession' of 1897, by which it undertook to guarantee delivery to every house in the kingdom at a standard rate.[16]

International postage rates had been standardised to some extent through the establishment of the General Postal Union in 1874; however, the application of additional transit charges by the GPO meant that correspondence within the British Empire subsequently cost more than the 2½d rate for sending letters within the Union. Campaigns for a 'universal penny post', or global flat rate, were spearheaded in the UK by John Henniker Heaton MP; his vision was achieved in part with the (subsidised) introduction of an imperial penny post in 1897.[16]

Financial services

The Money Order Office

In 1838 the Money Order Office was established, to provide a secure means of transferring money to people in different parts of the country (or world), and to discourage people from sending cash by post.[30] The money order system had first been introduced as a private enterprise by three Post Office clerks in 1792, with the permission of the Postmaster General.

Alongside money orders, postal orders were introduced in 1881 (on the initiative of Henry Fawcett and George Chetwynd), which were cheaper and easier to cash.[31] The Money Order Office, however, declined to administer them (it was not until 1904 that the Postal Order Branch and the Money Order Department were finally united);[32] instead, Chetwynd himself (in his role as Receiver and Accountant-General of the Post Office) took responsibility.

Postal orders and money orders were vital at this time for transactions between small businesses, as well as individuals, because bank transfer facilities were only available to major businesses and for larger sums of money.[25]

The Post Office Savings Bank

The Post Office Savings Bank (POSB) was inaugurated in 1861, when there were few banks outside major towns; George Chetwynd and Frank Ives Scudamore were its key proponents. Two years later, 2,500 post offices were offering a savings service. Henry Fawcett in the 1880s greatly expanded its operations and encouraged the use of savings stamps; by the end of the century the number of POSB branches had increased to 14,000, making it the largest banking system in the country.[16]

Other services

Gradually more financial services were offered by post offices, including government stocks and bonds in 1880, insurance and annuities in 1888, and war savings certificates in 1916. In 1909 old age pensions were introduced, payable at post offices.[33] In 1956 a lottery bond called the Premium Bond was introduced. In the mid-1960s the GPO was asked by the government to expand into banking services which resulted in the creation of the National Giro in 1968.[33]

New communication systems

When new forms of communication came into existence in the 19th and early 20th centuries the GPO claimed monopoly rights on the basis that like the postal service they involved delivery from a sender and to a receiver. The theory was used to expand state control of the mail service into every form of electronic communication possible on the basis that every sender used some form of distribution service. These distribution services were considered in law as forms of electronic post offices. This applied to telegraph and telephone switching stations.

Telegraph

In 1846, the Electric Telegraph Company, the world's first public telegraph company, was established in the UK and developed a nationwide communications network. Several other private telegraph companies soon followed. The Telegraph Act 1868 granted the Postmaster General the right to acquire inland telegraph companies in the United Kingdom and the Telegraph Act 1869 conferred on the Postmaster General a monopoly in telegraphic communication in the UK. The responsibility for the 'electric telegraphs' was officially transferred to the GPO in 1870. Overseas telegraphs did not fall within the monopoly. The private telegraph companies that already existed were bought out. The new combined telegraph service had 1,058 telegraph offices in towns and cities and 1,874 offices at railway stations. 6,830,812 telegrams were transmitted in 1869 producing revenue of £550,000.[34] The fledgling department was overseen by Frank Scudamore (who had devised and carried out the plan for nationalisation), but he resigned in 1875 after he was found to have diverted money from the Savings Bank and elsewhere in a vain attempt to mitigate the fast-rising costs of the expanding operation.[16]

London's Central Office in the first decade of nationalized telegraphy created two levels of service. High-status circuits catering to the state, international trade, sporting life, and imperial business. Low-status circuits directed toward the local and the provincial. These distinct telegraphic orbits were connected to different types of telegraph instruments operated by differently gendered telegraphists.[35]

1909 saw the establishment of the Research Section of the Telegraph Office, which had its origins in innovative areas of work being pursued by staff in the Engineering Department.[36] In the 1920s a dedicated research station was set up by the GPO seven miles away in Dollis Hill; during the Second World War the world's first electronic computer, 'Colossus', was designed and constructed there by Tommy Flowers and other GPO engineers.[37]

The Telegraph Office was slightly damaged by a German bomb in 1917 and in 1940, was set alight during the London Blitz, destroying much of the interior. It reopened in 1943. By the 1950s, the volume of telegraph traffic had declined and the Telegraph Office closed in 1963. In 1984 the new British Telecom Centre was opened on the site.[38]

Telephone

The Post Office commenced its telephone business in 1878, however the vast majority of telephones were initially connected to independently run networks. In December 1880, the Postmaster General obtained a court judgement that telephone conversations were, technically, within the remit of the Telegraph Act. The General Post Office then licensed all existing telephone networks.

The effective nationalisation of the UK telecommunications industry occurred in 1912 with the takeover of the National Telephone Company which left only a few municipal undertakings independent of the GPO (in particular the Hull Telephones Department (now privatised) and the telephone system of Guernsey). The GPO took over the company on 1 January 1912; transferring 1,565 exchanges and 9,000 employees at a cost of £12,515,264.

The GPO installed several automatic telephone exchanges from several vendors in trials at Darlington on 10 October 1914 and Dudley on 9 September 1916 (rotary system), Fleetwood (relay exchange from Sweden), Grimsby (Siemens), Hereford (Lorimer) and Leeds (Strowger).[39] The GPO then selected the Strowger system for small and medium cities and towns.

The telephone systems of Jersey and the Isle of Man, obtained from the NTC were offered for sale to the respective governments of the islands. Both initially refused, but the States of Jersey did eventually take control of their island's telephones in 1923.

Radio

On 27 July 1896, Guglielmo Marconi gave the first demonstration of wireless telegraphy from the roof of the Telegraph Office in St. Martin's Le Grand.

The development of radio links for sending telegraphs led to the Wireless Telegraphy Act 1904, which granted control of radio waves to the General Post Office, who licensed all senders and receivers. This placed the Post Office in a position of control over radio and television broadcasting as those technologies were developed.

An expanded workforce

Around fifty women were working as operators for the telegraph companies when they were acquired by the Post Office in 1869; this prompted a change of policy to enable and encourage the recruitment of women to a number of other roles in the organisation (for example, by the end of the following decade half of all counter clerks in London were women).[16] The GPO provided a number of benefits for its workers (including, from the 1850s, free medical care and a non-contributory pension scheme), however only so-called 'establishment' workers were included: around 40% of the workforce was deemed to be 'non-establishment', including the telegraph boys (who were generally aged 14-16), most female employees and the many part-time 'auxiliaries' who filled a variety of roles; all these were paid at a reduced rate with far fewer benefits.

The importance of workers' rights began to be addressed by Henry Fawcett in the 1880s,[notes 5] who established a scheme for improved pay and conditions for telegraphy workers and sorting clerks.[16] During his tenure the first permanent postal workers' union was formed (the Postal Telegraph Clerks' Association) in 1881; others followed, including the United Kingdom Postal Clerks' Association (1887), the Fawcett Association (1890) and the Postmen's Federation (1891); (by 1919 these and other groupings would merge together to form the Union of Post Office Workers).

The GPO in the twentieth century

By 1900 house-to-house mail delivery was taking place across England (and was close to being in place in Scotland and Ireland).[5] That year there were nearly 22,000 post offices operating across the United Kingdom: 906 were classified as Head Post Offices (HPOs); these functioned as the head office for their locality and included sorting facilities as well as a counter service. Under the HPOs were a further 255 associated branch offices, in addition to which there were 4,964 town sub-offices and 15,815 country post offices (which were run by sub-postmasters and mistresses, who were self-employed and paid on commission, unlike the larger 'Crown' offices where the counter staff were all GPO employees).[21]

On the eve of the First World War, in 1914, the Post Office is said to have been 'the biggest economic enterprise in Britain and the largest single employer of labour in the world', employing over 250,000 people and with an annual revenue of £32 million.[40] The GPO ran the nation's telegraph and telephone systems, as well as handling some 5.9 billion items of mail each year, while branch post offices offered an increasing number of financial, municipal and other public services alongside those relating to postage.[40]

By the 1920s, motor vehicles had begun to replace the (previously ubiquitous) horse and cart on short-haul postal routes; later that same decade the use of postal counties was introduced to help make the sorting process for deliveries more efficient.[16]

Ireland

In 1831, the office of Postmaster General of Ireland had been amalgamated with the equivalent office for Great Britain; for the next 90 years the GPO operated throughout Great Britain and Ireland. In 1916, during World War I, the General Post Office, Dublin was a focus of the Easter Rising, during which the GPO served as the headquarters of the uprising's leaders. It was from outside this building on the 24th of April 1916, that Patrick Pearse read out the Proclamation of the Irish Republic.[41] (The building was destroyed by fire in the course of the rebellion, save for the granite facade, and not rebuilt until 1929, by the Irish Free State government).

Following the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921, responsibility for posts and telegraphs in most of Ireland (but not in Northern Ireland) transferred to the new Provisional Government and then, upon the formal establishment of the Irish Free State in December 1922, to the Free State Government. A Postmaster General was initially appointed by the Free State Government, being replaced by the office of Minister for Posts and Telegraphs in 1924. An early visible manifestation was the repainting of all post boxes in the new Free State in green instead of red. In 1984, the Department of Posts and Telegraphs ('the P. & T.') was replaced by the separate Irish state-owned companies An Post and Telecom Éireann.

Control of broadcasting

In 1922 a group of radio manufacturers formed the British Broadcasting Company (BBC), which was the sole organisation granted a broadcasting licence by the GPO. In 1927, the original BBC was dissolved and reformed by royal charter as the British Broadcasting Corporation.

From the start the GPO had trouble with competitive pirate radio broadcasters who found ways to deliver electronic messages to British receivers without first obtaining a GPO licence. These competitors were well aware of the fact that the GPO would never grant them such a licence. To police these unlicensed stations the GPO evolved its own force of detectives and "detector vans".

The radio regulation functions were transferred to the Independent Broadcasting Authority and later Ofcom. Due to its regulatory role, as well as its expertise in developing long-distance communication networks, the GPO was contracted by the BBC, and the ITA in the 1950s and 60s, to develop and extend their television networks. A network of transmitters was built, connected at first by cable, and later by microwave radio links. The Post Office also took responsibility for the issuing of television licence fees (and radio, until 1971), and the prosecution of evaders until 1991.

Growth in telecommunications

The GPO wished to standardise on the Strowger switch (also called SXS or step-by step) but the basic SXS exchange was not suitable for a large city like London until the Director telephone system was developed by the Automatic Telephone Manufacturing Company in the 1920s. The first London Director exchange, HOLborn, cutover on Saturday 12 November 1927, BIShopgate and SLOane exchanges were to follow in six weeks, followed by WEStern and MONument exchanges. The London area contained 80 exchanges, and full conversion would take many years.[42]

All London customers were given seven-digit numbers, with the first three digits spelling out the (local) exchange name. In March 1966 after all London (and other Director) exchanges were automatic, all-figure dialling was introduced. The Director system enabled the London network to operate with both automatic and manual exchanges in the local network until the 1960s and it was subsequently installed in other large British cities; starting with Manchester (1930), then Birmingham (1931), Glasgow (1937), Liverpool (1941), and Edinburgh (1950).[43]

After the Second World War, there began to be an unprecedented demand for telephone services. In addition, there was the need to make comprehensive repairs, and upgrades to a network which had been severely degraded by war, and lack of investment. Waiting lists for new telephone lines quickly emerged, and persisted for several decades. To alleviate the situation, the Post Office began to provide shared service residential lines, each known as a party line, which could share a cable pair. Most of the line was shared between two subscribers usually splitting off to each within sight of the houses, and both lines attracted a small discount; however, this arrangement had its disadvantages.

At this time, the majority of lines in rural, and regional areas (particularly in Scotland and Wales) were still manually switched. This inhibited growth, and caused bottlenecks in the network, as well as being labour and cost-intensive. The Post Office began to introduce automatic switching, and replaced all of its 6,000 exchanges. Subscriber Trunk Dialling (STD) was also added from 1958, which allowed subscribers to dial their own long-distance calls.

Telecommunications services in the United Kingdom were reorganised as Post Office Telecommunications in October 1969; and then as British Telecom in 1980, although remaining part of the GPO until 1981.

1930s reviews and innovations

The Bridgeman Committee, chaired by Lord Bridgeman, was set up in 1932 to investigate criticisms of the General Post Office and reported the same year.[44] It highlighted defects in the structure of the organisation and recommended creation of a new Board (to be chaired by the Postmaster-General) and a new official: the Director-General, who would serve as vice-chair 'with the duty of ensuring that board decisions were made effective and that continuity and unity of policy were maintained'.[45]

The Motor Transport branch was established in 1932; previously provision of motor vehicles had been contracted out, but henceforward the GPO would maintain its own fleet, the mainstays of which were, initially, Morris Minor vans (built to the Post Office's own specification) and BSA motorcycles (which were used by the telegraph boys).[16]

In 1933 Sir Stephen Tallents was appointed to head up a new public relations department.[46] Among other things he established the influential GPO Film Unit, while his acumen in the field of graphic design led to the Post Office becoming a leader and trend setter in its use of posters for the purposes of marketing, information and publicity.[47]

The number of airmail flights on offer had multiplied during the 1920s, with government-supported long-haul services provided initially by the RAF and then by Imperial Airways; but the GPO's role in these enterprises was minimal (beyond providing blue air mail labels at counters and directing labelled mail to Croydon Aerodrome).[16] In 1935, however, the pioneering Postmaster-General Kingsley Wood sanctioned an Empire Air Mail Scheme, by which a half-ounce letter could be sent anywhere in the Empire for a flat rate of three-halfpence (1½ d);[notes 6] the scheme was rolled out in stages from 1937-38. Whilst immediately successful, it proved costly both to Imperial Airways (who had drastically underestimated the volume of cargo it would have to carry)[notes 7] and the Post Office (who had agreed to subsidise the company through tonnage payments). Airmail services ceased with the outbreak of war in 1939.[16]

The Gardiner Committee, chaired by Sir Thomas Gardiner, was set up to investigate improvements in efficiency and reported in 1936. The report recommended the setting up of eight provincial regions outside London,[notes 8] and the introduction of the London Postal Region and London Telecommunications Region for the capital and surrounding area. The changes were implemented between 1936 and 1940.

During World War II the generation of engineers trained by the GPO for its telecommunications operations were to have important roles in the British development of radar and in code breaking. The Colossus computers used by Bletchley Park were designed and built by GPO engineer Tommy Flowers and his team at the Post Office Research Station in Dollis Hill.

Dissolution

Under the Post Office Act 1969, the assets of the GPO were transferred from a government department with a royal charter to a statutory corporation named the Post Office (the word 'General' being dropped from the name). Responsibility for telecommunications was given to Post Office Telecommunications, the successor of the GPO Telegraph and Telephones department, with its own separate budget and management.

Jersey Post and Guernsey Post became independent in 1969, followed by Guernsey and Jersey Telecom in 1973. Isle of Man Post also commenced operation on 5 July 1973.

In 1969, the Post Office Savings Bank was transferred to the Treasury, and renamed the National Savings Bank.[49]

The British Telecommunications Act 1981 split off the telecommunications business to form the British Telecommunications corporation, leaving the Post Office corporation with the Royal Mail, parcels, Post Office Counters and National Giro businesses. British Telecommunications was converted to British Telecommunications plc in 1984, and was privatised. Girobank was divested to Alliance & Leicester in 1990.

As part of the Postal Services Act 2000, the businesses of the Post Office were transferred in 2001 to a public limited company, Consignia plc, which was quickly renamed Royal Mail Holdings plc. The government became the sole shareholder in Royal Mail Holdings plc and its subsidiary Post Office Ltd.

Finally, on 5 April 2007, the government published The Dissolution of the Post Office Order 2007 under which the old Post Office statutory corporation was formally abolished, with effect from 1 May 2007.

Post Office Headquarters

The head office of the General Post Office was firmly established in the City of London by 1653, in a sizeable building at the lower end of Threadneedle Street (by the junction with Poultry, Cornhill and Lombard Street).[50] Prior to this date there is evidence of the posts having been administered at various times either from the house of the chief postmaster or from one of the City's post houses. The office in Threadneedle Street was destroyed in the Great Fire of London, after which various temporary locations were used up until 1678, when a new office was established in Lombard Street.[50] The General Post Office remained there for the next 150 years.

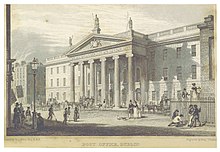

St Martin's Le Grand

Having outgrown its premises in Lombard Street, the General Post Office purchased slums on the east side of St. Martin's Le Grand and cleared them to establish a new headquarters, Britain's first purpose-built mail facility. The new General Post Office building, designed with Grecian ionic porticoes by Sir Robert Smirke, was built between 1825 and 1829, ran 400 feet (120 m) long and 80 feet (24 m) deep, and was lit with a thousand gas burners at night.[51] Afterwards 'St. Martin's Le Grand' began to be used as a metonym for the General Post Office (a usage which continued well into the 20th century).[28]

In the 1840s there were, in addition to the chief office at St. Martin's Le Grand, four branch offices in London: one in the City at Lombard Street (in part of the old headquarters building); two in the West End at Charing Cross and Old Cavendish Street near Oxford Street; and one south of the Thames in Borough High Street.[52]

In 1874, a new headquarters building ('GPO West') was opened on the western side of the street, containing a suite of public rooms and offices for the Postmaster General, the senior officials and all their administrative staff. This left Smirke's building ('GPO East') to function mainly as a sorting office. The upper floors of the new building housed the GPO's newly-acquired telegraph department; but as this fast expanded, more space was needed and in the 1890s a separate new headquarters building was opened ('GPO North'), immediately to the north of the telegraph building. This remained the headquarters of the GPO, and then of the Post Office, until 1984.[53]

In the early 20th century various different departments of the General Post Office (most of which had begun their days in St Martin's Le Grand) were provided with their own headquarters in different parts of London: the Post Office Savings Bank was in Blythe House, West Kensington; the Postal and Money Order office in Manor Gardens, off Holloway Road; the Stores Department was in Studd Street, Islington and the Telephone Department in Queen Victoria Street (in what became the Faraday Building).[28] In 1910 the King Edward Building was opened on King Edward Street (immediately to the west of GPO North) to serve as the new 'London Chief Office' in place of Smirke's GPO East; the latter was then demolished two years later.

Links to the intelligence services

The practice of intercepting letters for intelligence purposes was well-established by the Commonwealth period, and it continued after the Restoration. In the early 18th century the authority of Ministers of the Crown to open and read letters for reasons of public safety had been clearly established by statute, drawn up by Lord Somers. Warrants were frequently applied for in the 18th-century, sometimes on trivial premises, and by the 1730s a permanent office had been established, in which a number of cryptanalysts were employed (as 'His Majesty's Post-Office decipherers'), among them the Revd Dr Edward Willes.

In 1844 it was revealed in the House of Commons, in response to an enquiry by Thomas Slingsby Duncombe, that the Home Office had issued a warrant for the Post Office to intercept and investigate correspondence pertaining to Giuseppe Mazzini. The Home Secretary, Sir James Graham, admitted the interception but did not divulge the reason for it.[11] Duncombe contended that warrants for intercepting mail were being issued at the request of foreign governments, in a way that was both unconstitutional and unlawful. The accusations prompted widespread expressions of disapproval and further questions in Parliament. In response to public disquiet, a select committee was set up 'to inquire into a department of Her Majesty's Post-Office commonly called "the secret or inner office", the duties and employment of the persons engaged therein, and the authority under which the functions of the said office were discharged'.[11]

The Mazzini affair left the Post Office wary of involvement in espionage, and legislation was put in place to prevent letters from being opened without a warrant.[16] In 1910, however, the Home Secretary (Winston Churchill) issued a 'general warrant' allowing the Secret Service Bureau to intercept letters at will; in the run-up to the First World War individuals who had been placed under surveillance routinely had their mail monitored. During the Second World War, and for some years after, a department called the GPO Special Investigations Unit was responsible for intercepting letters as part of British intelligence service operations. The unit had branches in every major sorting office in the UK and in St Martin's Le Grand GPO, near St Paul's Cathedral. Letters targeted for interception by the Special Investigations Unit were steamed open and the contents photographed, and the photographs were then sent in unmarked green vans to MI5.[54]

Post Office Rifles

In 1868, as part of the Volunteer Movement, John Lowther du Plat Taylor, Private Secretary to the Postmaster General, raised the 49th Middlesex Rifle Volunteers Corps (Post Office Rifles) from GPO employees, who had been either members of the 21st Middlesex Rifles Volunteer Corps (Civil Service Rifles) or special constables enrolled to combat against Fenian attacks on London in 1867/68.[55]

The regiment was restyled 24th Middlesex Rifle Volunteers Corps (Post Office Rifles) in 1880 as part of the Cardwell Reforms.

‘M' Company, 24th Middlesex Rifle Volunteers Corps, was formed by royal warrant in 1882 as the Army Post Office Corps (APOC). This newly formed Army Reservist company saw active service providing a postal service to the British military expeditions to Egypt (1882), Suakin (1885) and the Anglo Boer War (1899–1902).[56] The APOC was eventually subsumed by the Royal Engineers in 1913 to re-emerge as the Royal Engineers (Postal Section) Special Reserve. The Postal Section provided the Army Postal Service (now British Forces Post Office) in the First and Second World Wars and in 1993 became the Postal & Courier Service Royal Logistic Corps.

In the second week of December 1869 the War Office declared that 22nd Company RE, commanded by Capt Charles Edmund Webber RE, was to be seconded to the GPO on telegraph duties. The first draft took up their appointments with the GPO in June 1870; Webber as South East District divisional engineer based in New Cross, London, his subalterns as district superintendents of the divisional engineer and the NCOs and sappers as inspectors and linesmen/signallers respectively. They received training at both the School of Military Engineering and the London School of Telegraphy and were for a time billeted at St John’s Woods Barracks, London. The following year the Chatham based 34th Company RE joined 22nd at the GPO. It deployed detachments to GPO offices in Inverness, Ipswich and Bristol. The Company HQ was principally based in Ipswich, but later moved to Bristol. The two companies operated the telegraph services in their respective districts. Exploiting the ‘wayleave’ agreements, struck for the laying of rail tracks forty years earlier, they further developed the national telegraph network by laying new lines to the more remote parts of the British Isles [55]

In 1883 the regiment raised 'L’ Company as a Telegraph Corps, a year later it was redesignated as the Telegraph Reserve Royal Engineers. Its role was to supplement the Regular Army's telegraph services operated by the Royal Engineers.[55]

After the Haldane Reforms the regiment kept its association with the Post Office and continued to recruit postal workers into the Territorial Force under its new title '8th (City of London) Battalion, The London Regiment (Post Office Rifles)' in 1908. It served as an infantry regiment in the First World War (1914–18). Sergeant Alfred Joseph Knight was awarded the Victoria Cross for his bravery in the Capture of Wurst Farm (20 September 1917). The regiment was disbanded in 1921.

Lists of senior officials

The Postmaster General was the government minister in charge of the GPO (the office was held jointly by two appointees between 1691 and 1823). The Secretary of the Post Office was the senior civil servant (equivalent to a permanent secretary), who managed the operation from day to day. Evelyn Murray, who served as Secretary until 1934, was not replaced when he left office. Instead a Director-General was appointed, together with a Board which brought together a number of GPO heads of department.[16]

Postmasters General

Secretaries of the Post Office

| Name | Date of appointment |

|---|---|

| John Avent | 20 June 1694 |

| Benjamin Waterhouse | c.1700 |

| Henry Weston | c.1714 |

| Joseph Godman | c.1720 |

| W. Rouse | c.1730 |

| Thomas Robinson | c.1737 |

| John D. Barbutt | 15 September 1739 |

| George Shelvocke | 22 July 1742 |

| Henry Potts | 19 March 1760 |

| Anthony Todd | 1 December 1762 |

| Henry Potts | 19 July 1765 |

| Anthony Todd | 6 January 1768 |

| Francis Freeling | 7 June 1798 |

| William Leader Maberly | 29 September 1836 |

| Rowland Hill | 22 April 1854[notes 9] |

| John Tilley | 15 March 1864 |

| Stevenson Arthur Blackwood | 1 May 1880 |

| Spencer Walpole | 10 November 1893 |

| George H. Murray | 10 February 1899 |

| Henry Babington Smith | 1 October 1903 |

| Matthew Nathan | 17 January 1910 |

| Alexander F. King | 1 October 1911 |

| Evelyn Murray | 24 August 1914 |

Directors General of the Post Office

| Name | Date of appointment |

|---|---|

| Donald Banks | 14 April 1934 |

| Thomas Gardiner | 9 August 1936 |

| Raymond Birchall | 1 January 1946 |

| Alexander Little | 1 October 1949 |

| Gordon Radley | 1 October 1955 |

| Ronald German | 1 June 1960 |

Sir Ronald German was replaced by John Wall on 1 November 1966, who had been brought in from the private sector to serve as 'Deputy Chairman of the Board' in preparation for the GPO's disestablishment. He departed in September 1968, after which it was announced that the Postmaster General, John Stonehouse, would assume the role of 'Chairman and Chief Executive' in preparation for the business's re-establishment as a public corporation the following year.[16]

See also

- GPO Film Unit

- GPO telephones

- Post Office Research Station

- Postal, telegraph and telephone service

- Postmaster General of the United Kingdom

- Red telephone box

- Royal Mail

- Television licensing in the UK

Notes

- ^ The original meaning of 'post' in this context comes from the horses being placed or 'posted' (Latin positi) at regular intervals along the route.

- ^ As per the 1657 Act, a single-sheet letter cost 2d up to 80 miles, 3d over 80 miles and 4d for carriage to or from Scotland.

- ^ Ireland at about this time had three post roads (the Connaught road, the Munster road and the Ulster road) likewise staffed by Deputy Post-Masters (45 in number).

- ^ The term 'bye-posts' also covered 'letters not going or coming from, to or through London'.

- ^ Fawcett, as well as being Postmaster General, was Professor of Political Economy at Cambridge and a noted political Radical; his wife Millicent was a leading suffragist.

- ^ The cost was the same as for letters sent by sea, except that the sea rate allowed letters weighing up to an ounce.

- ^ Between 1935/6 and 1938/9, the number of letters sent annually by airmail increased from 10.8 million to 91.2 million.

- ^ Home Counties; Midland; Northern Ireland; North-Eastern; North-Western; Wales and Border Counties; Scotland; South-Western

- ^ Between 1846 and 1854 Hill had served in the distinct role of Secretary to the Postmaster General (a position created specifically for him).

References

- ^ "Summary of Post Office history". The British Postal Museum & Archive. Archived from the original on 17 May 2011.

- ^ Marshall, Allan (2003). Intelligence and Espionage in the Reign of Charles II, 1660–1685. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780521521277.

- ^ "About us". Royal Mail. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ "NM04 notice for Royal Mail plc". 3 October 2022. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Hemmeon, J. C. (1912). The History of the British Post Office. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard university. pp. 13–34. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ a b Borer, Mary Cathcart (1972). The British Hotel through the Ages (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Lutterworth Press. pp. 44–45.

- ^ a b "Post Office". Encyclopaedia Britannica (vol. XVIII) (7th ed.). Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black. 1842. pp. 486–497.

- ^ Beale, Philip (1998). A History of the Post in England from the Romans to the Stuarts (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. p. 154.

- ^ May, Steven W. (2023). English Renaissance Manuscript Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 144.

- ^ Hume, David; Stafford, William Cooke (1867). History of England from the Earliest Time to the Present Day (Vol. II). London: London Printing and Publishing Co. Ltd. p. 311.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lewins, William (1864). Her Majesty's Mails: an Historical and Descriptive Account of the British Post-office. London: Sampson Low, Son, and Marston. pp. 1–18.

- ^ a b "A PROCLAMATION for the settling of the Letter-office of England and Scotland". Report from the Secret Committee on the Post-Office; together with the Appendix. London: House of Commons. 1844. p. 57.

- ^ "The Secret Room". The British Postal Museum & Archive. 2011. Archived from the original on 31 August 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- ^ "Royal Mail loses postal monopoly". BBC News. 18 February 2005. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ "Charles II, 1660: An Act for Erecting and Establishing a Post Office. | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Campbell-Smith, Duncan (2011). Masters of the Post: The Authorized History of the Royal Mail. London: Penguin Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g Joyce, Herbert (1893). The History of the Post Office from Its Establishment Down to 1836. London: Richard Bentley & Son.

- ^ a b Blome, Richard (1673). Britannia: or, a Geographical Description of the Kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland, with the Isles and Territories thereto belonging. London: Thomas Roycroft. pp. 12–15.

- ^ Daybell, James (2012). The Material Letter in Early Modern England: Manuscript Letters and the Culture and Practices of Letter-Writing, 1512-1635. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 136.

- ^ "Post Office Blue Ensign (before 1864)". Royal Museums Greenwich. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d Stray, Julian (2010). Post Offices. Botley, Oxon.: Shire Publications Ltd.

- ^ a b "Metropolitan Post-Offices. The Chief Office, London". The Illustrated Magazine of Art. 1 (6): 327–32. 1853. JSTOR 20537996. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ "Public Offices, Ninth Report: General Post Office". Reports from Commissioners (Ireland). X: 3. 23 January – 21 June 1810.

- ^ Tombs, Robert Charles (1905). The King's Post. Bristol: W. C. Hemmons. p. 21.

- ^ a b Joyce, Patrick (2013). "Postal economy and society". The State of Freedom: A Social History of the British State since 1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 114–115.

- ^ a b Account of the Celebration of the Jubilee of Uniform Inland Penny Postage. London: General Post Office. 1891. pp. 15–18.

- ^ Dickens, Charles (September 1850). "Mechanism of the Post Office". The Eclectic Magazine: 74–95.

- ^ a b c Muirhead, Findlay, ed. (1922). The Blue Guides: London and its Environs (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan and Co. Ltd. pp. 225–226.

- ^ "Historical Post Office roles". The Postal Museum. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ Callender, Henry (1868). The Post-Office and its Money Order System. Edinburgh: Edmondston and Douglas. pp. 6–8.

- ^ "140 Years of Postal Orders". Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ Fiftieth Report of the Postmaster General on the Post Office (PDF). London: HMSO. 1904. p. 26. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ a b "Post Offices – Securing their Future: Annex A – The development of the post office network". UK Parliament. 23 June 2009. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- ^ Tom Standage, The Victorian Internet: The remarkable story of the telegraph and the nineteenth century's online pioneers (Phoenix, 1998) online.

- ^ Katie Hindmarch-Watson, "Embodying Telegraphy in Late Victorian London." Information & Culture 55#1 (2020): 10-29 online

- ^ "The Post Office Research Station". Nature. 162 (4106): 51–53. 10 July 1948. Bibcode:1948Natur.162...51.. doi:10.1038/162051a0.

- ^ "Colossus". The National Museum of Computing. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ "Central Telegraph Office and BT Centre – a timeline" (PDF). www.bt.com. BT Archives. May 2008. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ Events in Telecommunications History - 1927 Archived 22 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine BT Archives

- ^ a b "The Post Office in 1914". The Postal Museum. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ "Easter Rising – Day 1: Rebels on the streets". The Irish Times. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ The Times (London), 1927; 14 November p 9, 16 November p 9

- ^ "UK TELEPHONE HISTORY". www.britishtelephones.com.

- ^ "Events in Telecommunications History: 1932". BT Archives. British Telecom. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ^ "Report on the Post Office". Nature. 130 (3279): 338–339. 3 September 1932. Bibcode:1932Natur.130R.338.. doi:10.1038/130338b0. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ "GPO Film Unit (1933-1940)". Screenonline. British Film Institute. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ "Posters". The Postal Museum. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Heritage". Post Office Vehicle Club. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ Story of NS&I Archived 17 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine National Savings & Investments, 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2013. Archived here.

- ^ a b Greenwood, Jeremy (August 1973). "The Location of the London Head Office and Post Houses 1526-1687" (PDF). London Postal History Group Notebook (13): 3–5.

- ^ "The General Post Office East: 1829–1912". Postal Heritage. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- ^ "Victorian London – Communications – Post – General Post Office". The Dictionary of Victorian London. Lee Jackson.

- ^ Weinreb, Ben; Hibbert, Christopher, eds. (1993). "Post Office". The London Encyclopaedia (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. p. 634.

- ^ Saunders, Frances Stonor (9 April 2015). "Stuck on the Flypaper". London Review of Books. 37 (7): 3. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ a b c SC Fenwick (2014). Rifle Volunteers and Distance Writing – Why the Posties became Sappers. 128. Royal Engineers Journal

- ^ Col ET Vallance (2015). Postmen at War – A history of the Army Postal Services from the Middle Ages to 1945. Stuart Rossiter Trust, Hitchin. p. 46

Further reading

- Bruton, Elizabeth. "Something in the air: The Post Office and early wireless, 1882–1899." in Knowledge Management and Intellectual Property (Edward Elgar, 2013).

- Campbell-Smith, Duncan. Masters of the Post: The Authorized History of the Royal Mail (Penguin 2012)

- Clinton, Allan. Post Office Workers: A Trade Union and Social History (George Allen and Unwin, 1984)

- Daunton, M. J. Royal Mail: The Post Office Since 1840 (Athlone, 1985).

- Hemmeon, Joseph Clarence. The history of the British post office (Harvard University Press, 1912) online.

- Hochfelder, David. "A comparison of the postal telegraph movement in Great Britain and the United States, 1866–1900." Enterprise & Society 1.4 (2000): 739–761.

- Lin, Chih-lung. "The British dynamic mail contract on the North Atlantic: 1860–1900." Business History 54.5 (2012): 783–797.

- Morus, Iwan Rhys “‘The Nervous System Of Britain’: Space, Time, and the Electric Telegraph in the Victorian Age,” British Journal for the History of Science 33#4 (2000): 455–75, online

- Perry, C. R. The Victorian Post Office: The Growth of a Bureaucracy (Boydell Press, 1992)

- Standage, Tom. The Victorian Internet: The remarkable story of the telegraph and the nineteenth century's online pioneers (Phoenix, 1998) online

External links

- The British Postal Museum & Archive

- An 18th-century listing of expenses, shipping schedules, and regulations for the office on Lombard Street

- BT Archives

- Connected Earth (History of Communications) Archived 10 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Bath Postal Museum

- Royal Mail Group – About us

- Site for former Leicestershire Telegram Messenger Boys

- G.P.O. GLASGOW (c.1961) (archive film showing functions of the telephone exchange, enquiries and repair – from the National Library of Scotland: SCOTTISH SCREEN ARCHIVE)

Log in to post an annotation.

If you don't have an account, then register here.

References

Chart showing the number of references in each month of the diary’s entries.

1666

- Nov

16 Annotations

First Reading

CGS • Link

see: http://www.pepysdiary.com/encyclo…

CGS • Link

OED

1. (Usu. with capital initials.) The public department or corporation responsible for the collection, transmission, and distribution of letters, parcels, etc., by post, and, in later use, for other services, such as (in some countries) telecommunications.

Formerly also: the office of the master of the posts, or postmaster general (obs.).

In many instances it is difficult to separate this sense from the local branch or the headquarters of the department: see sense 2.

1652 Orig. Jrnls. House of Commons 19 Oct. XXXVII. 124 Mr Benjamin Moore, and Mr Wm Jessops claime to the fforeigne post office. 1657 in H. Scobell Acts & Ordin. Parl. (1658) c. 30. 512 From henceforth there be one General Office, to be called and known by the name of the Post-Office of England; and one Officer..nominated and appointed..under the Name and Stile of Postmaster-General of England, and Comptroller of the Post-Office.

Second Reading

San Diego Sarah • Link

In 1663 Barbara Villiers Palmer, Countess of Castlemaine used her house as a rendezvous for those at court who disliked Chancellor Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon (think of the recent Earl of Bristol entries). Her annual income consisted of 4,700 pounds a year from the Post Office, and amounts taken from customs and excise. She also took money from people seeking to advance at court and in offices. Even the French and Italian ambassadors sought her influence with Charles II. Notes from: http://scandalouswoman.blogspot.c…...

Postmaster General Daniel O'Neil used codes to give information to James Butler, Duke of Ormond, on Castlemaine's behavior and the financial mismanagement of the country.

San Diego Sarah • Link

Read more at http://www.nottinghampost.com/byg…

Henry VIII came up with the idea of a postal service. He wanted a network of routes radiating from London along which letters of court could be carried by messengers. At various points, fresh horses would be ready to keep the messengers on the move. England had its Royal Mail.

Charles II expanded the Royal Mail to allow the routes to be used by everyone. Staging points evolved into post offices where letters were charged.

Nottingham got its postmaster in 1621. Richard Bullyvant was paid 25 shillings, 7 pence "for his pains in ridinge to Newark, Derby ..."

By 1637, there was a fortnightly delivery of mail from Nottingham to London – by foot! The brave postman had to trek more than 100 miles with the ever-present peril of highwaymen en route.

Because of Newark's position on the main London to York coach route, it held the honor of being head post office in Nottinghamshire, but once mail coaches began to run between Nottingham and the capital in 1784, Newark's importance waned.

Bouncing along the rutted tracks of old England, the coach journey took 24 hours with the Blackamoor's Head at the corner of Nottingham High Street and Pelham Street one of the most important coaching hostels.

Seedsman John Raynor established the first Nottingham post office in his shop on High Street, helped by Thomas Crofts, of Greyfriar Gate, who would tour the town ringing his bell – now on display in the British Postal Museum – accepting and delivering letters, and collecting the postage.

Business boomed, and over the next few decades new coaching routes opened. It became a competitive affair with coach drivers urging their steeds to average speeds of 10 miles an hour. The horses ran for an hour a day, three days a week, and had a career on the first-class service of about four years.

There were also changes in Nottingham, Raynor's post office moving to larger premises in High Street Place and then to Bridlesmith Gate.

In 1831, cast iron plates bearing street names were erected in Nottingham and within a year, demands to make life easier for postmen by numbering properties were first heard.

In 1840 the penny postage scheme, regardless of distance, became law and for the first time, the public could buy the famous Penny Black stamps. People flocked to Bridlesmith Gate where postmaster John Crosby and his staff were "off their heads with work and worry", trying to meet demand.

Envelopes weren't invented until the 1870s – a single sheet of paper sufficed, folded in two and sealed with wax.

San Diego Sarah • Link

For a comprehensive description of the development of the Post Office I found a free book on line:

THE HISTORY OF THE BRITISH POST OFFICE by J. C. HEMMEON, Ph.D., published by CAMBRIDGE HARVARD UNIVERSITY in 1912

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/4…

The first two chapters cover the early years and Pepys' times.

San Diego Sarah • Link

In 1660 many old Royalist claimants to farm the Post Office petitioned Charles II and Parliament for reappointment to their old places and incomes. James Hicks [Hickes], a clerk who had worked directly for King Charles and Thurloe, was asked to investigate how many of the old deputy postmasters were eligible for positions.

Hicks found many of the real claimants were dead, and many of the applicants had been enemies of the King.

Finally, Henry Bishop was appointed by royal patent Postmaster General of England for 7 years at a rent of £21,500 a year.

For the time being Bishop was to charge the same rates as those in the "pretended Act of 1657," to defray all postal expenses and to carry free all public letters and letters of members of Parliament during the present session.

He agreed also to allow the Secretaries of State to examine letters, not to change old routes or set up new without their consent, to dismiss all officials objected to on reasonable grounds. If his income should be lessened by war or plague, or if this grant should prove ineffectual, the Secretaries agreed to allow such abatement in his farm as should seem reasonable to them.1

1 Rep. Com., 1844, xiv, app., pp. 75, 76 (32, 53).

Bishop's regime was unpopular with the postmasters, and 300 of them (representing themselves to be "all the postmasters in England, Scotland, and Ireland") petitioned Parliament to protest his actions. They claimed that unless they submitted to his orders, they were dismissed at once. He had decreased their wages by more than one half, made them pay for their places again, and demanded bonds from them that they should not disclose any of these things.2

2 Hist. MSS. Com., Rep., 7, p. 140.

In 1663, Bishop resigned his grant to Daniel O'Neale for £8,000. O'Neale offered £2,000 and, in addition, promised £1,000 a year, during the lease, to Henry Bennet, Secretary of State, if he would have the assignment confirmed. He promised this would not hurt the Duke of York's interest, who could expect no increase until the expiration of the original contract, which had over 4 years to run.3

3 Cal. S. P. D., 1663-64, p. 122; Rep. Com., 1844, xiv, app., pp. 86, 91 (60, 64).

This refers to an act of Parliament which had just been passed, settling the £21,500 post revenue upon James, Duke of York and his male heirs,4 with the exception of some £5,000 which had been assigned by Charles II to his mistresses and favorites.

4 Ibid., 1844, xiv, app., p. 91 (64). Confirmed in 1685 (Hist. MSS. Com., Rep., 11, app., 2, p. 315; 1 Jas. ii, c. 12).

O'Neale died before his lease expired, so his wife, Lady Katherine Wotton Stanhope van der Kerckhove O'Neill, Countess of Chesterfield, filled in until 1667.

San Diego Sarah • Link

Part 2